In this post, we analyze non-fungible tokens (NFTs), play-to-earn scholarships, and the Yield Guild DAO under Japanese laws. With respect to the scholarships, it is worth noting that they are mainly offered overseas – presumably in compliance with the relevant laws – and that Japanese laws only apply if Japanese residents are involved. The following post is written under the assumption that this is the case.

| You can find more information about the legal and regulatory environment for NFTs in our previous posts: |

The P2E model was pioneered by Axie Infinity. Axie Infinity is an online game that allows players to receive rewards in the form of Smooth Love Potions (SLP) when playing the game. SLP are tokens that are needed for breeding new Axies and which can be traded on global crypto exchanges.

To play Axie Infinity, a player needs at least three Axies. In August 2021, the price for three Axies was around USD 1,000 and as such unaffordable for many players. Yet, despite the high costs, the game continued to gain popularity – especially in countries with low incomes. One of the reasons behind the continued success were scholarships. Under the scholarship program, owners of Axies give their Axies to players who in turn use them for playing the game. When earning SLP as rewards, players must share them with the owners of the NFTs. The percentage players retain is somewhere between 40 and 75 percent, depending on the provider of the scholarship and scholarship program.

Scholarship programs in a nutshell

|

Yield Guild Games (YGG) describes itself as a “play-to-earn gaming guild, bringing players together to earn via blockchain-based economies”. YGG initially raised funds from a16z and other investors in exchange for YGG tokens and invests those funds into NFTs that are used in blockchain games. Proceeds from utilizing the NFTs – for example from lending the NFTs to players of P2E games or selling them on the market – are distributed to YGG token holders.

In some cases, YGG further brokers scholarships for NFT holders who want to put their NFTs to use and earn a passive income. Initial activities focus on Axie Infinity, The Sandbox, and League of Kingdoms. Further games will be added in the future.

While the core team of YGG currently manages all activities, YGG aims to become fully decentralized in the future. Once the transition is completed, decision-making will be transferred from the core team to the YGG DAO, i.e. the YGG token holders.

Scholars and managers enter into scholarship agreements on an individual basis. Usually, the agreements are initiated via Discord or other channels. Under Japanese laws, the following structures may be considered.

Where a scholar promises to pay a certain amount of money for the use of Axies and to return the Axies at the end of the agreement to the manager, the agreement might be considered some form of lease. Since Article 601 Civil Code only covers the lease of tangible assets, it cannot be applied directly to the lease of intangible assets such as Axies. Applying Article 601 ff Civil Code by way of analogy seems, however, possible.

Assuming Articles 601 ff Civil Code can be applied analogously, scholars would not be allowed to sublease Axies to third parties without the prior consent of the managers (Article 612(1) Civil Code). In cases where the contract period is not specified by the scholarship agreement, the agreement may be terminated by either party by giving the other party one day’s notice (Article 617(1)(iii) Civil Code). As it is not clear whether courts will allow for an analogous application of Articles 601 ff Civil Code, it is advisable to cover all matters comprehensively in the scholarship agreement.

Since the use of Axies is not subject to restrictions under the Copyright Act, it is further advisable to implement proper measures to ensure that owners are sufficiently protected (e.g. prohibition to use Axies for breeding, prohibition to create merchandise with the Axie).

Managers may among others specify how many hours a scholar must play per month, require daily logins, or instruct scholars to only use Axies with certain characteristics for breeding. In addition, the scholarship agreement may stipulate a minimum amount of SLP a scholar must earn during a pre-defined period. In exchange, the manager agrees to pay a remuneration to the scholar.

Depending on the exact arrangement, the scholarship agreement may either be considered a contract for work (Article 632 Civil Code) or delegation without legal authority (Article 656 Civil Code). In both cases, scholars would have to deliver earned SLP to the NFT’s owner (Articles 632 and 646 Civil Code. Where the scholarship agreement is structured as a contract for work, NFT owners may further require scholars to complete the agreed work (Articles 559 and 562 Civil Code).

It is our understanding that the rewards collected by scholars are generally passed to the manager. Based on the scholarship agreement, the manager will then return a predefined amount to the scholar for playing the game. The situation is, therefore, similar to revenues generated by tenants of farmland.

The scholarship arrangement may further be structured as a partnership according to Article 667 Civil Code or a silent partnership according to Article 535 Commercial Code. In these cases, both the owners of the NFT and the scholar make contributions in kind – the owner by providing his Axies and the scholar by contributing his labor. Profits generated by the partnership or silent partnership are then distributed between NFT owners and scholars according to the scholarship agreement.

In a partnership, the owner may for example invest Axies and appoint the scholar as an executive of the partnership (Article 670(2) Civil Code). Here, the NFT owner would have the right to inspect the scholar’s business but lose the right to manage the partnership on his own (Article 673 Civil Code). If the scholar does not play the game and defaults, the agreement cannot be canceled (Article 667-2(2) Civil Code). Instead, the manager may request the dissolution of the partnership (Article 683 Civil Code). A voluntary resignation from the managing position by the scholar appointed as the manager of the partnership would only be possible if the scholar has a valid reason for resignation (Article 672(1) Civil Code).

| NFT Owners’ Rights and Obligations | Scholars’ Rights and Obligations | Other | |

| Lease |

|

| If the term is stipulated in the scholarship agreement, the agreement is automatically terminated with its expiration. Otherwise, it can be terminated by either party by giving one day’s notice. |

| Delegation / Contract for Work |

|

| The agreement may automatically terminate upon expiration of the term (if specified) or can be canceled by the manager at any time. If the manager decides to cancel the agreement which constitutes a contract for work, he must generally compensate the scholar for losses. If the agreement constitutes a delegation agreement, it may be terminated at any time by either party. |

| Fund |

|

| If the partnership has achieved the purpose for which it was set up, it is automatically dissolved. It is also dissolved if there are other reasons for dissolution which are stipulated in the scholarship agreement. Proceeds are distributed in proportion to each partners’ contribution in case of liquidation. |

The regulatory considerations vary greatly depending on the legal structure of the scholarships. For scholarships structured as leasing arrangements, money lending regulations may be considered. For agreements structured as partnerships or silent partnerships, the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) may be applicable. For scholarship structured as delegation agreements or contracts for work, no particular regulations apply.

Article 2(1) Money Lending Business Act defines money lending business as the business of lending money (including the provision of funds by discounted bills, the sale of mortgages, or similar methods) or acting as an intermediary for the lending of money. Businesses engaging in money lending services must register with the Financial Services Agency (FSA) (Article 3(1) Money Lending Act).

Since Axies neither constitute money nor a currency-denominated asset, the lending of Axies does not fall under the Money Lending Business Act. It is therefore not necessary to register with the FSA.

The FIEA applies to a wide range of financial instruments and provides a comprehensive registration regime for businesses engaging in financial instruments services (Article 2(8) FIEA). According to Article 29 FIEA, businesses providing financial instruments services must generally register as a financial instruments business operator (FIBO) with the FSA. This also applies to those soliciting the offer to sell rights in a partnership or silent partnership. Both are generally considered collective investment schemes under the FIEA (Article 2(2)(v) FIEA).

Axies do, however, not fall under the category of money or money equivalent as specified in Article 2(2)(v) FIEA, Article 1-3 FIEA Enforcement Order, and Article 5 FIEA Definitions Ordinance. Even where the owner of NFTs contributes his NFTs to the partnership or the silent partnership, the FIEA does therefore not apply.

Since NFTs do not constitute money or currency-denominated assets (see item 2.2.1 above), the brokerage of scholarships does not constitute an intermediary service for money lending and is therefore not regulated.

On August 19, 2021, YGG announced that it had raised USD 4.6 million from a16z and other major venture capital firms. In exchange for their investment a16z and the other investors received YGG tokens. The tokens allow them to participate in the revenues generated by the YGG. Assuming the tokens were sold to investors in Japan, it is highly likely that they would qualify as rights in a collective investment scheme under Article 2(2)(v) FIEA – and given the tokenization of those rights – as electronically recorded transfer rights (Article 2(3) FIEA). In order to offer electronically recorded transfer rights to the public, it is generally necessary to file a prospectus and to register as a type II FIBO (Articles 28(2)(i), 2(8)(vii), 29 FIEA). Where the rights are only offered to qualified institutional investors a notification under Article 63 FIEA is sufficient.

If the solicitation is, however, performed by a DAO with a sufficient degree of decentralization, the solicitation falls outside the scope of the FIEA as there is no eligible intermediary that could be regulated. As YGG is still managed by the core team, this degree of decentralization has most likely not been achieved yet.

Finally, it should be noted that collective investing schemes investing in NFTs are not subject to disclosure obligations under Article 4 FIEA, as NFTs do not constitute securities.

A fund investing exclusively in NFTs does not invest “in securities or in rights connected with derivatives transactions, based on investment decisions that are grounded in an analysis of values of financial instruments” as stipulated in Article 2(8)(xii) FIEA. It is therefore unlikely that the investment management regulations apply to the investment manager (Article 28(4)(i) FIEA).

As NFTs are further not considered crypto assets within the meaning of Article 2(7) Payment Services Act, the buying and selling of NFTs for investment purposes does not constitute a crypto asset exchange business. It is therefore not necessary to register as a crypto asset exchange service provider.

Disclaimer

This post is for discussion only. The content of this post has not been confirmed by the relevant authorities or organizations mentioned in the post but merely reflects a reasonable interpretation of their statements. The interpretation of the laws and regulations reflects our current understanding and may therefore change in the future.

This post does not recommend the use of or investment in NFTs, scholarships, or any other tokens or projects.

Axie Infinity and Yield Guild Games are only used for illustrative purposes. Given the format of the post, not all details of the game mechanics and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator, or a legal opinion prepared by us or another law firm. By no means, the explanations should be understood as a legal opinion. If you need legal advice on a similar project, please free to contact us or consult with your lawyer.

Axie Infinity, the blockchain game by Sky Mavis, made major headlines recently. With more than 350,000 daily active players, the game is one of the most successful blockchain games so far. According to data from token terminal_, the game generated USD 581.7 million in revenue over the past 90 days. To put this into perspective, this is more than Ethereum over the same period of time.

So, what is behind the success of Axie Infinity?

Part of it can be attributed to the active Axie community and the cute pets – called Axies – that are used for battles. The other part is the new ‘Play-to-Earn’ gaming model. This model allows players to earn ‘real’ money by playing the game. Depending on the token price, the rewards are said to be somewhere between USD 300-500 per month. With the latest increase of AXS, they might be even higher.

To understand how the ‘Play-to-Earn’ model works, it is necessary to take a closer look at the game and the tokens involved.

There are basically three types of tokens in the game.

To play the game players need at least three Axies. The Axies can be bought on the marketplace and currently cost around USD 200 or more.

To breed new Axies, players need 4 AXS and a certain number of SLP. To control the Axie population, it becomes increasingly expensive to breed Axies with same parents. After being used for breeding 7 times, Axies become sterile and cannot be used for further breeding.

| breed count | breed number | SLP cost |

| (0/7) | 1 | 150 |

| (1/7) | 2 | 300 |

| (2/7) | 3 | 450 |

| (3/7) | 4 | 750 |

| (4/7) | 5 | 1200 |

| (5/7) | 6 | 1950 |

| (6/7) | 7 | 3150 |

As all assets in the game are represented by NFTs and all rewards are paid in AXS or SLP, there are different ways for players to earn income:

» farming SLP and AXS by playing quests or battling other players

» participating in tournaments

» breeding new Axies and selling them on the marketplace

» speculating on rare Axies

In the future, it will also be possible to use AXS for staking. Staked AXS will allow token holders to earn additional AXS from the staking and treasury pool.

Now that we know the basic gaming mechanics and the functions of each token, it is time to get a better understanding of the legal and regulatory environment in Japan. As the results of the analysis vary considerably, it is necessary to assess each activity and token individually.

Farming of AXS/SLP: The farming of SLP and AXS by playing quests or battling other players is generally subject to the limitations under the Improper Premiums and Misleading Representations Act (IPMR). The IPMR provides limits for items and other assets that can be given away for ‘free’. In the case of play-to-earn models where players must make an initial investment to play the game, the amount that can be given away for free is limited to JPY 100,000 or 2 percent of the initial sales, whichever is higher, or – for initial investments below JPY 5,000 up to 20 times the price of the initial investment.

Gambling laws do generally not apply as users are not required to pay any fees to qualify for the rewards. The fact that users must purchase three Axies to play the game is irrelevant as the purchase is neither directly nor indirectly linked to the rewards earned by playing quests or battling other players.

As users are not required to pay any fees or other consideration – time and effort spent for playing the game are not considered – there is no purchase or exchange of crypto assets. Crypto asset regulations do therefore not apply to the issuance of AXS and SLP.

Tournaments: Where players are required to pay a fee to participate in a tournament and win rewards, there is a high chance that both the organization of the tournament and the participation in the tournament is considered illegal gambling. Something different only applies where the fees are only used to cover the expenses of the organizer. The expenses may include prizes for the winning players or teams.

Breeding of Axies: Since a user must pay a certain amount of SLP to breed new randomly generated Axies, there is a possibility that the breeding of new Axies is considered illegal gambling.

Selling Axies: When selling items combined with the promise of future returns, companies must comply with the Specified Commercial Transaction Act. Under the act, companies must not engage in certain advertising efforts and must disclose specific information, including the company’s name, to prospects. Given the ambiguous wording of the act, it is uncertain whether it applies to the sale of Axies by Sky Mavis. For sales by users, the act is irrelevant.

Selling AXS, SLP, NFTs by Users: The sale of AXS, SLP, and NFTs by the user is not regulated under Japanese laws.

Marketplace for AXS, SLP, NFTs: AXS and SLP are considered crypto assets under Japanese laws. Anyone who offers a marketplace for the exchange of AXS and SLP would therefore generally have to register as a crypto asset exchange. The same would apply to custodial wallets that manage the private keys controlling the users’ AXS and SLP.

NFT marketplaces for Axies, items, and lands are not regulated in Japan.

DISCLAIMER

The play-to-earn mechanism of Axie Infinity is only used for illustrative purposes. Given the format of the article, not all details of the game mechanics and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator, or a legal opinion prepared by us or another law firm. By no means, should the explanations be understood as a legal opinion.

Capital and financial markets regulation is based on the principle ‘same business, same risks, same regulation’. At the same time, global standard setters and national regulators alike consistently highlight that regulations are meant to be technology-neutral.

So, what happens if the technology changes the risk profile of a business?

The risk profile is redefined.

In a blockchain context, this seems to be one-directional, however. Rather than considering the full transparency and auditability of permissionless blockchains when assessing the risk profile, the FATF and national regulators do not get tired of stressing the risks related to pseudonymity and peer-to-peer transactions. The fact that blockchain analytics companies can track every transaction on most major networks is only considered as part of the risk mitigation measures.

By then, the risk profile is already established and may cause financial institutions and other regulated entities to refrain from interacting with the blockchain space altogether.

If technology changes the risk profile, it should apply in both directions.

On March 19, 2021, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) announced that it is updating its guidance for a risk-based approach to virtual assets and virtual asset service providers. The update is open for comments until April 20, 2021, and, if implemented as is, will have far-reaching implications for the DeFi space.

The updates include the following areas and are meant to provide the public and private sector with more clarity:

The focus of this post will be on item 1. The other areas will be covered in a separate post in the future.

| “A virtual asset is a digital representation of value that can be digitally traded, or transferred, and can be used for payment or investment purposes. Virtual assets do not include digital representations of fiat currencies, securities and other financial assets that are already covered elsewhere in the FATF Recommendations.” Source: Glossary of the FATF Recommendations |

In the updated guidance, the FATF highlights that no asset should entirely fall outside the FATF standards. At the same time, no asset should be considered both a VA and a traditional financial asset. In cases where it is difficult to characterize an asset as a VA or a traditional financial asset, jurisdictions are required to decide which designation suits best to mitigate and manage the risk of the product.

So what is a VA according to the FATF?

A VA is not a traditional financial asset. The digital representation of fiat currencies, securities or other financial assets are therefore not covered by the definition. For an asset to be considered a VA, the asset must further be digitally traded or transferred and used for payment or investment purposes. The otherwise denied inherent value of cryptocurrencies is seen as a defining feature of VA.

While it is easy to see that cryptocurrencies, utility tokens and governance tokens are covered by the definition it is not clear whether non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are included as well. Given the fact that they have a similar risk profile with respect to cross-border transfers, their increasing popularity, and pseudonymity, it is however likely that the FATF wants to see these assets covered by the definition as well.

| “Assets should not be deemed uncovered by the FATF Recommendations because of the format in which they are offered and no asset should be interpreted as falling entirely outside the FATF Standards.“ Source: Draft updated Guidance for a risk-based approach to virtual assets and VASPs, para 40 |

To include NFTs representing digital art, collectibles or in-game items would however constitute a departure from the principle of financial markets regulation. After all other unique assets such as traditional arts, real estate, etc. are not covered by the definition of traditional financial assets as well which are fungible by definition – or in other words interchangeable with each other.

| “Virtual asset service provider means any natural or legal person who is not covered elsewhere under the Recommendations, and as a business conducts one or more of the following activities or operations for or on behalf of another natural or legal person: i. exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies; ii. exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets; iii. transfer of virtual assets; iv. safekeeping and/or administration of virtual assets or instruments enabling control over virtual assets; and v. participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset.” Source: Glossary of the FATF Recommendations |

As with the definition of VA, the FATF highlights that the definition of VASP must be interpreted broadly. Without going into the details of what services are covered by item (i) to (iv), the focus of this post is on the question to which extent DeFi protocols are covered. The updated guidance provides more clarity on this which does, however, not necessarily mean that you will like it.

In short, it can be summarized as follows:

Software developers do not fall under the definition of VASP. But – according to the FATF there are hardly any cases where someone only provides a software solution.

So, let’s look at this in some more detail.

In the guidance, the FATF reiterates that it does not intend to regulate technology. The target of regulation are always natural or legal persons – in other words, individuals and legal entities. This point is important as it allows projects to assess whether they fall within the scope of VASP and, where necessary, make changes to their setup. As can be seen from the following statement, this will become increasingly difficult – yet not impossible – in the future.

| “The FATF takes an expansive view of the definitions of VA and VASP and considers most arrangements currently in operation, even if they self-categorize as P2P platforms, may have at least some party involved at some stage of the product’s development and launch that constitutes a VASP. Automating a process that has been designed to provide covered services does not relieve the controlling party of obligations.” Source: Draft updated Guidance for a risk-based approach to virtual assets and VASPs, para 75 |

According to the FATF, the expansive view is a conscious choice. Despite its commitment to innovation and not regulating software developers, this could still be the ultimate result. Similar to blockchain companies that were not meant to be excluded from traditional finance on a wholesale basis but still have a hard time opening bank accounts, the regulation of software developers might just be another collateral damage, and as such a conscious choice by the FATF.

So, if the regulatory environment was as strict as we claim here, how is it possible that projects like Uniswap allow users to exchange millions worth of dollars daily without being regulated?

First, the new guidance has not been finalized yet.

Second, the guidance has not been implemented into national law yet.

Third, even if it was implemented as is, law enforcement is still a different issue altogether.

The fact that the FATF intends to update its guidance on VAs and VASPs shows that the success of DeFi has not gone unnoticed. From the request for public comments, it is also clear that the overall direction is set – more regulation rather than less. The request only aims at removing potential ambiguities that could give countries room for interpretation and offer loopholes for DeFi projects and other innovations.

Getting back to Uniswap which was initially funded by venture capital, there is indeed the risk that it falls under the definition of VASP. The fact that the governance of Uniswap was largely distributed to the community by an airdrop last year, does not necessarily lead to a different result if other elements of the VASP definition remain in place.

Where the initiators of a protocol, for example, control the admin keys of the exchange’s smart contracts, the initiators may be considered a VASP. If transaction fees, on the other hand, are not distributed to the initiators of the protocol but the liquidity providers, this may lead to different results as the VASP – if existent – is not provided as a business.

Since there is no bright line test, there is always the possibility that DeFi protocols or the teams behind them are considered VASP. As the FATF wants its recommendations to be as broad as possible, it is highly likely that the teams behind DeFi protocols will initially be considered VASP unless active measures are taken, and proper structures implemented are implemented to further mitigate this risk.

The updated guidance shows that the FATF has been monitoring the DeFi space closely. If implemented as is, most projects will be covered as VASP under the new guidance. The growing regulatory burden has the potential to slow down innovation in the DeFi space. More likely than not, the industry will however find an appropriate answer which either includes increasing decentralization or the implementation of new solutions such as DeFi Compli from CipherTrace.

Besides all the criticism, the new regulations should also be considered as an opportunity for CeFi as it will most likely allow registered exchanges to implement DeFi solutions much more easily.

In 2019, Andreessen Horowitz predicted that in the not-too-distant future every company will be a FinTech company. Fast-forward to today, and most large companies embed financial services into their products to streamline the customer journey and increase their lifetime value.

Embedded finance typically covers the following services:

Generally speaking, there are three different types of entities involved in embedded finance – brands, enablers, and license holders.

| Brands | Non-financial services companies that embed financial services into their platforms and applications to improve the user experience and increase their lifetime value. |

| Enablers | Companies acting as the middle layer between brands and license holders. |

| License Holders | Financial services companies that are registered with or licensed by the Financial Services Agency (FSA) |

Historically, enablers and license holders have been largely identical in Japan. Yet, there is no particular reason why this should not change. In particular, the amended Act on the Provision of Financial Services is likely to bring new momentum to the FinTech industry as it allows financial intermediaries to provide services across different sectors with a single registration.

For brands the upcoming changes mean that they will be able to embed different types of financial services much easier, which in turn will drive demand for enablers connecting them smoothly with different license holders.

The type of license depends on the kind of services the license holder intends to provide. In most cases one of the following licenses is required:

One example that might be different from other jurisdictions is to the provision of lending services in online shops. Depending on the type of lending services different licenses are needed. A careful analysis is therefore necessary.

If the license holder, for example, makes the payment on behalf of the buyer by granting an instalment loan, this is considered an ‘instalment sale’ which falls under the supervision of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. If the license holder, however, lends the money to the buyer, and the buyer uses that money to pay the shop, lending regulations apply, and the license holder falls under the supervision of the Financial Services Agency.

A brand only needs a license if it acts as an intermediary for financial services. ‘Intermediation’ under Japanese laws is understood broadly and covers any act that furthers the execution of financial contracts. If a brand’s application, for example, seamlessly integrates financial products, this is generally considered an intermediation of financial services.

On the contrary, the introduction of financial products does generally not require a license. If a user is forwarded to the license holder’s website to purchase financial products, for example, the brand is not regulated.

Until this year, the intermediation of different kinds of financial services required different licenses. The intermediation of banking services required a banking agent license, the intermediation of securities services required an intermediation of financial instrument license and so on. For the intermediation of different types of financial products, the brand therefore needed different licenses. From mid of this year, this will change however, and a single license will be sufficient.

If an enabler provides intermediary service as described in the previous section, it has to apply for an intermediation license.

If an enabler, however, only provides a software solution connecting the brand with the license holder a license is not required.

Depending on the exact service, companies may or may not be subject to license requirements in Japan. At a very high level the regulatory environment is as follows:

A more detailed overview can be found in the following section.

As mentioned above, the license requirements differ considerably depending on what kind of service is carried out. A careful case-by-case analysis is therefore necessary.

Instruction by brand

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | brand instructs user’s bank to transmit money to brand’s account for purchasing goods or services | provides API for instruction | money transfer |

| applicable laws | not regulated | not regulated | Banking Act (BA) or Payment Services Act (PSA) |

| license/registration requirement | not regulated | not regulated | banking license under BA or money transmitter license under PSA |

Instruction by third party

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | – | instructs user’s bank to transmit money to brand’s account | money transfer |

| applicable laws | – | BA or not regulated | BA or PSA |

| license/registration requirement | – | registration as electronic payment services provider under BA if instruction is given to bank not regulated if instruction is given to money transmitter | banking license under BA or money transmitter license under PSA |

Payment by third party (performance by user at the time enabler receives payment)

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | entrusting the collection of payment to the enabler | receiving payment from user and making payment to brand (performance by user under the agreement with brand at the time enabler receives payment) | – |

| applicable laws | – | not regulated | – |

| license/registration requirement | – | not regulated | – |

Money transmission (not related to the purchase of goods or services)

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | brand instructs user’s bank to transmit money to another person’s account | – | money transfer |

| applicable laws | BA or not regulated | – | BA or PSA |

| license/registration requirement | registration as electronic payment services provider under BA if instruction is given to bank not regulated if instruction is given to money transmitter. | – | banking license under BA or money transmitter license under PSA |

Inhouse instalments

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | brand provides installment loan to user to finance purchases | – | – |

| applicable laws | Installment Sales Act | – | – |

| license/registration requirement | not regulated | – | – |

Credit purchase brokerage

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | brand intermediates advance payment and installment payment from license holders | – | license holder makes advance payments to brand and receives installment payments from user |

| applicable laws | not regulated- | – | Installment Sales Act |

| license/registration requirement | not regulated | – | registration as credit purchase brokerage business and in cases where the amount is less than JPY 100,000 registration as small-amount credit brokerage business |

Loan affiliated sales

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | brand intermediates loan and then jointly and severally guarantees the loan payment | – | license holder provides loan to user to finance purchase in brand’s online shop |

| applicable laws | Installment Sales Act, BA or Money Lending Business Act (MLBA) or Financial Services Act | – | BA or MLBA |

| license/registration requirement | brands must comply with some duties under the Installment Sales Act (no license/registration) intermediaries of loans must obtain a bank agency business license under BA or register as money lending business under the MLBA or as financial services intermediary under Financial Services Act | – | banking license under BA or registration as money lending business under MLBA |

Affiliated loan

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | provides access to loan products in its online store | – | license holders provides loan to user to finance purchase in brand’s online shop |

| applicable laws | BA or MLBA or Financial Services Act | – | BA or MLBA |

| license/registration requirement | intermediaries of loans must obtain a bank agency business license under BA or register as money lending business under the MLBA or as financial services intermediary under Financial Services Act | – | banking license under BA or registration as money lending business under MLBA |

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | provides interface for investments in securities through app | – | investment into securities |

| applicable laws | Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) | – | FIEA |

| license/registration requirement | if brand is a financial institution, it must be registered as a financial institution engaging in the investment advisory and agency business; it is not allowed to use a financial services intermediary under the FIEA if the brand is not a financial institution, it can act under the investment advisory business or as a financial instruments intermediary business under the FIEA or a financial services intermediary business under the Financial Services Act | – | investment business under the FIEA |

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | provides access to insurance products in its online store | – | provides insurance products |

| applicable laws | Insurance Business Act or Financial Services Act | – | Insurance Business Act |

| license/registration requirement | registration as insurance agent under Insurance Business Act or financial services intermediary under Financial Services Act | – | insurance business license or small insurance business license |

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | provision of withdrawals and deposits through the app | – | deposit |

| applicable laws | BA or Financial Services Act | – | BA |

| license/registration requirement | permission for banking agency business under BA or registration as financial services intermediary business under Financial Services Act | – | banking license |

Debit cards issued by large companies

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | issuance of debit cards linked to bank accounts | – | deposits |

| applicable laws | BA or Financial Services Act | – | BA |

| license/registration requirement | permission for banking agency business under BA or registration as financial services intermediary business under Financial Services Act | – | banking license |

Debit cards issued by money transmitters

| brand | enabler | license holder | |

| service provided | issuance debit cards linked to money transmitters | – | transfers |

| applicable laws | PSA | – | PSA |

| license/registration requirement | not regulated | – | registration as money transmitter under PSA |

EOD

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have become increasingly popular more recently. Starting with small blockchain games such as Crypto Kitties in 2017, they have entered public awareness with NBA Top Shot and the Christie’s auction raising USD 70 million for a digital art piece.

Given the recent success and increasing interest of mainstream media, it is time to take a closer look the mechanics and legal classification of NFTs. In many cases it is still unclear what NFTs legally represent, and poor technical implementation may render them worthless despite the buyer spending millions of dollars.

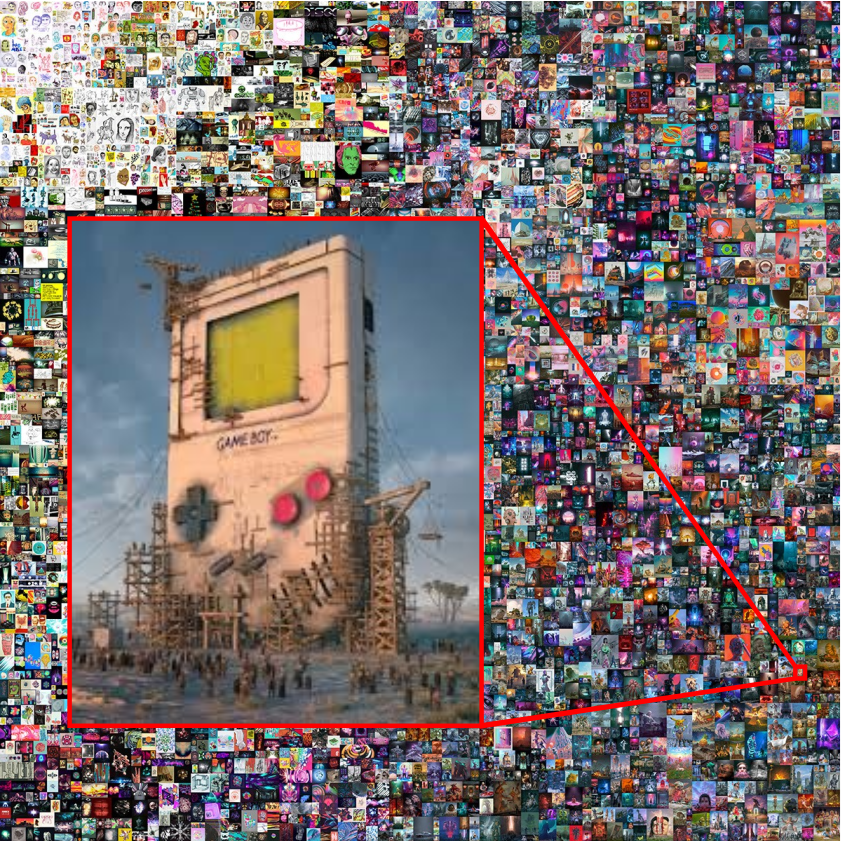

NFTs are commonly said to represent something unique. It may therefore come as a surprise that the content represented by the NFT can often be downloaded by anyone and duplicated freely. Take ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ which was auctioned off by Christie’s recently. While you cannot simply download the high-resolution picture from Christie’s website directly, it is recorded on the Inter Planetary File System (IPFS) where it can be accessed and downloaded by anyone. The file stored on IPFS is the same file the buyer of the digital artwork will eventually receive.

Beeple (b. 1981), Everydays: The First 5000 Days – Sold for USD 69,346,250 by Christie’s

The high-resolution file is recorded on IPFS and can be accessed and downloaded by anyone. The size file is 326MB. It might therefore take some time to download.

So, if the content is not unique, what is it, then? In fact, it is the token itself. NFTs, unlike other tokens, are not interchangeable. Each NFT has unique features and given these features, a different economic value. While you can easily interchange ten ERC-20 tokens with ten ERC-20 tokens of the same kind, you cannot do this with NFTs as you will end up with tokens that have different features and a different economic value.

Implemented properly, NFTs inextricably link to the content which they represent. Depending on the design, they may represent digital ownership or some other rights and make the otherwise easily duplicable content scarce.

Common use cases of NFTs include digital art, digital collectibles, in-game items and worlds, domain names, event tickets, and fan tokens. The focus of this post will be on digital art.

When dealing with NFTs it is important to understand why an NFT is unique, but more importantly, how it links to the content represented by it and where the content is stored.

On Ethereum, there are different token standards for NFTs – ERC-721 and ERC-1155. In the case of ERC-721, the NFT contains a mapping of unique identifiers with each identifier representing a single asset/content. In addition, it allows to track the owner of the token easily and creates a public trail of ownership. In the case of ERC-1155, the identifiers do not represent single assets but groups of assets. Tracking the provenance of single tokens is only possible if an ERC-721 superset is implemented. Given the possibility to track provenance, digital art typically uses the ERC-721 standard.

The metadata, which makes a token unique may either be on-chain or off-chain. Because of the costs for storing something on-chain, it is typically stored off-chain. In these cases, the NFT only contains a pointer to an external source which is typically an URL.

Once minted the data on the token becomes immutable and cannot be changed.[1] Depending on how the external content is stored the same is not necessarily true for the content. If the pointer in the NFT points to a URL that is controlled by a central entity or the artist himself, the artist may decide to replace the picture stored under the URL or to delete it completely. In addition, the link itself may be removed resulting in the NFT pointing to a 404 website.

Ultimately, this would leave the owner of the NFT in a very bad position as he still owns the NFT pointing to the URL where the digital art was originally stored. To draw attention to this issue, neitherconfirm replaced digital art with pictures showing rugs more recently.

To avoid this from happening and to ensure the data lives on forever, more recent projects including Beeple’s artwork on Christie’s use IPFS. Unlike current URLs, the IPFS creates unique URLs for files stored on the IPFS in a decentralized manner. If the file is changed, a new URL will be produced, meaning that the original file will always sit at the URL referenced in the NFT. Stated differently, the content and the token will become inextricably linked.

As important as the technical implementation is the question of what NFTs legally represent. This is important as it may limit what the creator or the buyer of an artwork can do, which again affects the price – both for primary and secondary sales. Other issues include the legal classification of NFTs under the Payment Services Act (PSA) and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA), their custody, and consumer protection laws.

Art, in general, involves a number of complex questions revolving around ownership and copyright. When creating an artwork, the creator generally becomes the first copyright owner. Registration at the copyright office is not necessary but may be advisable in some cases as it establishes a record of copyright ownership. For digital artworks, the same result can be achieved by signing the picture digitally, recording the corresponding NFT on the blockchain, and storing the high-resolution file on the IPFS.

But what does the NFT exactly represent? Digital ownership? Copyright? Or both?

This really depends on the artist as well as the platform the artist uses to sell his artworks. At an absolute minimum, an NFT represents digital ownership. The ownership of a digital artwork is transferred when transferring the NFT itself. The copyright, however, remains with the creator unless explicitly agreed otherwise.

As the first copyright owner, the artist has the exclusive right to make copies, sell and distribute the copies, prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted artworks and publicly display the artworks. In case you have been wondering how it is possible that some of the pictures in Beeple’s ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’had been sold in other auctions before but are still shown in his latest piece – this is the reason.

The copyright gives creators the following rights/protection:

Compared to copyright, ownership rights are rather limited and, broadly speaking, restricted to non-commercial use.

If a creator wants to grant the owner the right to use the artwork for commercial purposes (merchandize, display, etc.), he may either transfer the copyright or grant the owner a license to use the artwork commercially.

It should be noted that some platforms require creators to give the platform a license to use the artwork for commercial and non-commercial purposes. In the case of Open Sea, for example, the creator grants the platform a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to use the uploaded artworks for non-commercial and commercial purposes.

| “By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed). This license authorizes us to make your Content available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same. You agree that this license includes the right for OpenSea to provide, promote, and improve the Services and to make Content submitted to or through the Services available to other companies, organizations or individuals for the distribution, promotion or publication of such Content on other media and services. Such additional uses by OpenSea, or other companies, organizations or individuals, may be made with no compensation paid to you with respect to the Content that you submit, post, transmit or otherwise make available through the Services.” OpenSea, Section 9 Terms of Service |

When selling digital artworks to users, the creator must therefore consider which rights he has already granted to the platform to avoid potential conflicts. If a creator has given the platform a non-exclusive license to use the artwork for commercial purposes, he cannot grant an exclusive license to the buyer anymore.

Hashmasks clearly distinguished between ownership and copyright as well. In its terms and conditions, Hashmasks states that the buyer of the NFT does not only become the owner of the artworks but also that he is granted an unlimited worldwide, exclusive license to use, copy and display the purchased art.

| “You Own the NFT. Each Hashmask is a NFT on the Ethereum blockchain. When you purchase a NFT, you own the underlying Hashmask, the Art, completely. Ownership of the NFT is mediated entirely by the Smart Contract and the Ethereum Network”Hashmask, Section 3.A.i. of the Terms and Conditions |

| “Subject to your continued compliance with these Terms, The Company grants you an unlimited, worldwide, exclusive, license to use, copy, and display the purchased Art for the purpose of creating derivative works based upon the Art (“Commercial Use”). Examples of such Commercial Use would e.g. be the use of the Art to produce and sell merchandise products (T-Shirts etc.) displaying copies of the Art.” Hashmask, Section 3.A.iii. of the Terms and Conditions |

Even where the creator and the buyer explicitly agree on the transfer of the copyright or the granting of a license, the token does not necessarily reflect the exact terms. Written in natural language, the terms do not become part of the code. To ensure that all parties are always fully aware of the rights represented by the NFT, it is advisable that the NFT points to the respective terms and to store the terms on the IPFS. In this case, the NFT would not only serve as a track record of ownership but also bring more clarity with respect to the rights represented by it.

Crypto regulations and custody

According to the Japanese Financial Services Agency (FSA), NFTs are generally not considered securities or crypto assets. Trading, intermediary services for the trading, as well as the provision of custody services is therefore not regulated and may be performed without a license.

If a platform accepts BTC, ETH, or some other crypto asset as payment and manages the funds on behalf of the artist, the platform would however have to register as a crypto asset service provider with the FSA as it would engage in regulated activities – here the provision of custodian services.

BTC, ETH, etc. can be used for payment. There are no legal or regulatory limitations.

Consumer protection

Consumer protection laws only apply if the artist sells his artworks as a business. This must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Where the pictures are sold by a platform, consumer protection laws generally apply.

AML/CFT Regulations

Since art dealers are not regulated, they do not have to comply with AML/CFT regulations.

Tax

Gains from the sale of NFTs are classified as miscellaneous income under Japanese tax law. As such they are subject to a progressive tax rate of up to 45% plus a fixed local inhabitants’ tax of 10%.

[1] In many cases, it is still possible to change the metadata in the smart contract. It is therefore advisable to analyze each smart contract carefully.

It is one of the basic principles of capital and financial markets regulation that the same rules apply to the same business and the same risk. In the age of DeFi, this does not seem to be the case anymore. A second look shows, however, that nothing has changed but that the results have become far more difficult to predict.

To assess whether regulations apply, it is generally necessary to assess (1) whether the activities are regulated and (2) identify the entity/person engaging in such activities.

Until more recently, it has been relatively easy to identify both the regulated activities as well as the relevant actors. For DeFi protocols, the answer is not always that straight forward. In the absence of legal documents, it is often unclear how the services are structured (e.g. lending vs. investing). And even where it is possible to classify the respective activity, it is still necessary to analyze whether the activity is performed by a person (regulated) or a piece of software (unregulated).

This brings us to the question of when a project is sufficiently decentralized.

While there is no general answer to this question, there is a distinct set of factors that must be considered when answering the question. The most important factor is the degree of control the team retains over the project after it is launched. In many cases, the team retains admin rights to fix bugs or to upgrade the protocol. This alone may, however, not be enough to establish a sufficient link between the team and the regulated activity. In fact, a comparison with the traditional financial and capital markets shows that the regulations do not apply to the technology providers but those using the technology, in other words, banks, exchanges, and other financial intermediaries. Nasdaq, for example, is not only a registered exchange in the United States but also a software company providing its matching technology to more than 70 markets globally. This does, however, not make Nasdaq subject to regulations in all these markets. Instead, the regulated entities are those providing the marketplace.

If financial and capital markets regulations are meant to be interpreted technology-neutral as claimed by regulators around the globe, nothing different can apply to DeFi protocols. Just because the smart contracts are publicly available on the blockchain does not justify different results in the case of DeFi.

Something different applies, of course, if the team does not only develop and maintain the smart contract but also engages in the listing of tokens or provides the GUI for interacting with the protocol. In this case, there is a clear link between the regulated activity and the team, and registration becomes necessary.

If the GUI is provided by someone else, it is likely that this person becomes subject to regulation as this person opens the marketplace and facilitates trading, etc.

As can be seen from these examples, it is not always possible to draw a clear line. To avoid the risk of becoming subject to regulation, the best way is still full decentralization. In other words, the team must deploy smart contracts without admin rights or transfer the protocol’s governance to the community. While still untested, it is highly likely that this provides an effective shield against regulations.

The trade-off of this approach may, however, be a lack of institutional investment/usage. It is, therefore, necessary to consider the implications of a fully decentralized strategy holistically and not solely from a regulatory point of view. What works for one project might not necessarily be ideal for others.

We are proud to announce that So & Sato and Curvegrid are joining forces to deliver next-generation services at the intersection of finance, tech, and regulation.

With this first-of-its-kind partnership, we aim to address the key pain points that plague many businesses in the crypto industry and that have slowed down the development of the Japanese blockchain industry as a whole.

In many cases, these problems are of technical or legal nature. More often than not they are both. This adds further complexities to an already challenging environment which can neither be solved satisfactorily by law firms or tech companies on their own. Yet, many companies still follow this one-dimensional approach, which results in suboptimal solutions, delays, and wrong allocation of resources.

By combining the expertise of one of the leading law firms in the blockchain/crypto space with Curvegrid’s MultiBaas blockchain middleware and extensive technical knowhow, we are not only able to remove these inefficiencies but also to provide a one-stop solution for our clients, streamline communication with the regulators, assist with the launch of new products, and build solutions which are not only meeting the highest technical standards but which are also fully compliant.

Examples

Want to learn more? Feel free to contact us and arrange a meeting.

Curvegrid is a blockchain technology company based in Tokyo, Japan. Curvegrid’s MultiBaas blockchain middleware makes it fast, easy, and cost effective for companies to build on multiple blockchain platforms. Turnkey MultiBaas solutions are available for financial services, decentralized finance, online gaming, document management, logistics, and manufacturing that help companies get to market with blockchain faster than otherwise possible.

So & Sato is a boutique law firm specializing in blockchain and crypto. Our partners are fully bilingual and have worked with leading law firms in the US, Singapore, and Japan for many years. Our firm has been at the forefront of Blockchain and Fintech ever since it was established in 2015. In 2020, our partner So Saito was ranked among the top 3 FinTech lawyers in Japan by Chambers and Best Lawyers. Combining years of experience in the field of capital markets and finance with an in-depth understanding of new technologies, So & Sato is uniquely positioned to develop innovative solutions for our clients in a highly complex and constantly changing legal and regulatory environment.

Decentralized finance – more commonly known as DeFi – has gained increasing traction over the last few months. With new services and platforms being launched every week, the environment has become increasingly complex despite its short history.

This article provides an overview of the key building blocks of DeFi and the regulatory implications under Japanese laws.

KEY BUILDING BLOCKS OF DEFI

1. decentralized exchanges

2. automated market makers

3. lending platforms

4. aggregators

5. vaults

6. derivatives

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) provide users with a marketplace where they can buy and sell crypto assets. The basic concept of DEXes is similar to that of centralized exchanges. Stated differently, DEXes typically maintain order books and matching engines.

In some cases, both the order book and matching engine are on-chain, in other cases they are off-chain and only the settlement occurs on-chain.

Examples

From a regulatory perspective it is necessary to distinguish between the order book/order matching and the settlement.

Depending on the degree of decentralization, i.e. the degree a creator of a DEX can access the funds or control the smart contract via admin rights, activities may either be regulated or unregulated.

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

|

|

custodial |

non-custodial |

regulated |

|

off-chain order book |

+ |

yes |

|

|

+ |

yes |

||

|

on-chain order book controlled |

+ |

yes |

|

|

+ |

yes |

||

|

on-chain order book not controlled |

+ |

no |

|

|

+ |

yes |

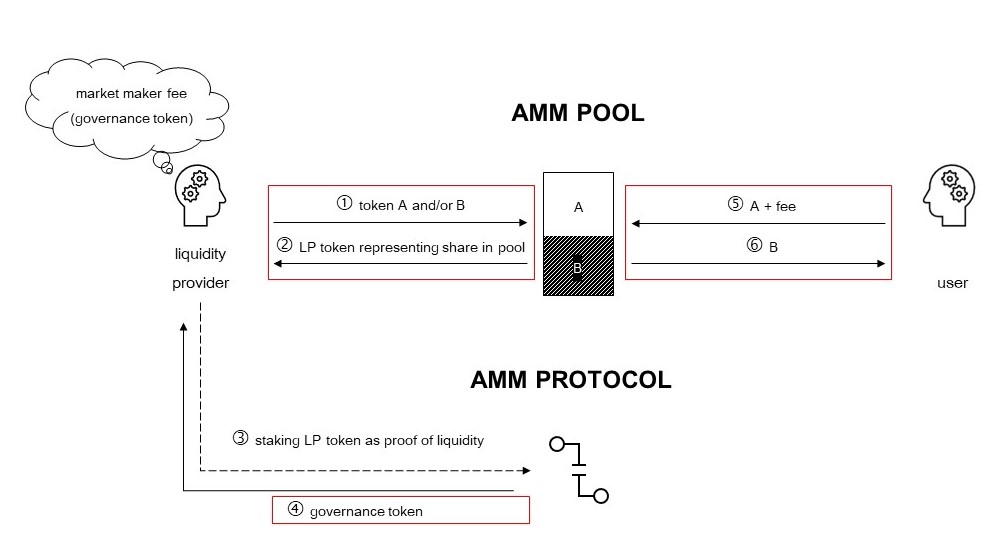

Automated Market Makers (AMMs) do not have order books. Instead they use liquidity pools that consist of at least one pair of crypto assets. The price of each crypto asset is measured against the other asset in the pool.

Uniswap for example uses the following formula to determine the price of each crypto asset in the pool:

x * y = k

In this equation, x and y represent the number of each token in the pool. While x and y vary over time, k remains constant and allows the AMM to determine the price of each asset at any point of time.

If a user exchanges ETH for DAI in an ETH/DAI pool, for example, the price of DAI becomes more expensive relative to ETH. This opens arbitrage opportunities if the ETH price in the pool deviates from the actual market price. To make use of the arbitrage opportunity a trader must only supply DAI to the pool and withdraw ETH. As a result, the price of ETH will be rebalanced and aligned with the overall market price.

The liquidity in the pools is provided by liquidity providers (LP). In exchange for providing liquidity LPs participate in the fees charged for interacting with the pool and in some cases receive a governance token as additional incentive.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

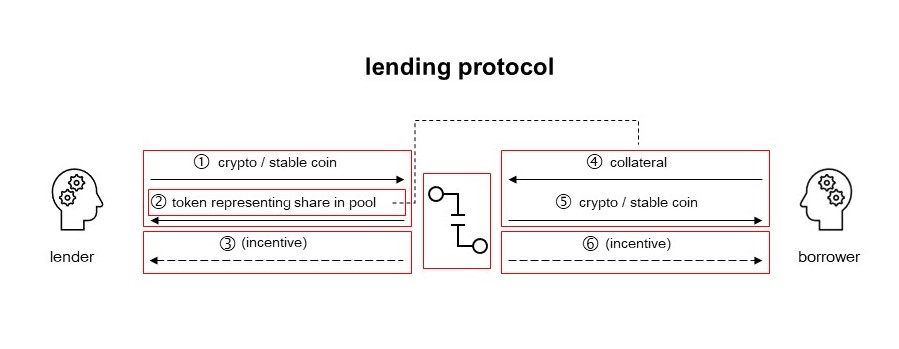

To borrow funds via one of the existing lending platforms, users must deposit crypto assets to the protocol. When supplying funds to the lending protocol, lenders receive a token representing their share in the lending pool. This token may be used as collateral when borrowing funds from the protocol.

Depending on the protocol, an additional token, typically in form of a governance token, may be issued to both the lender and borrower as an incentive to use the platform.

Borrowers pay interests to the protocol which either forwards them directly to the lender or releases them once the lender decides to unlock his funds from the protocol.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

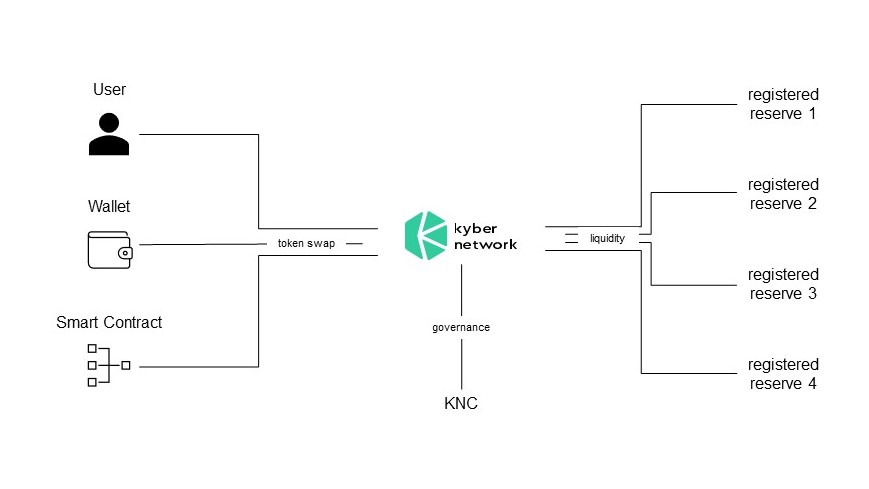

Aggregators connect users, wallets, and smart contracts with liquidity. By doing so, they allow them to swap tokens for the best price available across multiple platforms.

Other aggregators constantly look for the best yield and distribute the supplied funds accordingly.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

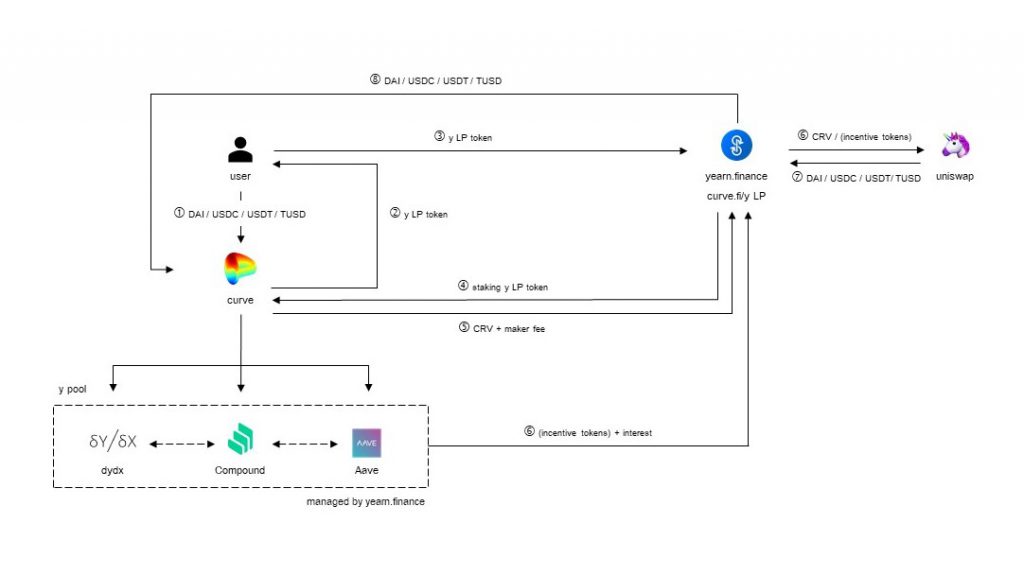

Vaults automatically optimize the returns on the funds supplied to them. To do so, they plug into multiple AMMs and lending protocols and move the funds wherever they generate the highest returns.

Where AMMs and lending protocols issue tokens as incentive, vaults automatically sell and reinvest them into the vault. One of the most prominent examples is yearn.finance.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

Derivatives platforms allow users to speculate and hedge their positions. For efficiency and cost reasons exchanges such as dydx use a hybrid off-chain/on-chain solution. The order book and order matching is performed off-chain while the margins paid by users of the platform are maintained by the protocol on-chain.

The infrastructure most derivatives exchanges operate on is similar to that of DEXes.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

DISCLAIMER

THIS DOCUMENT IS FOR GENERAL INFORMATION purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice; thus, it may not be relied upon regarding a specific legal issue or problem. The projects mentioned in this document are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the document not all details of the token design and underlying business model have been considered, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project.