Crypto derivatives have become increasingly popular and account for over 90 percent of the total trading volume in Japan. Internationally, crypto derivatives have gained increasing traction as well. Only in June, Deribit reported that BTC options on the exchange have reached a new all-time high with a total of USD 1.4 billion open interest. Almost at the same time, the daily exchange volume of CME bitcoin futures reached USD 1.3 billion.

The success of crypto derivatives has also caught much attention in the DeFi space. Projects such as dydx try to replicate the success of their peers while giving users more control over their funds.

Before diving into derivatives on dydx, namely perpetual futures, we will first explain how perpetuals work. In the second part, we will then analyze each step from the deposit of margins to the trading of derivatives in more detail.

Key Findings

| Derivatives exchange services | Crypto derivatives are financial instruments. A platform providing exchange services must therefore generally register as a type I financial instruments business operator. This may not apply for completely decentralized platforms without an operator. |

| Deposit of margin | Deposit-taking activities may be considered a crypto asset exchange service that must be registered with the FSA. This applies to both centralized and – depending on the functionality of the smart contract and admin rights – decentralized projects. |

| Derivatives transactions | Platforms themselves do generally not engage in crypto derivatives transactions directly. They do therefore not have to register as a financial instruments business operator with the FSA in respect to the trading activities. Despite providing liquidity on exchanges, users do generally not have to register with the FSA. In most cases, their activities are likely considered proprietary trading which is unregulated. |

One of the best ways to understand perpetuals is to look at forward contracts and standard futures first.

Forward contracts: Forward contracts are bilateral agreements according to which the parties trade a specified quantity of a particular good at a certain price at a predefined date in the future. The contract is typically negotiated between the parties and tailored to their needs. A unilateral transfer of rights and obligations is generally not possible.

Futures: Futures are similar to forward contracts in that they also concern the trade of a specified quantity of a particular good at a certain price at a predefined date in the future. Unlike forward contracts, futures are however highly standardized and traded on exchanges. For trades on the exchange, the exchange becomes the buyer to each seller and the seller to each buyer. The users of the exchange therefore only bear the counterparty risk of the exchange but not the default risk of the other party.

Perpetual contracts: Perpetual contracts – for the large part – are perpetual futures, i.e. futures without a maturity date. Often provided via offshore jurisdictions, they allow traders to get leveraged exposure to bitcoin or other crypto assets. Typically, the margin requirements are 1 percent of the contract value for the initial margin and 0.75 percent for the maintenance margin. Where the margin falls below the prescribed thresholds, the position is automatically liquidated by the exchange. In some cases, the position is completely liquidated at once. In other cases, the liquidation occurs incrementally.

To ensure that the price of perpetuals does not deviate too much from the index price of the underlying asset, perpetual contracts use a certain funding mechanism. Where the perpetual contract is traded above the index price of the underlying asset, the trader holding the long position must pay the difference to the trader holding the short position and vice versa. Funding payments are calculated in regular intervals. In some cases, these intervals only account for milliseconds.

Most exchanges maintain an insurance fund to cover losses from bankrupt traders. Only if the insurance fund is depleted, losses from bankrupt traders are socialized.

| Criterion | Collateral | Futures | Perpetuals |

| Buyer-seller interaction | Direct | Via exchange | Via exchange |

| Contract terms | Can be tailored | Standardized | Standardized |

| Unilateral reversal | Not possible | Possible | Possible |

| Default-risk borne by | Individual parties | Exchange | Individual parties |

| Default controlled by | Collateral | Margin accounts | Margin accounts and insurance fund |

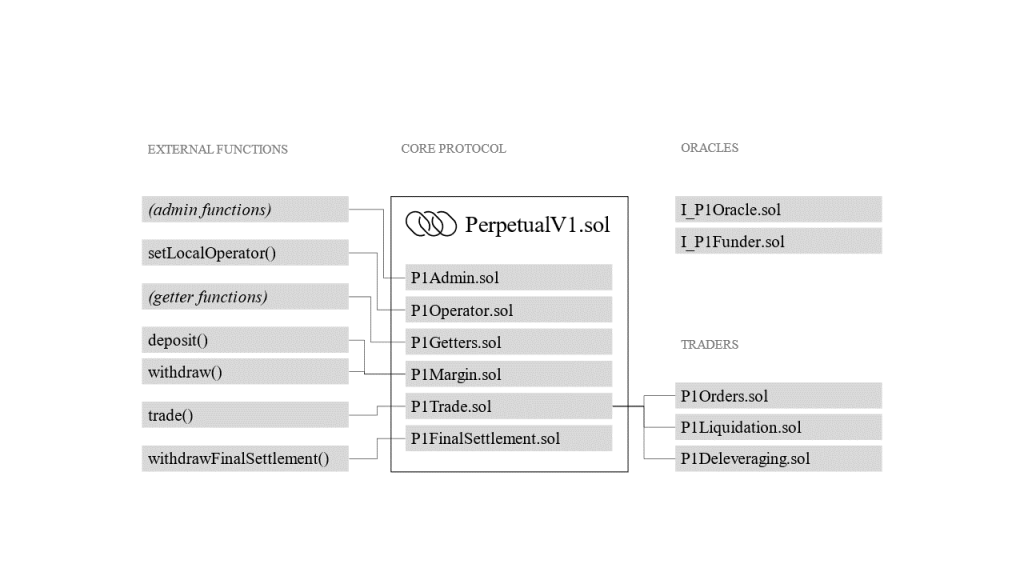

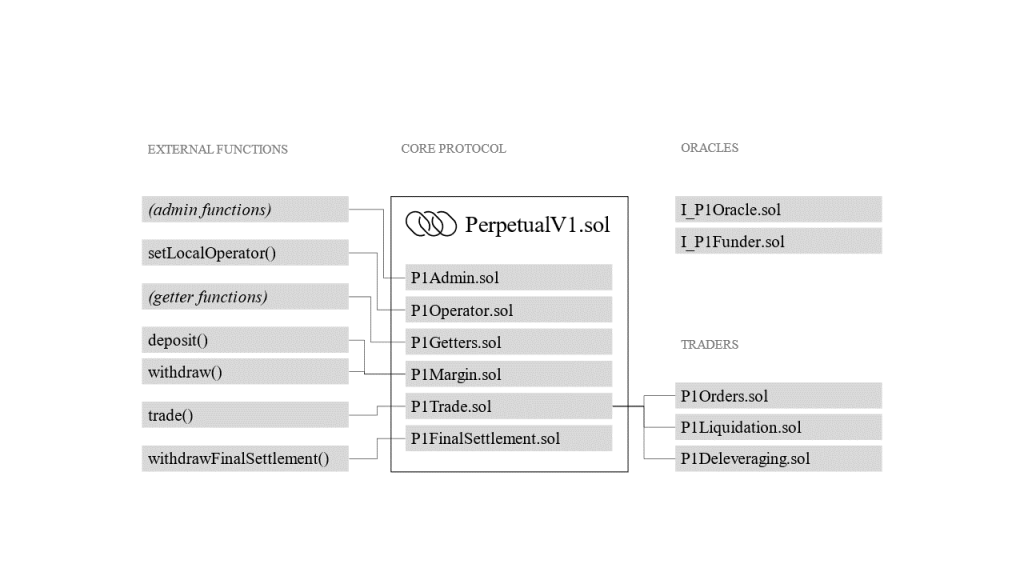

Perpetuals traded on dydx are not different from perpetuals traded elsewhere. Unlike other platforms dydx uses a different approach for the trading and settlement, however, by utilizing a hybrid on-chain/off-chain approach.

While the order book and the order matching is off-chain, all other actions are performed by smart contracts on-chain. These smart contracts are either developed by dydx or third parties (e.g. MakerDAO BTC-USD Oracle). Some of them have backdoors for administrators.

According to dydx, the hybrid solution is meant to combine the best of both worlds, i.e. off-chain speed and efficiency, and on-chain security.

In order to trade on dydx users have to pay a margin to dydx’s protocol. If the margin falls below the maintenance margin, an account may be liquidated. In the liquidation process anyone may assume the margin and position balances of the liquidated account, provided of course, he has sufficient margin on his own.

Where an account falls short and has a negative net value the admin of the perpetual smart contract or a third party can call an offsetting account to take over the balance. This account is typically the insurance fund maintained by dydx. If the insurance fund is depleted, the admin may determine another account with a high amount of profit and margin to take over the balance.

From a regulatory point of view, there are three different activities that must be assessed independently: (i) exchange services for derivatives, (ii) safekeeping of the margin, and (iii) engaging in derivatives transactions.

Crypto derivatives platforms are generally not considered financial instruments markets under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). Yet, it is still necessary to register as a type I financial instruments business operator (FIBO) when operating a platform. This also applies to entities that use hybrid solutions, i.e. an off-chain order book and matching engine combined with on-chain settlement. The hybrid solution of dydx, for example, would be subject to registration requirements.

Something different may apply where the order book and matching engine are on-chain and where there is no operator. The smart contracts should further not be controlled by the project’s developers. Projects that have originally controlled the entity but subsequently transferred control to the community may not be covered by the registration requirement anymore. Where the project team remains the majority owner of the governance tokens, it may still be seen as the operator of the platform. A careful analysis is therefore necessary.

Users who wish to trade perpetuals must generally deposit a margin. This applies to both centralized and decentralized platforms, whereas for the latter, the amount is not paid to the platform, but a smart contract deployed by the platform.

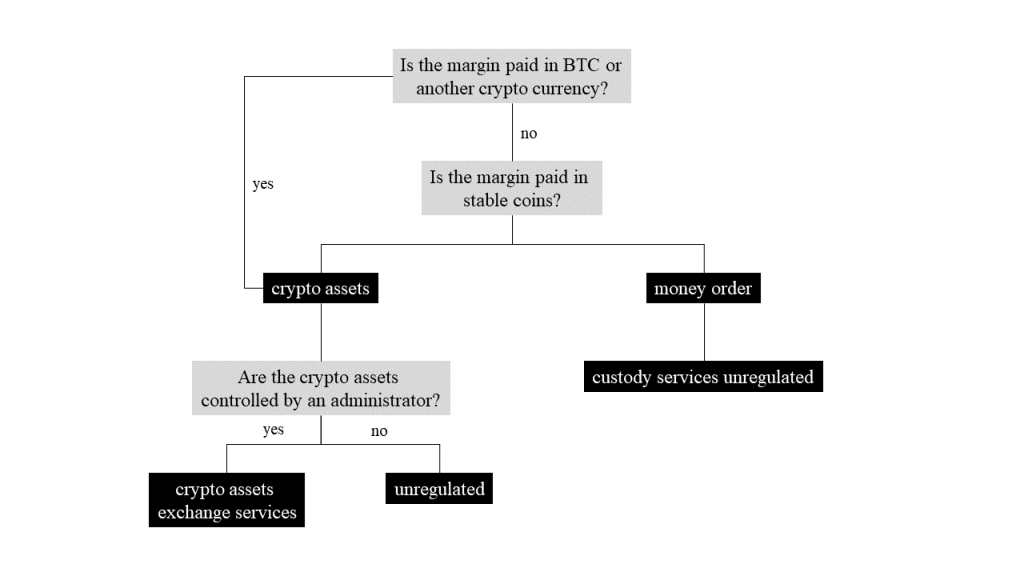

Typically, the margin is either paid in bitcoin or some other cryptocurrency or, as in the case of dydx, stable coins. While bitcoin and other crypto currencies constitute crypto assets under the Payment Services Act (PSA), stable coins must be analyzed more carefully. Depending on their design, stable coins may either be classified as crypto assets or money orders. The safekeeping of stable coins that are crypto assets is regulated as crypto asset exchange services as written below. Where stable coins constitute money orders, regulations do generally not apply to the safekeeping of stable coins in Japan.

The custody of crypto assets for others is generally considered a crypto asset exchange service under the PSA and must be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA). Since custody requires control over the crypto assets, services are not covered if a platform does not have ability to transfer a user’s funds. The fact that funds are locked into a smart contract does not automatically mean that the platform does not have control over the funds. In particular, where the platform is able to modify the smart contract in such a way that allows it to transfer the funds, the platform will still be deemed to have control. It is therefore necessary to analyze the administrator rights carefully, and where necessary to modify them to avoid registration.

Crypto derivatives constitute financial instruments within the meaning of the FIEA. This applies irrespective of whether they are settled in fiat or cryptocurrencies. Entities engaging in derivatives transactions must therefore generally register with the FSA as a FIBO. An exception may however be made for entities engaging in transactions with certain counter parties.

Since crypto derivatives platforms do not engage in transactions with their users but only provide the marketplace, they must generally not register as FIBO with regard to entering into transactions as such.

For users something different might apply since they can act both as makers, i.e. liquidity providers, or takers. A registration is only required however if the respective person engages in derivative transactions in the course of their business. In general, the activities on the exchanges are more akin to proprietary trading which is unregulated. This applies irrespective of whether the trader acts as a maker or taker.

It should be noted that the provision of a leverage exceeding 2x to retail investors is not allowed under Japanese laws.

The principle “same business same rules” also applies to derivatives. DeFi and offshore projects may therefore be required to register with the FSA if they want to offer their services to users in Japan. For fully decentralized projects without an operator something different may apply. The law, at least, is silent in this respect and leaves room for interpretation. DeFi projects that have transferred control over the protocol to their users, may therefore decide to enter the Japanese market without registration. For other projects smart technical solutions backed by legal arrangements may ease the regulatory burden and should be considered.

If you want to learn more, please feel free to contact us any time.

With 24 registered crypto asset exchanges, the Japanese market has become increasingly competitive over the last few years. Constrained by regulations, Japanese exchanges have further only been able to list a fraction of the tokens traded elsewhere. At the same time, new restrictions on margin trading and additional license requirements for crypto derivatives have made it increasingly difficult to compete internationally.

The latest market developments, namely the shift from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake consensus mechanisms and the increasing popularity of yield farming, provide an excellent opportunity to exchanges, however, to add further services and to exploit additional revenue streams.

In this article, we analyze the regulatory environment for exchanges that want to use their customers’ funds for staking and yield farming services, highlight potential pitfalls, and provide some legal considerations for implementing these services.

For more information on the regulatory environment for DeFi lending platforms, please visit our previous article.

| KEY FINDINGS Registered exchanges can generally provide staking and yield farming services in Japan if they (1) remain in control over the staked funds and (2) do not transfer the economic risk resulting from staking and yield farming to their users. |

Blockchains depend on some form of consensus mechanism. The mechanism ensures that all nodes in the network agree on a single state and that the transaction history becomes immutable. The proof-of-work (PoW) consensus mechanism was the first successfully deployed. Given its high energy consumption and low transaction throughput, new consensus mechanisms have evolved. The most prominent is the proof-of-stake (PoS) consensus mechanism.

PoS generally uses a pseudo-random selection process to select a node as a validator. Selection criteria vary from platform to platform and include, among others, a node’s wealth, staking age, or other factors.

The validator of a block generally receives a block reward together with transaction fees paid by the users of a network. According to stakingrewards.com, the staking rewards for the bigger platforms are typically between 3-9 percent of the staked amount.[1]

While the Ethereum community has discussed the transition from a PoW to a PoS consensus mechanism for some time, other platforms have pressed ahead. Current forms range from pure PoS to different types of delegated PoS (DPoS). For the latter, a user does not directly participate in the validation of transactions but delegates this activity to others, the delegates.

Table 1: Overview of different consensus mechanisms using some form of PoS

| consensus mechanism | funds controlled by user | direct distribution to user | penalties | |

Ethereum 2.0 |

PoS |

yes, but temporarily locked in a smart contract |

yes |

yes |

|

|

tezos |

liquid PoS |

baking (PoS) |

yes, but locked in a smart contract as a bond |

yes |

yes |

|

delegating (DPoS) |

yes, different keys for transactions and staking |

no |

no |

||

|

EOS |

DPoS |

yes, but temporarily locked in a smart contract |

not necessarily any distribution to delegators |

no |

|

|

Algorand |

pure PoS |

yes |

yes |

no |

|

|

LISK |

DPoS |

yes, but temporarily locked |

no |

only lock-up for an extended period |

|

Yield farming allows token holders to generate passive income from their crypto holdings as well. Instead of participating in staking, yield farming requires users to lock their funds into a lending protocol such as Compound or MakerDAO, which in turn allows others to borrow from the pooled funds at a certain interest rate.

Many of the lending protocols currently involve an additional type of token, which is used as an incentive for both lenders and borrowers. Together with these incentives, annual yields of up to 100 percent were possible until last month. More recently, the price of most governance tokens dropped, however, and brought the yield for lenders down to more realistic levels.

Currently, most DeFi lending activities focus on the Ethereum blockchain. Since Ethereum still uses the PoW, yield farming and staking do not compete directly. However, this will change with the roll-out of Ethereum 2.0 over the next five to ten years.

Registered exchanges in Japan can engage in the exchange of crypto assets and the management of their users’ funds – all, of course, within the boundaries set by the Payment Services Act (PSA) and subsidiary legislation.

The definition of crypto asset exchange services in the PSA does not only lay out the services subject to registration. It also determines the scope of regulated services a registered exchange may provide.

According to Section 2(5) PSA, the following services are considered crypto asset exchange services:

Since all exchanges in Japan are centralized exchanges, they provide exchange and custody services.[2] Accordingly, they must also follow the rules for crypto custodians when providing staking or yield farming services.

Under the new regulations, exchanges are generally required to hold 95 percent of their users’ funds in a cold wallet or secure them by means which provide a similar level of security. The remaining 5 percent can be stored in a hot wallet but must be fully backed by an exchange’s own funds.

It should be noted that in both cases, the exchange remains in full control over its users’ funds. A user is, therefore, generally able to withdraw his funds at any time. This even applies in cases similar to a bank run and must be borne in mind when preparing the terms and conditions for yield farming and staking services.

As shown above, PoS mechanisms come in different shapes and sizes. It is, therefore, necessary to analyze the design carefully when assessing the admissibility of staking services.

As much as the admissibility depends on the design of the respective consensus mechanism, it depends on the contractual arrangements in place. Both components and their interaction with each other must, therefore, be analyzed comprehensively. This applies in particular because the right contractual arrangements may neutralize some of the negative effects resulting from design choices.

The first thing to consider is who controls the staked funds. If it is the user, which is highly unlikely if not impossible in case of centralized exchanges, there are no concerns. The same is true if the funds are controlled and remain under the control of the exchange after being used for staking.

In most PoS models, a user must lock his tokens in a smart contract for staking. While the tokens are temporarily locked in the smart contract, i.e. the time they are used for staking and in some cases an additional period, they can generally be unlocked at any time.

The only one who can unlock the funds from the smart contract is the person controlling the private key corresponding to the address that was initially used to lock the funds in the smart contract. Except for slashing staked funds in case of misbehavior or excessive downtimes, the smart contract does not control the staked amount. In particular, it is not able to transfer the funds independently.

Since the funds remain under the control of an exchange, the situation is not different from any other situation where the funds are associated with an address controlled by an exchange.

In the case of DPoS, the situation is generally not different from the situation described above. An exchange using funds for delegation services does not lose control over the funds at any time. This applies even if the funds are locked in a smart contract for delegation.

In some cases, namely the liquid PoS by tezos, the exchange must not even send a users’ funds to a smart contract. Instead, there are two keys – one for controlling the funds and another one for delegation. Unlike in other PoS models, it is therefore not even necessary to send the funds to a smart contract and withdraw them when a user wants to withdraw his funds from the exchange.

Since the smart contracts used for staking do generally not control the locked funds, the situation is comparable to the situation where the funds are associated with an address controlled by the exchange. In both cases, the funds can only be transferred by the person controlling the private keys. If these keys are stored offline, the level of security is generally the same for funds locked in the smart contract and funds associated with an ordinary address. That being said, there is no reason to treat the two situations differently.

Most PoS consensus mechanisms require the user to lock funds into a smart contract. Even if the funds are unlocked, the holder of the private key may not receive the funds directly. An exchange staking its users’ funds may, therefore, not be able to respond to a withdrawal request immediately.

An exchange may either counter the delay by using its own funds or provide in its terms and conditions that there may be delays if a user also wants to use the exchange’s staking services. The terms may further lay out different periods for different protocols or simply use the longest period as a standard.

Some PoS consensus mechanisms provide for slashing in case of misbehavior, excessive downtimes, or other violations of the protocol’s rules. In other words, the person violating the rules loses a certain amount of staked funds.

Where the economic risks and benefits are borne by the user, staking is more akin to investments than to deposits. Investment activities are, however, regulated under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) and require a different license. A crypto asset exchange license is not sufficient.

Crypto asset exchanges that do not have the necessary licenses must, therefore, implement measures to prevent users from bearing the economic risk of staking. One way to do so is by reconciling losses with the exchange’s own funds.

The legal considerations are generally the same for PoS and yield farming. In short, an exchange may not carry out activities where the users run the risk of making a loss.

Compared to staking, there is one fundamental difference, however. An exchange will lose control over the lent amount. The control over the asset is transferred to the lending protocol, which in turn lends the funds to other users.

In exchange for supplying the funds to the protocol, an exchange does, however, receive another token which represents an increasing share in the protocol’s funds. By transferring these tokens to the protocol, an exchange can generally redeem the locked funds from a lending protocol at any time. This applies at least if there is sufficient liquidity. In the case of illiquidity, an exchange may have to wait for a certain amount of time until the redemption may be completed. An exchange may bridge this time either by using its own funds or putting a contract in place that allows it to wait with the refund until there is sufficient liquidity on the respective market.

The private keys controlling the tokens issued by the protocol can be stored in a cold or hot wallet like any other key in possession of the exchange. Insofar, nothing different applies.

The PSA does not generally prohibit yield farming or staking services. This applies at least if the economic risks of staking or yield farming are not transferred to the user. It is also necessary to take a closer look at the respective PoS mechanism and adjust, where appropriate, the contractual documentation.

With respect to yield farming, it should be noted that DeFi lending has been prone to exploits by flashloans. Exchanges that wish to enter the space are therefore well advised to analyze potential attack vectors carefully.

Given the current vulnerabilities of DeFi protocols, we expect that only staking services will get more traction in the near future. Yield farming will, however, follow in the mid- to long term. If you want to discuss the technical and legal implementation of PoS and staking services, please feel free to contact us at any time.

[1] Staking Rewards, Trusted Data. Stakeable Assets., retrieved from https://www.stakingrewards.com/proof-of-stake (accessed on 03/08/2020).

[2] Unlike decentralized exchanges, centralized exchanges require users to transfer their funds to an address controlled by the exchange. The user does not have any control over the funds until he instructs the exchange to transfer the funds to an address specified by him.

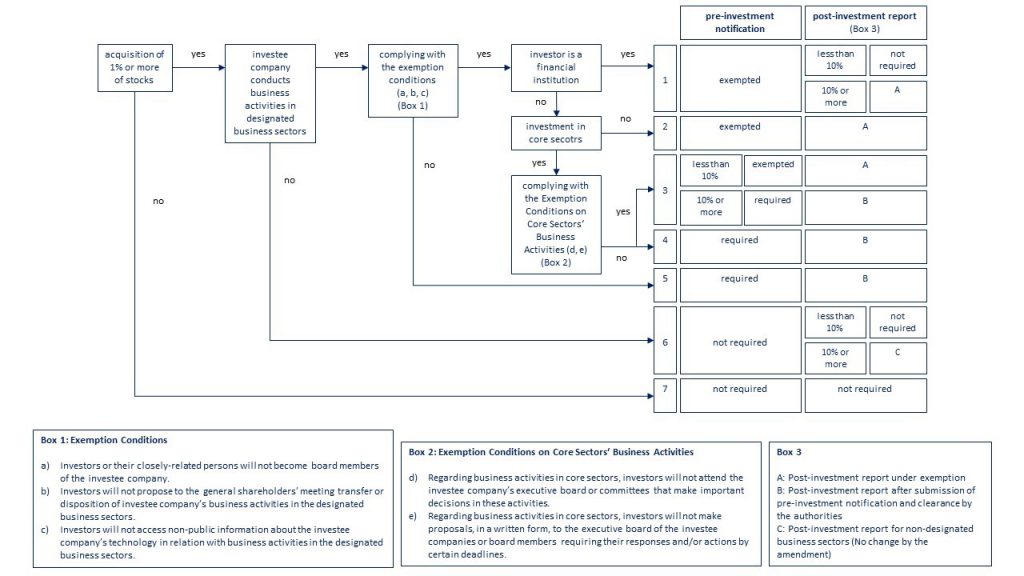

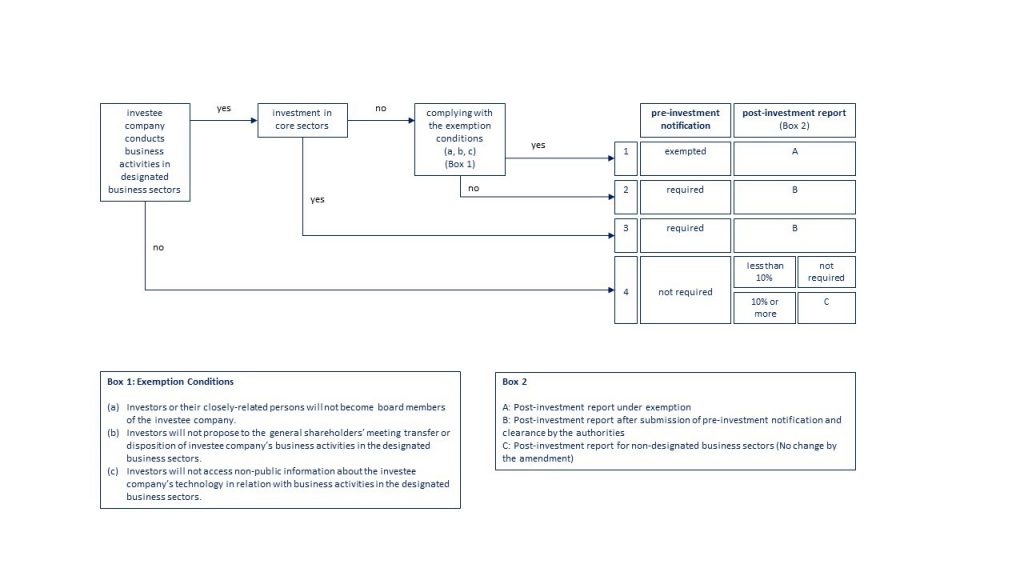

Earlier last year, the Japanese government started to tighten the rules on foreign direct investments (FDI) by adding, among others, certain sectors in the information and communication technology and software development to the list of restricted industries. Foreign investments in companies that operate in these sectors are generally subject to pre-transactional approval by the relevant authorities if they exceed certain thresholds. With the latest amendments, the legislator lowered the threshold for the acquisition of shares in listed companies from 10% to 1%. At the same time, exemptions were introduced allowing foreign investors under certain conditions to buy shares above these thresholds without obtaining prior approval.

The changes entered into force on May 8, 2020 and apply to all investments on or after June 7, 2020.

The Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (Act) aims “to enable the proper development for foreign transactions and the maintenance of peace and security in Japan”. To ensure that these goals are achieved, the Act limits among others foreign investments in sectors which are vital to national security (e.g. infrastructure, aviation, nuclear technology).

Only in 2019, the legislator added the ICT industry, etc. to the list of restricted sectors. The move reflected the increasing importance of those industries in a national security context and was largely in line with developments in other jurisdictions.

This time, the legislator extended the definition of foreign investors and lowered the threshold for investments in listed companies irrespective of their industry. At the same time, some exemptions to the pre-transactional approval requirement were introduced for certain types of investors.

The Act defines foreign investors as (i) individuals who are non-residents, (ii) entities established under foreign laws or having their principal office in a foreign state, (iii) Japanese entities which are directly/indirectly controlled by persons set forth in item (i) and (ii), and (iv) entities in which the majority of directors are persons set forth in item (i). A person is considered to control an entity within the meaning of item (iii) if it holds 50% or more of the voting rights in a company. Whether the voting rights are held directly or through other entities controlled by the respective person is irrelevant.

With the latest amendment (iv) partnership-type investment funds were added to the definition of foreign investors provided, however, 50% or more of the total capital of the fund was contributed by persons indicated under item (i) and (ii) above.

The term “inward direct investment or equivalent action” is defined broadly. It includes (i) the acquisition of shares (both on primary and secondary markets), (ii) consenting to certain substantial changes to a company’s scope of business after the acquisition of the shares, (iii) the establishment of a branch offices, (iv) the issuance of loans of at least JPY 100 million and a term of one or more years[1], and (v) the succession of business by means of business transfer, absorption type company split or merger.

The acquisition of shares in a listed company is only considered a direct investment under the Act if the investor holds at least 1% of the outstanding shares or voting rights following the transaction. Whether the investor holds the shares or voting rights directly or through closely related persons is irrelevant. The definition of closely related persons is rather complex. At its core, it includes affiliates and business partners of a foreign investor where the investor is a company, and relatives of the investor if the investor is a natural person.

Out of the 1465 sectors under the Japan Standard Industrial Classification 155 sectors – including pharmaceuticals and medical devices for the containment of infectious diseases such as COVID-19 as per recent amendment – are designated business sectors under the regulations. As discussed in more detail in section 5 below, foreign direct investments into designated business sectors may trigger pre-transactional approval requirements.

The regulations further distinguish between core-designated sectors and non-core sectors. While some industries belong exclusively to core or non-core designated sectors, others may be covered by both.

Listed Companies: The Ministry of Finance (MoF) published an exhaustive list indicating for all listed companies in Japan, whether their activities fall within non-designated sectors, designated sectors other than core sectors, or core sectors. The full list can be found on the website of the MoF.

Unlisted Companies: For unlisted and private companies, it is necessary to assess in each case whether the relevant business falls within the designated sectors – and if so under the non-core or core sector – as different notification requirements apply for exempted investors. The full list of designated sectors can be found on the website of the MoF as well (only Japanese).[2]

Foreign investments in companies operating in designated sectors are generally subject to pre-transactional approval by the relevant authorities via the Bank of Japan (BoJ). For listed companies, the approval requirement is triggered when an investor holds 1% of the outstanding shares or voting rights subsequent to the investment either on his own or together with closely related persons.

For unlisted companies there are no thresholds. Investments in companies operating in the designated sectors are therefore subject to BoJ approval irrespective of the amount invested and the shares or voting rights held following to the investment.

| threshold | |

| listed companies | 1% |

| non-listed companies | n/a |

Investors who fail to obtain pre-transactional approval by the BoJ may be ordered to dispose of all acquired shares.

The new regulations provide for exemptions from the pre-transactional approval requirement for certain types of investors but only if these investors meet additional criteria.

The blanket exemption is available to foreign financial institutions which are subject to Japanese regulations or equivalent foreign regulations. The definition includes, banks, securities firms, insurance companies, asset management companies, trust companies, registered investment companies, as well as high-frequency traders[3].

In order to qualify for the blanket exemption these entities or closely related persons must

| (a) | not become board members of the investee company |

| (b) | not propose at a general shareholders’ meeting the transfer or disposition of the investee company’s business in the designated sector(s) |

| (c) | not gain access to non-public information about the investee company’s technology concerning the designated sectors. |

Financial institutions complying with these requirements do not have to obtain pre-transactional approval via the BoJ. This applies irrespective of whether the investee company operates in core or non-core designated sectors and irrespective of the number of shares or voting rights held following the investment.

If an exempted investor holds 10% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment, it must however file a post-investment report with the BoJ.

Exemptions from the pre-transactional approval also apply to general investors (including sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds accredited by authorities). In contrast to the blanket exemption, it is necessary to distinguish between investments in companies operating in designated core sectors and companies operating in non-core sectors.

Non-core sectors: Investments in non-core sectors are exempted if the investor meets all the requirements under item (a) to (c) in section 6.1 above. It is however necessary to file a post-investment report, if the investor holds 1% of the shares or voting rights following the investment.

Core sectors: Investments in core sectors may only be exempted if the investor does not hold 10% or more of the shares or voting rights subsequent to the investment. In order to qualify for the exemption an investor must comply with the requirements under item (a) to (c) in section 6.1 above and must

| (d) | not attend the investee company’s executive board or committees that make important decisions on activities in the core sector |

| (e) | not make any proposals in writing to the executive board or board members requiring their responses and/or actions by certain deadlines. |

A post-investment report must also be filed in these cases provided the investor holds 1% or more of the shares[4] or voting rights following the investment.

Please note that a foreign investor is not required to obtain a pre-transactional approval if a company has only indicated restricted activities in its corporate documents (e.g. articles of incorporation, corporate registry) but has not operated in these sectors within 6 months prior to the investment. Even in this case, the foreign investor must however submit a post-investment report if he holds 10% or more of the voting rights of the investee company.

Investments that require pre-transactional approval must be notified to the BoJ before the investment is made. The notification must specify the purpose of the investment, the amount, the time and other information as specified by Cabinet Order. Once the notification is submitted, there is a 30-day waiting period during which the investment must not be executed. In practice the waiting period is generally shortened to 2 weeks. Under certain circumstances, the waiting period may, however, also be extended to a maximum of five months. To avoid unnecessary delays, foreign investors should engage in informal discussions with the relevant authorities prior to filing the notification.

Post-investment reports mainly serve statistical purposes and must be filed within 45 days after the respective investment is made.

Whether the latest amendments negatively affect the readiness of foreign investors to invest in Japanese companies remains to be seen. Given the newly implemented exemptions under the Act, it should however not hamper foreign investment unreasonably.

In any case, investors are well advised to check early whether their investments require pre-transaction approval by the BoJ and if so whether they are exempted. For listed companies this can be checked easily. For unlisted companies, it is necessary to assess in more detail whether the company falls under the designated sectors.

Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions in that regard and should you need our assistance.

[1] Loans issued by banks and other financial institutions in the course of trade are explicitly excluded from the definition.

[2] To see all items please visit https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-1.pdf, https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-2.pdf,https://www.mof.go.jp/

international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-3.pdf, https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_

kawase/fdi/index.htm#joubun (accessed 20/07/2020).

[3] High-frequency traders are only eligible for the blanket exemption if they are registered with the Financial Services Agency.

[4] Please note that the foreign investor will have to submit (i) a report after the investor holds 3% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment and (ii) a report for each acquisition after the investor holds 10% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment.

[5] MOF, Rules and Regulations of the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, p. 16 retrieved from https://www.mof.go.jp/english/international_policy/fdi/kanrenshiryou01_20200424.pdf (accessed 20/07/2020).

[6] Ibid, p. 17.

Mostly unrecognized by mainstream media, DeFi has gained increasing traction over the last few months. Large parts of its growth can be attributed to lending platforms such as Compound, Maker, and Aave, just to name a few. Broadly speaking, users of these platforms receive some form of interest in exchange for locking their assets into a smart contract, which in turn lends them to (other) users. Together with extrinsic rewards paid by these platforms, yields of up to 100 percent are currently possible. The process of optimizing yield through a combination of leverage and rewards is commonly referred to as yield farming and liquidity mining.

In this article, we will discuss the regulatory treatment of lending platforms under Japanese laws. Restrictions for users do not exist. In our next article, we will focus on the opportunities, Compound and other platforms provide to crypto asset exchanges in Japan, which currently face fierce competition and pressure under the new regulations.

The basic concept of yield farming and liquidity mining is to generate passive income from crypto assets. Yield farmers and liquidity miners generally try to put their assets to maximum use by utilizing a combination of lending and borrowing techniques on one or more lending platforms. Apps such as Instadapp help users to bridge different protocols and to leverage the full potential of DeFi by automating large parts of the lending and borrowing activities.

To explain how yield farming and liquidity mining work, we will use Compound, one of the biggest and currently most used platforms, as an example.[1]

In order to earn a yield on Compound, users must lock their assets in a smart contract. In turn, the smart contract issues new tokens (cTokens) at a predefined exchange rate. These tokens allow the user to earn a yield over time and to use them as collateral when borrowing funds via the platform.

cTokens do not provide recurring revenue to their holders. Instead, they represent a share in a pool of assets that constantly grows due to borrowers’ interest payments. With the price of cTokens increasing relative to the locked assets, cTokens generate a yield when used to withdraw the locked assets. The actual amount depends on the compound interests calculated by the protocol based on market dynamics, namely supply and demand.

In addition to the compound yield, lenders currently receive COMP tokens. These tokens allow their holders to propose and vote on changes to the protocol and are actively traded on exchanges. Only with COMP tokens, the current yields are possible at all.

When borrowing funds via Compound, a user must deposit cTokens as collateral. The maximum amount a user can borrow depends on the collateral factor of the deposited asset. This factor is set by COMP token holders. The collateral factor is generally higher for liquid, high-cap assets and lower for illiquid, small-cap assets. The collateral factor of ETH, for example, is currently set at 0.7. A user supplying ETH 100 to the protocol, would therefore be able to borrow up ETH 70 worth of assets via Compound.[3]

Where a user’s borrowing balance exceeds his borrowing capacity due to outstanding interests, the value of collateral falling or the borrowed assets increasing in price, the collateral will be liquidated automatically at a discount to the current market price.

Like lenders, borrowers currently receive an external reward in the form of COMP tokens for using the Compound platform. Every day, approximately 2,880 COMP are distributed – 50 percent to lenders and 50 percent to borrowers.

When analyzing the legal and regulatory environment for DeFi lending activities, it is necessary to break down the lending model into different components. First, it is necessary to analyze the tokens required for the protocol to work. In a second step, the activities involving each of the tokens must be analyzed in more detail. It should be noted, however, that it is not possible to view tokens and activities as separate components, but that it is necessary to consider the interaction between both for the analysis.

Compound and other lending platforms involve a number of different tokens. In the case of Compound, these tokens are (i) ETH and ERC-20 tokens supplied to the protocol, (ii) cTokens which are issued in exchange for the tokens supplied, and (iii) COMP which is issued as a reward and which constitutes the protocol’s governance token.

Under Japanese laws, tokens may either constitute crypto assets under the Payment Services Act (PSA) or electronically recorded transfer rights under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). Tokens neither covered by the definition of crypto assets nor electronically recorded transfer rights may not be regulated at all.

The PSA distinguishes between type I crypto assets and type II crypto assets. Type I crypto assets are proprietary values that can (i) be used for purchasing goods and services from unspecified persons, (ii) purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparties, (iii) and transferred electronically.

Type II crypto assets are property values that can (i) be mutually exchanged with unspecified persons for type I crypto assets and (ii) transferred electronically. Currency denominated assets such as fiat currencies and electronically recorded transfer rights are explicitly excluded from the definition of both type I and type II crypto assets.

The definition of electronically recorded transfer rights was added to the FIEA with the latest amendment. It covers electronically recorded values that represent type II securities which can be transferred electronically, and which do not have liquidity constraints.

Currently, most platforms, including Compound, allow users to deposit ETH, certain ERC-20 utility tokens[4], and different kinds of stable coins.

ETH is a typical type I crypto asset. ERC-20 utility tokens generally constitute type II crypto assets as they can easily be exchanged with type I crypto assets. The same most likely applies to wrapped bitcoin as they are currently not used for payment and can only be exchanged with type I crypto assets.

For stable coins, the legal classification depends on their exact features and underlying model. The most prominent stable coins, such as USDT and USDC, are based on an IOU model. Each token is backed by one USD.[5] As a result, they are likely to fall under the definition of currency denominated assets and are thus excluded from the definition of crypto assets under the PSA. For more information on the classification of different stable coins, click here.

cTokens represent a user’s balance in the Compound protocol. As the market earns interest, the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying assets. This raises questions as to whether cTokens represent beneficiary certificates in a money market fund (MMF) or interests in a collective investment scheme and therefore constitute electronically recorded transfer rights.

Beneficiary Certificates in an MMF

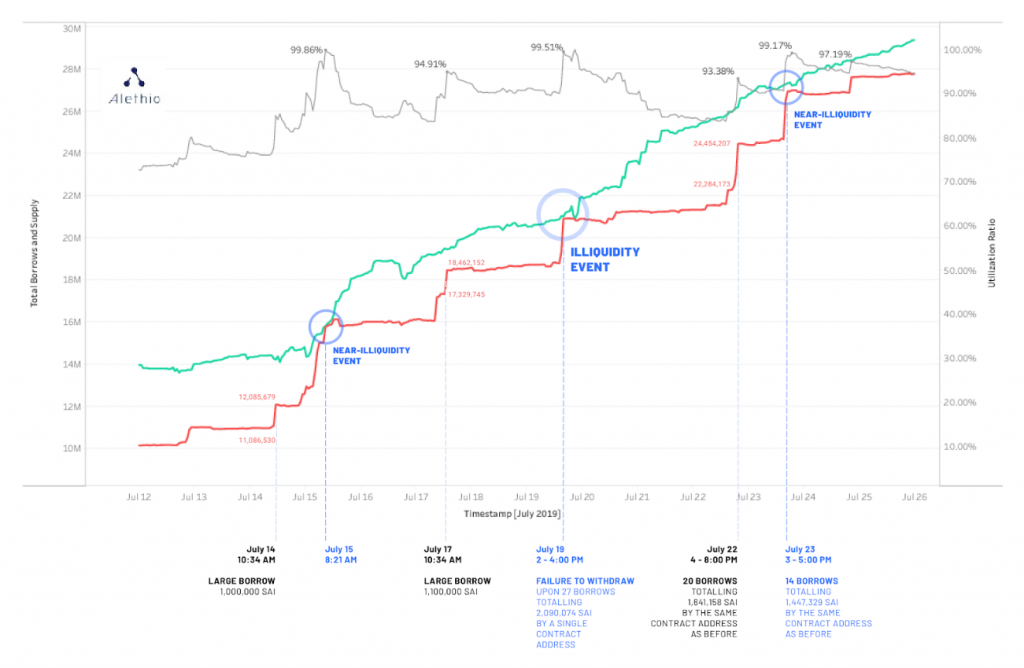

Traditionally MMFs are used as cash management vehicles for retail and institutional investors. Defining features are the payment of dividends, the fact that investors can redeem their certificates at any time, and the fact that MMFs seek to maintain a stable net asset value. The redemption of a substantial amount of beneficiary certificates may, however, result in a loss of liquidity and negatively affect the remaining certificates’ price.

The risk of illiquidity also exists in the case of Compound and other DeFi protocols. As the following graphic shows, it may be even more pronounced than for traditional MMFs.

The difference between Compound and traditional MMFs is that a user’s yield is independent of profits generated by the protocol. Rather than calculating the yield after repayment of the borrowed loans, the protocol uses the prevailing interest rate for each interval when calculating the compound interest rate. Whether a loan is fully paid back at any point in time or not, is irrelevant

It is further worth noting that the Compound protocol does not constitute a legal entity that could act as a trust. The protocol is also not controlled by a legal entity that may otherwise be seen as a principal.

Interests in a Collective Investment Scheme

The definition of collective investment schemes in the FIEA[7] is intentionally broad and covers various arrangements that are used to pool money for investment purposes. Investors in a collective investment scheme are entitled to participate in the earnings a scheme generates but bear a business risk at the same time. If the scheme suffers a loss, investors in the scheme suffer a loss as well.

The argument that Compound and other DeFi platforms do not pay dividends can also be used with regard to collective investment schemes. Unlike investors in a collective investment scheme, holders of cTokens earn a yield irrespective of profits generated by the platform. The yield solely depends on the accrued interests over time and is calculated by using the interest rate on the respective markets for each block.

While there is an illiquidity risk, lenders should generally not make a loss when using Compound. This is due to the over-collateralization and auto-liquidation of loans where the balance of the collateral is insufficient to support the loan. If this promise holds true, the situation is fundamentally different from collective investment schemes where investors may actually suffer a loss.

It may further be argued that cTokens do not fall under the definition of interests in a collective investment scheme as they do not represent rights. Rights, by definition, require a counterparty. In the case of DeFi, a counterparty does not exist. Instead, assets are collected and distributed via smart contracts according to predefined rules on a factual basis. Whether the regulator will follow this argument remains to be seen. Yet, we believe that there is plenty of room to argue that cTokens and similar arrangements do not fall under the definition of collective investment schemes and do, therefore, not constitute electronically recorded transfer rights under the FIEA.

Type II Crypto Assets

Since cTokens can be transferred electronically and exchanged with other tokens, they represent type II crypto assets under the PSA. The fact that the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying asset does not lead to different results. This is because their value is only driven by market forces, namely supply and demand. The protocol merely ensures that the value of cTokens does not decrease relative to the underlying asset over time.

Governance tokens issued by the Compound protocol constitute type II crypto assets. They can be exchanged with other crypto assets but are not used for payment. The fact that governance tokens provide the user with voting rights is irrelevant for the legal classification in the absence of other features.

The lending and borrowing of crypto assets are not regulated under Japanese laws. A banking license or money lending license is therefore not required.

The exchange of crypto assets is generally considered a crypto asset exchange business in Japan. This applies irrespective of whether the exchange is facilitated by a centralized exchange, a decentralized exchange (DEX),or another smart contract if there is a controller.

Whether the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA is not clear. Neither the PSA nor any subsidiary legislation contains a definition of exchange. Yet, there are good reasons to doubt that the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA and must, therefore, be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA).

cTokens are issued when a user supplies other tokens to the protocol. While this might look typical exchange of crypto assets, there is a fundamental difference. The user does not lose control over the initial amount deposited. cTokens more or less serve as a key to unlock the initial amount deposit and can be used at any time to do so – provided of course, there is sufficient liquidity. For typical exchanges, this possibility does not exist. The same applies to the exchange of cTokens for other crypto assets.

The issuance of governance tokens is not an exchange business as well. While the issuance of tokens in exchange for liquidity, is sometimes compared with ICOs the key difference is that there is no payment of consideration for receiving the tokens. Instead, the tokens are issued as a subsidy by the platform without additional consideration. It is therefore more akin to an airdrop where an issuer aims to promote his platform. Also, in these cases, it is not necessary to register as a crypto asset exchange.

The definition of crypto asset exchange services also includes custody business. When tokens are locked into a smart contract, this may generally be considered custody under the PSA. It may however be argued that this does not apply where the smart contract creator does not have control over the contract. In these cases, only the user is able to unlock the supplied amount by transferring cTokens to the smart contract and to release the funds. The automatic liquidation function does not change this result as the protocol creator does not have control over the funds at any point of time.

While DeFi has become increasingly popular over the last few months, it has not been on the radar of Japanese regulators so far. The good news is that certain protocols and tokens will most likely not fall under the FIEA. This will hopefully allow DeFi to get some more traction on the Japanese market and allow exchanges to add DeFi to their services.

As so often, the devil is in the detail. Much depends on the structure of the overall arrangement and the token design. Existing projects that intend to enter the Japanese market are therefore well advised to analyze their protocol and token design carefully.[8] The same applies to crypto asset exchanges that intend to add further services in the future to become more attractive in an increasingly competitive market.

We will analyze the possibilities resulting from DeFi and PoS for exchanges in our next article. Stay with us.

DISCLAIMER

The DeFi protocols mentioned in this article, in particular Compound, are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the article, not all details of the protocol and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project. By no means, the explanations should be understood as a legal opinion regarding DeFi protocols mentioned in this article.

[1] According to DeFi Pulse, 28.03 percent of the USD 2.51 billion total value locked in DeFI is currently locked in Compound, DeFi Pulse, retrieved from https://defipulse.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[2] Compound, retrieved from https://compound.finance/ctokens (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[3] It is worth noting that a user’s collateral would immediately be liquidated to a certain extent with the first interest payment becoming due.

[4] For this paper, utility tokens are understood as tokens that give token holders access to an application or a service and which serve as a platform-internal currency.

[5] For USDT, the accounts have not been properly audited so far.

[6] Alethic, Illiquidity and Bank Run Risk in DeFi, retrieved from https://medium.com/alethio/overlooked-risk-illiquidity-and-bank-runs-on-compound-finance-5d6fc3922d0d (accessed 10 July 2020).

[7] Article 2(2)(v) FIEA.

[8] DeFi, by definition, does not necessarily involve a central entity controlling the project. It may, therefore, be difficult for the regulator to get hold of the persons behind the project. If a project aims to get more traction in the regulated space, there is however no way to cut some corners or to circumvent regulation altogether.

| fund type | examples | type of securities under the FIEA | securities registration requirements for public offerings | disclosure requirements | |

| self-offering | third-party offering | ||||

| corporation | investment corporations (domestic) | type I | not possible | type I FIBO | yes, for funds investing >50 percent in securities (exemptions in case of private placements) |

| investment corporations (foreign) | type I | not possible | type I FIBO | ||

| KK | type I | no registration | type I FIBO | ||

| GK | type II | no registration | type II FIBO | ||

| trust | unit trusts (domestic) | type I | type II FIBO | type I FIBO | |

| unit trusts (foreign) | type I | type II FIBO | type I FIBO | ||

| partnership | partnerships under the Civil Code | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | |

| silent partnerships under the Commercial Code | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

| limited partnerships for investment under the Limited Partnership Act for Investment | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

| limited liability partnership under the Limited Liability Partnership | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

Where interests in a fund are offered by the fund itself to Qualified Institutional Investors (QII) only, the fund does not have to register as a Financial Instruments Business Operator (FIBO) and may instead submit a comparably simply notification to the Financial Services Agency (FSA) – so-called Article 63 exemption. This exemption applies only in case of self-offerings. Thirds parties distributing units or interests in a fund are not covered by the exemption and must register as a FIBO.

You will find more information on the regulatory environment for partnership-type funds and the Article 63 exemption in our article on funds regulations in Japan.

A fund is an investment vehicle that (i) collects money (or other assets) from investors, (ii) invests the pooled money into securities, real estate, crypto, and other assets and (iii) distributes profits arising out of the investments to the investors. In Japan, there are three legal forms to set up a fund: (i) trusts, (ii) corporations, and (iii) partnerships. Mutual funds are structured as unit trusts under the Investment Trust and Investment Corporation Act (Law No. 198 of 1951, as amended), while J-REITs are corporations established under the same act. Funds structured as partnerships typically target a smaller number of investors and are generally more flexible in terms of investment, target investors, and timing of entry and exit than the other types.

In this article, we first outline the legal and regulatory environment for funds that invest primarily in securities and which are structured as partnerships. In the second part, we then take a closer look at crypto funds. Funds investing in real estate and commodities must comply with different laws and will be covered in a separate article.

Partnership-type funds under Japanese laws may be set up as (i) partnerships under the Civil Code (Law No. 89 of 1896, as amended), (ii) silent partnerships under the Commercial Code (Law No. 48 of 1899, as amended), (iii) limited partnerships for investment under the Limited Partnership Act for Investment (Law No. 90 of 1998, as amended), and (iv) limited liability partnerships under the Limited Liability Partnership Act (Law No. 40 of 2005, as amended).

Depending on the percentage of foreign investors[1] and the percentage of investments in foreign assets[2], foreign partnership-type funds such as limited partnerships in the Cayman Islands may be more suitable. This topic will, however, be covered in a separate article.

The characteristic features of each legal form will be outlined in the following.

According to Article 667(1) of the Civil Code, a partnership is established when each of the parties promises to make a contribution and to engage in a joint undertaking. When using a partnership under the Civil Code as a fund, the partners are jointly responsible for the day-to-day operations of the fund by the act, though the partners typically delegate the management of the fund to one or more partners.

For funds set up as partnerships under the Civil Code, there are no investment restrictions. All partners assume unlimited liability, and in general, all profits and losses are distributed to the partners depending on their overall contributions.

A silent partnership is a contract between a business operator and an investor according to Article 535 of the Commercial Code.

The operator of a silent partnership carries out the business under his/her own name and on his/her own account. The silent partner does not play an active role and is only obliged to make contributions. In turn, he/she is entitled to participate in the profits generated by the business of the operator. The liability of a silent partner is stipulated in a silent partnership agreement and is usually limited to the amount of his/her contribution.

Under the applicable laws, there are no investment restrictions for silent partnerships.

Since a silent partnership agreement is a two-party agreement, an operator concludes individual contracts with each investor.

A limited partnership for investment is a partnership under the Limited Partnership Act for Investment[3] and consists of partners with a limited liability, limited partners (LP), and at least one general partner (GP) with an unlimited liability. For funds structured as a LPS, a GP is responsible for operating the fund’s business, while LPs are not involved in the day-to-day operations of the fund. A LP’s liability is limited to the amount of his/her contribution.[4]

LPS are subject to investment restrictions.[5] A LPS must, for example, not invest more than 50 percent of its total funds in foreign securities.[6]

A limited liability partnership is a partnership under the Limited Liability Partnership Act (LLP Act)[7]. The personal liability of all partners is limited to the amount of their contributions.[8] A LLP is generally managed jointly by all partners. While it is possible to delegate day-to-day operations to a single partner, important decisions must be made jointly by all partners of the LLP. Entering into an agreement concerning the disposition or acquisition of material assets or borrowing of large amounts of money are matters requiring the consent of all partners.[9]

Though there are no investment restrictions for LLPs, LLPs are not used as investment vehicles very often. One of the main use cases for LLPs as investment funds is the establishment of a movie production committee.

TABLE 1: SUMMARY OF PARTNERSHIP-TYPE FUNDS IN JAPAN

| Partnerships under the Civil Code | Silent Partnerships | Investment LPS | LLP | |

| Partners | general partners | an operator and a silent partner | general partner(s) and limited partners | limited partners |

| Agreement | agreement between all partners | one-to-one agreement between operator and silent partner | agreement between all partners | agreement between all partners |

| Registration | n/a | n/a | necessary | necessary |

| Ownership of Assets | partnership | operator | Investment LPS | LLP |

| Day-to-day operation of the fund | jointly by all partners (delegation to single partners or third parties possible) | operator | general partner | jointly by all partners (delegation to single partners or third parties possible to a certain degree) |

| Investment restrictions | n/a | n/a | investments limited to those assets listed in Article 3(1) of the LPS Act for Investment (e.g. shares, certain types of bonds, and investments in silent partnerships) restrictions ≤ 50 percent of total funds in foreign securities, and no investment in crypto assets | no investment restrictions |

The Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) treats certain partnership interests, namely interests in so-called “collective investment schemes”, as securities. The definition of collective investment schemes under the FIEA is as follows:

Activities involving collective investment schemes are subject to disclosure and registration requirements as well as conduct controls. The solicitation of interests in a collective investment scheme to investors is considered a solicitation of securities. The management of a fund’s assets is an investment management business under the FIEA. Both must be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA)[10].

The public offering or secondary distribution of highly liquid securities such as shares, or bonds (type I securities) is generally subject to disclosure requirements and must be registered with the FSA.[11]

The disclosure requirements for the offering or distribution of less liquid securities such as interests in a partnership type fund (type II securities) are less strict under the FIEA.[12]

The public offering or private placement of interests in a collective investment scheme[13] may only be carried out by registered Type II Financial Instrument Business Operators (Type II FIBO).[14]

This also applies to the self-offering of partnership interests to Japanese investors by a GP or a partner with similar authorities if the fund is a collective investment scheme as explained above.

To get registered as a Type II FIBO a person must fulfill certain criteria. This includes among others meeting minimum capital requirements and hiring fit and proper personnel (e.g. a compliance officer with eligible knowledge and experience) for operating the business. Only where an applicant meets all requirements stipulated in the FIEA and subsidiary legislation the FSA must approve an application for registration.

With respect to funds the term investment management business is understood as the management of money or other property invested by a person connected with investments primarily in securities or derivatives which are based on investment decisions requiring the valuation and analysis of such instruments.[15] In this context, “primarily” means that generally more than 50% of the assets under management are invested in securities or derivatives. To conduct an investment management business a company must register as an Investment Management Business Operator.[16] Similar to Type II FIBO persons engaging in the investment management business must meet certain criteria, including minimum capital requirements and hire fit and proper personnel. Only where an applicant meets all requirements, the FSA must register an applicant as Investment Management Business Operator.[17]

The registration requirements in Section 3.2 and 3.3 above do not apply to the fund if the fund entrusts all sales and investment management activities to another party which is registered as a Type II FIBO and/or Investment Management Business Operator with the FSA.

When a partnership-type fund entrusts all “external” activities concerning its public offering or private placement to a registered Type II FIBO, the GP of the fund does not have to register as a Type II FIBO.[18]

When a partnership-type fund delegates certain activities completely to a registered Investment Management Business Operator, the GP of the fund does not have to register as an Investment Management Business Operator. In order for the exemption to apply, the fund must comply with the requirements set out in Article 1-8-6(1)(iv) of the FIEA Enforcement Order and Article 16(1)(x) of the Cabinet Office Order on Definitions under Article 2 of the FIEA.

The main requirements are as follows:

Exemptions to the registration requirements outlined in Section 3.2 and 3.3 above may apply, under the exemption as a Specially Permitted Business for Qualified Institutional Investors (QII), etc. (QII Exemption also known as Article 63 exemption). Many funds that target QIIs and other sophisticated investors make use of this exemption.

To fall under the QII exemption a fund must solicit (i) one or more QII, and (ii) less than 49 qualified investors other than QII. None of the investors must fall under the category of non-qualified institutional investors.[19][20]

Persons who conduct business under the QII Exemption are not obliged to register as Type II FIBO or Investment Management Business Operator but have to submit a comparably simple notification to the FSA. The notification must include certain information about the fund (type of the fund), the GP (or a partner with an equivalent authority) and the investing QII(s). Foreign GPs must appoint Japanese representatives for the notification. Persons filing the notification are subject to additional requirements, including conduct controls almost equivalent to registered Type II FIBO or Investment Management Business Operators. Furthermore, a fund making use of such notification is subject to ongoing disclosure requirements for each fiscal year.

For your information, the QII Exemption requirements were tightened in 2015, mainly due to an increase of losses caused by malicious actors. Before the 2015 amendments, a fund was able to solicit retail investors. Now, the scope is limited to qualified investors. Qualified investors are investors who have a certain level of knowledge and experience in investments and include listed companies, corporations with capital of JPY 50 million or more, and individuals having more than JPY 100 million investment-type financial products as assets and more than one year investment experience.

The definition of qualified investors was however considered to be too narrow for investments in venture funds[21]. For venture funds the definition of qualified investors was therefore broadened and additionally includes (former) officers of listed companies as well as specialists (e.g. certified public accountants, lawyers).[22]

TABLE 2: INVESTORS OTHER THAN QII UNDER THE QII EXEMPTION

| Prior to the 2015 revision | Since the 2015 revision | ||

| All partnership-type funds | Anyone | Ordinary partnership-type funds | Listed companies, corporations with capital of 50 million yen or more, individuals having more than JPY 100 million assets and more than 1 year investing experience after opening their securities accounts. |

| Venture funds | In addition to the above, officers of listed companies, persons who have been officers of listed companies within the past five years, and specialists. | ||

TABLE 3: BUSINESS REGISTRATION AND NOTIFICATION REQUIEMENTS UNDER THE FIEA FOR THE SALES AND MANAGEMENT OF FUNDS

| General registration requirements | Registration requirements in case of complete entrustment to a registered third party | Availability of the QII exemption | |

| SALES | |||

| Sales by issuer itself | Type II FIBO registration | n/a (for the third party, Type II FIBO registration) | yes, but Article 63 FIEA notification |

| Sales by third party (on behalf of the issuers) | Type II FIBO registration | n/a if sales activities are sub-delegated to a registered third party (rarely the case) | Type II FIBO registration (QII exemption does not apply) |

| INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT | |||

| Management of funds that invest +50% in securities by GP | registration of GP as Investment Management Business Operator | n/a (for the third party, Investment Management Business operator registration | yes, but Article 63 FIEA notification |

| Management of funds that invest +50% in securities by third party | third party must register as Investment Management Business Operator | n/a if management activities are sub-delegated to a registered third party (rarely the case) | third party must register as Investment Management Business Operator Registration (QII exemption does not apply) |

| Management of other funds (incl. crypto funds) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

A crypto fund can be understood as (i) a fund that primarily invests in crypto assets, (ii) a fund that collects crypto assets from its investors, or (iii) a fund that is tokenized. In the following, we will outline the applicable regulations in more detail and discuss the impact of the latest revision of the FIEA on tokenized investment funds.

Funds investing in crypto assets are subject to the same rules and regulations as other partnership-type investment funds. In case of self-solicitation, operators of the fund must therefore generally register as Type II FIBO.[23] Exemptions from the registration requirement apply for the solicitation of QII, etc.[24] Also, if a fund delegates its sales activities to a registered Type II FIBO, the fund operator must not register as a FIBO itself.

The operator of an investment fund that mainly invests in securities and derivatives must generally register as Investment Management Business Operator. Since crypto assets are neither considered securities nor derivatives under the FIEA this does not apply for funds operators that mainly invest in crypto assets. Please note, however, that security tokens constitute securities under the FIEA. Investing in security tokens may therefore trigger registration requirements provided that certain thresholds are passed (≥ 50 percent of the total investments into security tokens).

It is sometimes argued that a fund investing into crypto must register as a crypto asset exchange service provider under the Payment Services Act (PSA). However, it is unlikely that registration is necessary considering the fact that a registration is only required if the trading is carried out as a “business”. Where the trading is carried for investment purposes, the requirements stipulated by the FSA for a “business” are not met.

The definition of funds requires among others the collection of money. Before the 2020 revision of the FIEA, crypto assets were not considered money within the meaning of the FIEA. This has changed with the new laws entering into force on May 1, 2020. Under the new laws crypto assets are deemed money within certain provisions of the FIEA[25], including the provisions on collective investment schemes. The raising of crypto assets is therefore covered by the FIEA.

With the 2020 revision of the FIEA the concept of electronically recorded transfer rights (ERTR) were introduced. Article 2(3) of the FIEA defines ERTR as follows:

| “Electronic Recorded Transfer Right” are rights that fulfill all requirements from (1) to (3) and do not fall under (4): Rights listed in Article 2(2) of the FIEA (funds, beneficial interest in a trust, membership rights of general partnership company, etc.)which are recorded electronically, andmay be transferred by using an electronic data processing system. Cases specified by Cabinet Office Ordinance taking into account the liquidity constraints and other circumstances. |

Interests in a fund which are tokenized are generally considered ERTR. Given their (potentially) increased liquidity they are subject to the same regulations as more liquid type I securities. Third parties engaging in the sale of tokenized interests must therefore register as Type I FIBO.[26] The self-solicitation of tokenized interests by a fund is subject to the same registration requirements as the self-solicitation of funds in general. A fund must therefore register as a Type II FIBO and, if ≥50% of the money is invested in securities or derivatives, as an Investment Management Business Operator, unless an exemption applies. The QII exemption and the exemption in case of entrustment of all sales and investment activities to third parties also apply to tokenized funds.[27]

Since ERTR are generally subject to the same regulations as type I securities disclosure requirements apply. An issuer of ERTR is therefore obliged to prepare a prospectus[28] and to register the offering with the FSA[29]. In addition to the initial disclosure, ongoing disclosure requirements apply.[30] Something different only applies in the case of private placements. These are placements with QII, professional investors or a small number of investors (≤ 50 investors) only.

For more detailed information on security token offerings (STOs), please click here.

TABLE 4: BUSINESS REGISTRATION AND NOTIFICATION REQUIREMENTS UNDER THE FIEA FOR THE SALE AND MANAGEMENT OF TOKENIZED FUNDS

| General registration requirements | Registration requirements in case of complete entrustment to a registered third party | Availability of the QII exemption | |

| SALES | |||

| Sales by issuer itself | Type II FIBO registration | n/a (for the third party, Type II FIBO registration) | yes, but Article 63 FIEA notification |

| Sales by third party (on behalf of the issuers) | Type I FIBO registration * | n/a if sales activities are sub-delegated to a registered third party (rarely the case) | no, Type I FIBO registration necessary * |

| INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT | |||

| Management of funds investing primarily in crypto assets by GP or third party | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Management of funds that invest +50% in security tokens by GP | registration of GP as Investment Management Business Operator | n/a (for the third party, Investment Management Business Operator registration | yes, but Article 63 FIEA notification |

| Management of funds that invest +50% in security tokens by third party | third party must register as Investment Management Business Operator (**) | n/a if management activities are sub-delegated to a registered third party (rarely the case) | no, registration as Investment Management Business Operator necessary |

* These are differences from table 3 for non-tokenized funds. In case of non-tokenized funds, a type II FIBO registration is required.

TABLE 5: DISCLOSURE REGULATION

| Type of solicitation | Investors | Obligation to disclose | |

| Private placement | Private placement with QII only* | QII only | generally not applicable |

| Private placement to a small number of investors* | ≤49 investors | ||

| Private placement to specified investors* | specified investors only | ||

| Public offerings | unlimited number of investors | securities registration statement ** (continuing disclosure of semi-annual reports, extraordinary reports, etc.) | |

* Technical measures must have been taken to restrict resale.

** When the total issue price is less than JPY 100 million the obligation to file a securities registration statement does not apply (Article 4(1)(v) of the FIEA).

[1] This may affect the application of pass-through taxation.

[2] There are restrictions on investments in foreign securities for Limited Partnerships for Investments as discussed in more detail below.

[3] Article 2(2) of the Limited Partnership Act for Investment.

[4] Article 7(1), 9(1) and (2) of the Limited Partnership Act for Investment.

[5] Article 3(1) of the Limited Partnership Act for Investment.

[6] Article 9 of the Enforcement Order of the Limited Partnership Act for Investment.

[7] Article 2 of the LLP Act.

[8] Article 15 of the LLP Act.

[9] Article 12 of the LLP Act.

[10] Even if all of the requirements from (1) to (3) are fulfilled, there are certain cases where the interests are not considered securities. These are cases (i) where all of the fund’s business is carried out with the consent of all investors, and where (ii-a) all of the investors regularly engage in the invested business, or where (ii-b) the investors participate in the invested business using their specialized skills which are indispensable for the continuation of the business (Article 2(2)(v)(i) of the FIEA, Article 1-3-2 of the FIEA Enforcement Order).

[11] Article 4(1) of the FIEA.

[12] If a fund’s interests fall under the definition of “securities investment business rights” or “electronic record transfer rights”, they are subject to disclosure regulations (Article 3(iii)(i)-(ha) of the FIEA). The term “securities investment business rights” generally covers cases where more than 50% of a fund’s contributions are invested in securities. In that case, the full disclosure requirements apply if the number of persons acquiring fund interests exceeds 500 (Article 2(3)(iii) of the FIEA, Article 1-7-2 of the FIEA Enforcement Order). For further details on electronic record transfer rights (i.e. tokenized interests in a fund), see Section 4.3 below.

[13] As discussed in Section 2 above, interests in a collective investment scheme are deemed securities according to Article 2(2)(v) or (vi) of the FIEA.

[14] Article 28(2)(i) and Article 2(8)(vii) of the FIEA.

[15] Article 2(8)(xv)(ha) and Article 28(4) of the FIEA.

[16] Article 29 of the FIEA.

[17] FSA’s Public comment Response No. 190, etc. (2007.7.31).

[18] FSA’s Public Comment Response No. 103, etc. (2007.7.31).

[19] Article 63(1) of the FIEA, Article 235 of the Cabinet Office Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[20] Persons listed under Article 17-12(1) of the FIEA Enforcement Order and Article 233-2 of the Cabinet Office Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[21] A venture fund means a fund which invests more than 80% of its assets in shares of non-listed companies and satisfies the other requirements in Article 17-12(2) of the FIEA Enforcement Order, Article 233-4 and 239-2(1) of the Cabinet Office Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[22] Article 17-12(2) of the FIEA Enforcement Order, Article 233-3 of the Cabinet Office Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[23] Article 28(2)(i) and Article 2(8)(vii) of the FIEA.

[24] Article 63 of the FIEA.

[25] Article 2-2 of the FIEA and Article 1-23 of the FIEA Enforcement Order.

[26] Article 28(1), Article 2(8) and Article 2(9) of the FIEA.

[27] In order to use the QII exemption for the self-offering of ERTR, ERTR must satisfy the following requirements in addition to the requirements which apply to non-tokenized fund, Article 63(1)(i) of the FIEA and Article 234-2(1)(iii) of the Cabinet Office Order on Financial Instruments Business. For ERTR which are sold to QII: Technical measures have been taken to prevent the transfer of the ERTR to persons other than QII. For ERTR which are sold to specified investors other than QII: Technical measures have been taken to prevent the transfer of ERTR to QII or specified investors other than QII and such transfer shall be made in bulks.

[28] Article 13(1) and Article 15(1) of the FIEA.

[29] Article 4(1) of the FIEA.

[30] Article 24 of the FIEA.

An overview of the latest amendment to the Japanese crypto regulations. The changes entered into force on May 1, 2020 and affect cryptocurrency exchanges, custodians, crypto derivatives, and security token offerings (STOs).

The following presentation provides a high level overview.

Crypto_Law_Amendment(JP)_200427

Crypto_Law_Amendment(EN)_200424

For a more detailed explanation please visit our article on digital assets.

Cryptocurrency regulation in Japan is closely linked to the hack of the Japanese cryptocurrency exchange Mt. Gox in 2014 and Coincheck in 2018. As such, it is no surprise that the latest revision of the Payment Services Act (PSA) introduces detailed regulations on the safekeeping of crypto assets stored in hot wallets.