Legal considerations

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have become increasingly popular more recently. Starting with small blockchain games such as Crypto Kitties in 2017, they have entered public awareness with NBA Top Shot and the Christie’s auction raising USD 70 million for a digital art piece.

Given the recent success and increasing interest of mainstream media, it is time to take a closer look the mechanics and legal classification of NFTs. In many cases it is still unclear what NFTs legally represent, and poor technical implementation may render them worthless despite the buyer spending millions of dollars.

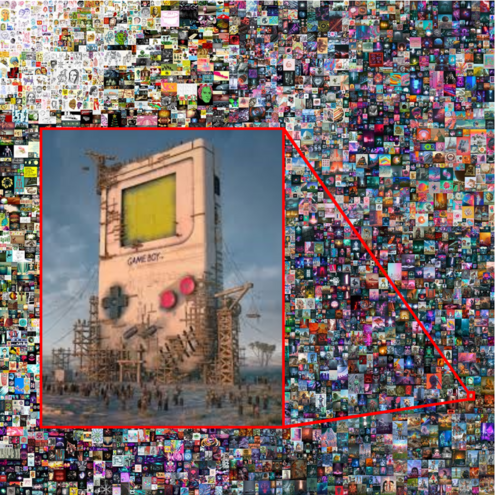

NFTs are commonly said to represent something unique. It may therefore come as a surprise that the content represented by the NFT can often be downloaded by anyone and duplicated freely. Take ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ which was auctioned off by Christie’s recently. While you cannot simply download the high-resolution picture from Christie’s website directly, it is recorded on the Inter Planetary File System (IPFS) where it can be accessed and downloaded by anyone. The file stored on IPFS is the same file the buyer of the digital artwork will eventually receive.

Beeple (b. 1981), Everydays: The First 5000 Days – Sold for USD 69,346,250 by Christie’s

The high-resolution file is recorded on IPFS and can be accessed and downloaded by anyone. The size file is 326MB. It might therefore take some time to download.

So, if the content is not unique, what is it, then? In fact, it is the token itself. NFTs, unlike other tokens, are not interchangeable. Each NFT has unique features and given these features, a different economic value. While you can easily interchange ten ERC-20 tokens with ten ERC-20 tokens of the same kind, you cannot do this with NFTs as you will end up with tokens that have different features and a different economic value.

Implemented properly, NFTs inextricably link to the content which they represent. Depending on the design, they may represent digital ownership or some other rights and make the otherwise easily duplicable content scarce.

Common use cases of NFTs include digital art, digital collectibles, in-game items and worlds, domain names, event tickets, and fan tokens. The focus of this post will be on digital art.

When dealing with NFTs it is important to understand why an NFT is unique, but more importantly, how it links to the content represented by it and where the content is stored.

On Ethereum, there are different token standards for NFTs – ERC-721 and ERC-1155. In the case of ERC-721, the NFT contains a mapping of unique identifiers with each identifier representing a single asset/content. In addition, it allows to track the owner of the token easily and creates a public trail of ownership. In the case of ERC-1155, the identifiers do not represent single assets but groups of assets. Tracking the provenance of single tokens is only possible if an ERC-721 superset is implemented. Given the possibility to track provenance, digital art typically uses the ERC-721 standard.

The metadata, which makes a token unique may either be on-chain or off-chain. Because of the costs for storing something on-chain, it is typically stored off-chain. In these cases, the NFT only contains a pointer to an external source which is typically an URL.

Once minted the data on the token becomes immutable and cannot be changed.[1] Depending on how the external content is stored the same is not necessarily true for the content. If the pointer in the NFT points to a URL that is controlled by a central entity or the artist himself, the artist may decide to replace the picture stored under the URL or to delete it completely. In addition, the link itself may be removed resulting in the NFT pointing to a 404 website.

Ultimately, this would leave the owner of the NFT in a very bad position as he still owns the NFT pointing to the URL where the digital art was originally stored. To draw attention to this issue, neitherconfirm replaced digital art with pictures showing rugs more recently.

To avoid this from happening and to ensure the data lives on forever, more recent projects including Beeple’s artwork on Christie’s use IPFS. Unlike current URLs, the IPFS creates unique URLs for files stored on the IPFS in a decentralized manner. If the file is changed, a new URL will be produced, meaning that the original file will always sit at the URL referenced in the NFT. Stated differently, the content and the token will become inextricably linked.

As important as the technical implementation is the question of what NFTs legally represent. This is important as it may limit what the creator or the buyer of an artwork can do, which again affects the price – both for primary and secondary sales. Other issues include the legal classification of NFTs under the Payment Services Act (PSA) and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA), their custody, and consumer protection laws.

Art, in general, involves a number of complex questions revolving around ownership and copyright. When creating an artwork, the creator generally becomes the first copyright owner. Registration at the copyright office is not necessary but may be advisable in some cases as it establishes a record of copyright ownership. For digital artworks, the same result can be achieved by signing the picture digitally, recording the corresponding NFT on the blockchain, and storing the high-resolution file on the IPFS.

But what does the NFT exactly represent? Digital ownership? Copyright? Or both?

This really depends on the artist as well as the platform the artist uses to sell his artworks. At an absolute minimum, an NFT represents digital ownership. The ownership of a digital artwork is transferred when transferring the NFT itself. The copyright, however, remains with the creator unless explicitly agreed otherwise.

As the first copyright owner, the artist has the exclusive right to make copies, sell and distribute the copies, prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted artworks and publicly display the artworks. In case you have been wondering how it is possible that some of the pictures in Beeple’s ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’had been sold in other auctions before but are still shown in his latest piece – this is the reason.

The copyright gives creators the following rights/protection:

Compared to copyright, ownership rights are rather limited and, broadly speaking, restricted to non-commercial use.

If a creator wants to grant the owner the right to use the artwork for commercial purposes (merchandize, display, etc.), he may either transfer the copyright or grant the owner a license to use the artwork commercially.

It should be noted that some platforms require creators to give the platform a license to use the artwork for commercial and non-commercial purposes. In the case of Open Sea, for example, the creator grants the platform a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to use the uploaded artworks for non-commercial and commercial purposes.

| “By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed). This license authorizes us to make your Content available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same. You agree that this license includes the right for OpenSea to provide, promote, and improve the Services and to make Content submitted to or through the Services available to other companies, organizations or individuals for the distribution, promotion or publication of such Content on other media and services. Such additional uses by OpenSea, or other companies, organizations or individuals, may be made with no compensation paid to you with respect to the Content that you submit, post, transmit or otherwise make available through the Services.” OpenSea, Section 9 Terms of Service |

When selling digital artworks to users, the creator must therefore consider which rights he has already granted to the platform to avoid potential conflicts. If a creator has given the platform a non-exclusive license to use the artwork for commercial purposes, he cannot grant an exclusive license to the buyer anymore.

Hashmasks clearly distinguished between ownership and copyright as well. In its terms and conditions, Hashmasks states that the buyer of the NFT does not only become the owner of the artworks but also that he is granted an unlimited worldwide, exclusive license to use, copy and display the purchased art.

| “You Own the NFT. Each Hashmask is a NFT on the Ethereum blockchain. When you purchase a NFT, you own the underlying Hashmask, the Art, completely. Ownership of the NFT is mediated entirely by the Smart Contract and the Ethereum Network”Hashmask, Section 3.A.i. of the Terms and Conditions |

| “Subject to your continued compliance with these Terms, The Company grants you an unlimited, worldwide, exclusive, license to use, copy, and display the purchased Art for the purpose of creating derivative works based upon the Art (“Commercial Use”). Examples of such Commercial Use would e.g. be the use of the Art to produce and sell merchandise products (T-Shirts etc.) displaying copies of the Art.” Hashmask, Section 3.A.iii. of the Terms and Conditions |

Even where the creator and the buyer explicitly agree on the transfer of the copyright or the granting of a license, the token does not necessarily reflect the exact terms. Written in natural language, the terms do not become part of the code. To ensure that all parties are always fully aware of the rights represented by the NFT, it is advisable that the NFT points to the respective terms and to store the terms on the IPFS. In this case, the NFT would not only serve as a track record of ownership but also bring more clarity with respect to the rights represented by it.

Crypto regulations and custody

According to the Japanese Financial Services Agency (FSA), NFTs are generally not considered securities or crypto assets. Trading, intermediary services for the trading, as well as the provision of custody services is therefore not regulated and may be performed without a license.

If a platform accepts BTC, ETH, or some other crypto asset as payment and manages the funds on behalf of the artist, the platform would however have to register as a crypto asset service provider with the FSA as it would engage in regulated activities – here the provision of custodian services.

BTC, ETH, etc. can be used for payment. There are no legal or regulatory limitations.

Consumer protection

Consumer protection laws only apply if the artist sells his artworks as a business. This must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Where the pictures are sold by a platform, consumer protection laws generally apply.

AML/CFT Regulations

Since art dealers are not regulated, they do not have to comply with AML/CFT regulations.

Tax

Gains from the sale of NFTs are classified as miscellaneous income under Japanese tax law. As such they are subject to a progressive tax rate of up to 45% plus a fixed local inhabitants’ tax of 10%.

[1] In many cases, it is still possible to change the metadata in the smart contract. It is therefore advisable to analyze each smart contract carefully.