Category Archives: digital assets

Axie Infinity, the blockchain game by Sky Mavis, made major headlines recently. With more than 350,000 daily active players, the game is one of the most successful blockchain games so far. According to data from token terminal_, the game generated USD 581.7 million in revenue over the past 90 days. To put this into perspective, this is more than Ethereum over the same period of time.

So, what is behind the success of Axie Infinity?

Part of it can be attributed to the active Axie community and the cute pets – called Axies – that are used for battles. The other part is the new ‘Play-to-Earn’ gaming model. This model allows players to earn ‘real’ money by playing the game. Depending on the token price, the rewards are said to be somewhere between USD 300-500 per month. With the latest increase of AXS, they might be even higher.

The Play-To-Earn Model

To understand how the ‘Play-to-Earn’ model works, it is necessary to take a closer look at the game and the tokens involved.

There are basically three types of tokens in the game.

- Axie Infinity Shards (AXS)

- Smooth Love Potion (SLP)

- Axies, items, lands (NFTs)

To play the game players need at least three Axies. The Axies can be bought on the marketplace and currently cost around USD 200 or more.

To breed new Axies, players need 4 AXS and a certain number of SLP. To control the Axie population, it becomes increasingly expensive to breed Axies with same parents. After being used for breeding 7 times, Axies become sterile and cannot be used for further breeding.

| breed count | breed number | SLP cost |

| (0/7) | 1 | 150 |

| (1/7) | 2 | 300 |

| (2/7) | 3 | 450 |

| (3/7) | 4 | 750 |

| (4/7) | 5 | 1200 |

| (5/7) | 6 | 1950 |

| (6/7) | 7 | 3150 |

As all assets in the game are represented by NFTs and all rewards are paid in AXS or SLP, there are different ways for players to earn income:

» farming SLP and AXS by playing quests or battling other players

» participating in tournaments

» breeding new Axies and selling them on the marketplace

» speculating on rare Axies

In the future, it will also be possible to use AXS for staking. Staked AXS will allow token holders to earn additional AXS from the staking and treasury pool.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

Now that we know the basic gaming mechanics and the functions of each token, it is time to get a better understanding of the legal and regulatory environment in Japan. As the results of the analysis vary considerably, it is necessary to assess each activity and token individually.

Farming of AXS/SLP: The farming of SLP and AXS by playing quests or battling other players is generally subject to the limitations under the Improper Premiums and Misleading Representations Act (IPMR). The IPMR provides limits for items and other assets that can be given away for ‘free’. In the case of play-to-earn models where players must make an initial investment to play the game, the amount that can be given away for free is limited to JPY 100,000 or 2 percent of the initial sales, whichever is higher, or – for initial investments below JPY 5,000 up to 20 times the price of the initial investment.

Gambling laws do generally not apply as users are not required to pay any fees to qualify for the rewards. The fact that users must purchase three Axies to play the game is irrelevant as the purchase is neither directly nor indirectly linked to the rewards earned by playing quests or battling other players.

As users are not required to pay any fees or other consideration – time and effort spent for playing the game are not considered – there is no purchase or exchange of crypto assets. Crypto asset regulations do therefore not apply to the issuance of AXS and SLP.

Tournaments: Where players are required to pay a fee to participate in a tournament and win rewards, there is a high chance that both the organization of the tournament and the participation in the tournament is considered illegal gambling. Something different only applies where the fees are only used to cover the expenses of the organizer. The expenses may include prizes for the winning players or teams.

Breeding of Axies: Since a user must pay a certain amount of SLP to breed new randomly generated Axies, there is a possibility that the breeding of new Axies is considered illegal gambling.

Selling Axies: When selling items combined with the promise of future returns, companies must comply with the Specified Commercial Transaction Act. Under the act, companies must not engage in certain advertising efforts and must disclose specific information, including the company’s name, to prospects. Given the ambiguous wording of the act, it is uncertain whether it applies to the sale of Axies by Sky Mavis. For sales by users, the act is irrelevant.

Selling AXS, SLP, NFTs by Users: The sale of AXS, SLP, and NFTs by the user is not regulated under Japanese laws.

Marketplace for AXS, SLP, NFTs: AXS and SLP are considered crypto assets under Japanese laws. Anyone who offers a marketplace for the exchange of AXS and SLP would therefore generally have to register as a crypto asset exchange. The same would apply to custodial wallets that manage the private keys controlling the users’ AXS and SLP.

NFT marketplaces for Axies, items, and lands are not regulated in Japan.

DISCLAIMER

The play-to-earn mechanism of Axie Infinity is only used for illustrative purposes. Given the format of the article, not all details of the game mechanics and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator, or a legal opinion prepared by us or another law firm. By no means, should the explanations be understood as a legal opinion.

Decentralized finance – more commonly known as DeFi – has gained increasing traction over the last few months. With new services and platforms being launched every week, the environment has become increasingly complex despite its short history.

This article provides an overview of the key building blocks of DeFi and the regulatory implications under Japanese laws.

KEY BUILDING BLOCKS OF DEFI

1. decentralized exchanges

2. automated market makers

3. lending platforms

4. aggregators

5. vaults

6. derivatives

DEX

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) provide users with a marketplace where they can buy and sell crypto assets. The basic concept of DEXes is similar to that of centralized exchanges. Stated differently, DEXes typically maintain order books and matching engines.

In some cases, both the order book and matching engine are on-chain, in other cases they are off-chain and only the settlement occurs on-chain.

Examples

From a regulatory perspective it is necessary to distinguish between the order book/order matching and the settlement.

Depending on the degree of decentralization, i.e. the degree a creator of a DEX can access the funds or control the smart contract via admin rights, activities may either be regulated or unregulated.

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- order book/order matching >> crypto asset exchange service +/-

- safekeeping of deposited crypto assets in smart contract for settlement >> crypto asset exchange service in form of custody service +/-

|

|

custodial |

non-custodial |

regulated |

|

off-chain order book |

+ |

yes |

|

|

+ |

yes |

||

|

on-chain order book controlled |

+ |

yes |

|

|

+ |

yes |

||

|

on-chain order book not controlled |

+ |

no |

|

|

+ |

yes |

AMM

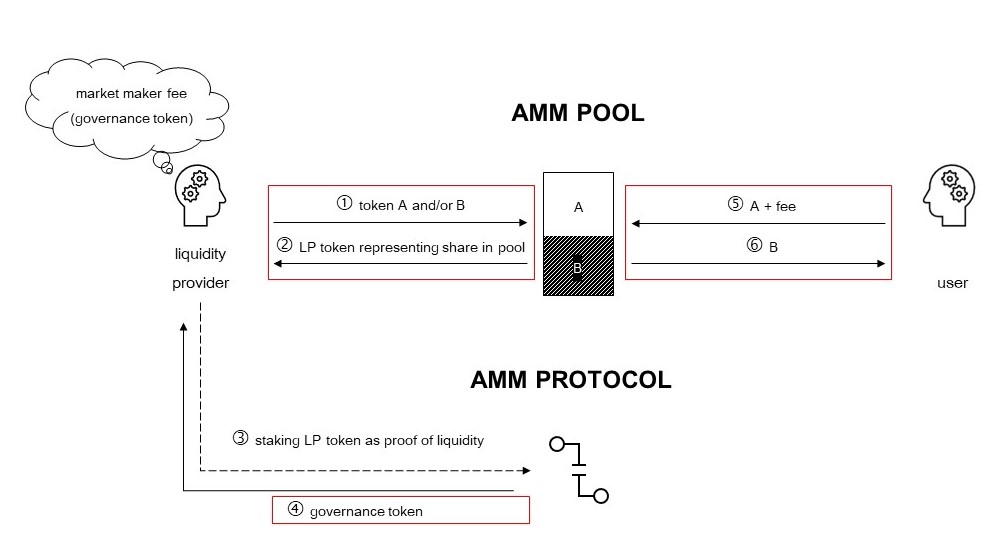

Automated Market Makers (AMMs) do not have order books. Instead they use liquidity pools that consist of at least one pair of crypto assets. The price of each crypto asset is measured against the other asset in the pool.

Uniswap for example uses the following formula to determine the price of each crypto asset in the pool:

x * y = k

In this equation, x and y represent the number of each token in the pool. While x and y vary over time, k remains constant and allows the AMM to determine the price of each asset at any point of time.

If a user exchanges ETH for DAI in an ETH/DAI pool, for example, the price of DAI becomes more expensive relative to ETH. This opens arbitrage opportunities if the ETH price in the pool deviates from the actual market price. To make use of the arbitrage opportunity a trader must only supply DAI to the pool and withdraw ETH. As a result, the price of ETH will be rebalanced and aligned with the overall market price.

The liquidity in the pools is provided by liquidity providers (LP). In exchange for providing liquidity LPs participate in the fees charged for interacting with the pool and in some cases receive a governance token as additional incentive.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- exchange of crypto asset with LP token (1)(2) >> crypto asset exchange service -/

- exchange of crypto assets (5)(6) >> crypto asset exchange service -/

- safekeeping of deposited crypto assets in smart contract controlling the AMM pool >> crypto asset exchange service in form of custody service +/-

- issuance of LP token (2) >> issuance of security +/-

- issuance of incentives (4) >> crypto asset exchange service similar to ICO -/

LENDING

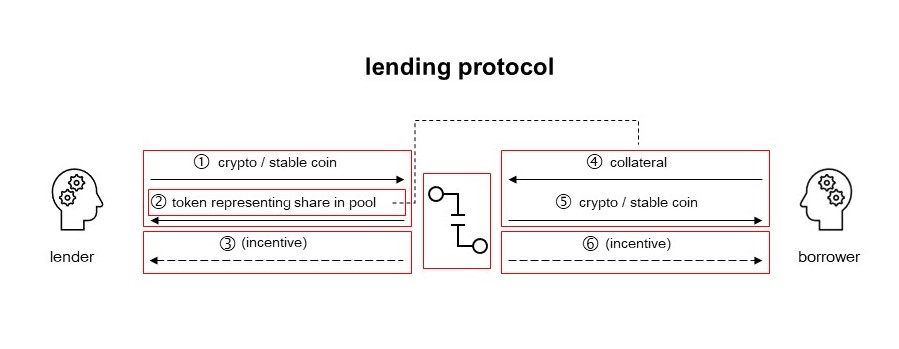

To borrow funds via one of the existing lending platforms, users must deposit crypto assets to the protocol. When supplying funds to the lending protocol, lenders receive a token representing their share in the lending pool. This token may be used as collateral when borrowing funds from the protocol.

Depending on the protocol, an additional token, typically in form of a governance token, may be issued to both the lender and borrower as an incentive to use the platform.

Borrowers pay interests to the protocol which either forwards them directly to the lender or releases them once the lender decides to unlock his funds from the protocol.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- exchange of crypto asset with token representing share in pool (1)(2) >> crypto asset exchange service +/-

- exchange of token representing share in pool with crypto asset (4)(5) >> crypto asset exchange service +/-

- safekeeping of deposited crypto assets in smart contract controlling the lending pool >> crypto asset exchange service in form of custody service +/-

- issuance of token representing share in pool (2) >> issuance of security /-

- issuance of governance tokens as incentive (3)(6) >> crypto asset exchange service /-

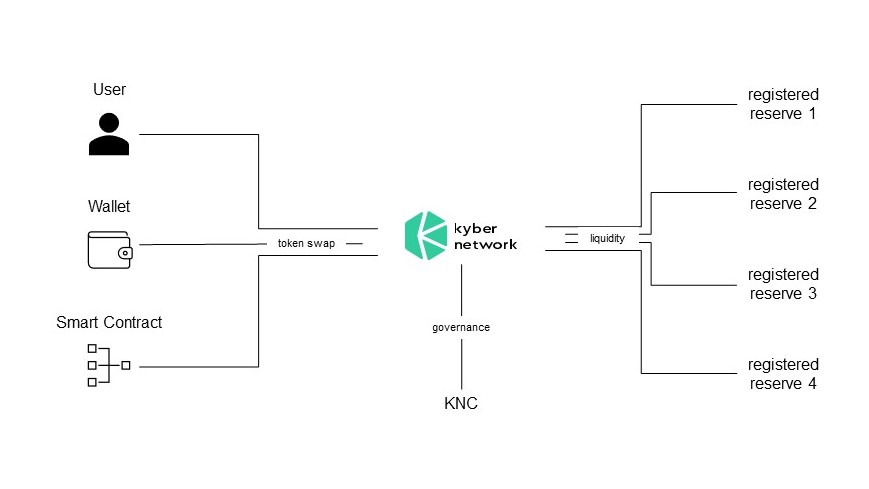

AGGREGATORS

Aggregators connect users, wallets, and smart contracts with liquidity. By doing so, they allow them to swap tokens for the best price available across multiple platforms.

Other aggregators constantly look for the best yield and distribute the supplied funds accordingly.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- intermediary services for the exchange of crypto assets >> crypto asset exchange service +/-

- search of and execution at best price >> investment advice -/

VAULTS

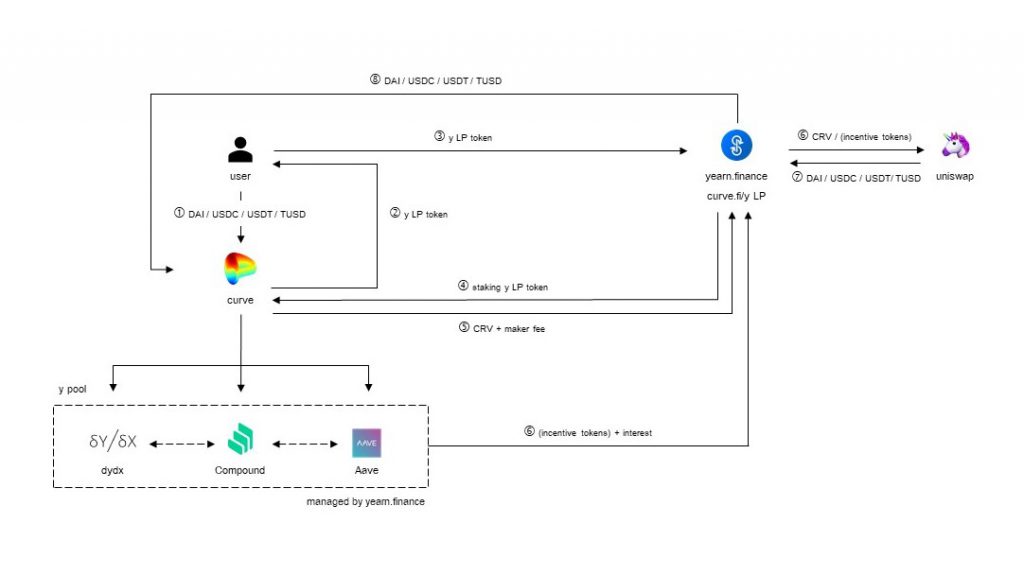

Vaults automatically optimize the returns on the funds supplied to them. To do so, they plug into multiple AMMs and lending protocols and move the funds wherever they generate the highest returns.

Where AMMs and lending protocols issue tokens as incentive, vaults automatically sell and reinvest them into the vault. One of the most prominent examples is yearn.finance.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- deposit of y LP token to vault (3) >> crypto asset exchange service in form of custody service /-

- allocation of crypto assets to pools with highest yield >> investment advice /-

DERIVATIVES

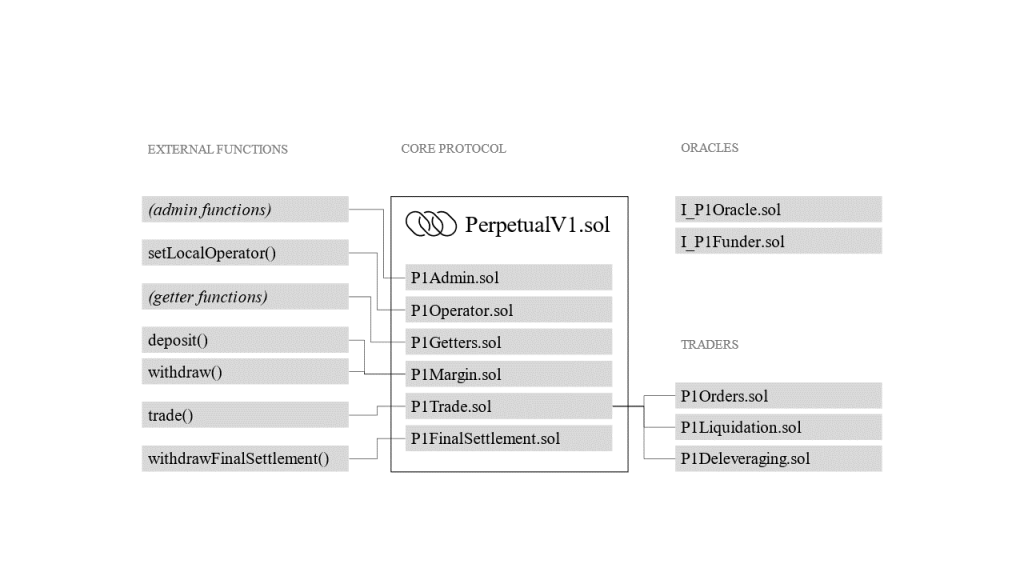

Derivatives platforms allow users to speculate and hedge their positions. For efficiency and cost reasons exchanges such as dydx use a hybrid off-chain/on-chain solution. The order book and order matching is performed off-chain while the margins paid by users of the platform are maintained by the protocol on-chain.

The infrastructure most derivatives exchanges operate on is similar to that of DEXes.

Examples

(Potentially) Regulated Activities

- order book/order matching >> financial instrument business operator license +/-

- deposit of margin to smart contract managing deposited funds >> crypto asset exchange service +/-

DISCLAIMER

THIS DOCUMENT IS FOR GENERAL INFORMATION purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice; thus, it may not be relied upon regarding a specific legal issue or problem. The projects mentioned in this document are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the document not all details of the token design and underlying business model have been considered, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project.

Crypto derivatives have become increasingly popular and account for over 90 percent of the total trading volume in Japan. Internationally, crypto derivatives have gained increasing traction as well. Only in June, Deribit reported that BTC options on the exchange have reached a new all-time high with a total of USD 1.4 billion open interest. Almost at the same time, the daily exchange volume of CME bitcoin futures reached USD 1.3 billion.

The success of crypto derivatives has also caught much attention in the DeFi space. Projects such as dydx try to replicate the success of their peers while giving users more control over their funds.

Before diving into derivatives on dydx, namely perpetual futures, we will first explain how perpetuals work. In the second part, we will then analyze each step from the deposit of margins to the trading of derivatives in more detail.

Key Findings

| Derivatives exchange services | Crypto derivatives are financial instruments. A platform providing exchange services must therefore generally register as a type I financial instruments business operator. This may not apply for completely decentralized platforms without an operator. |

| Deposit of margin | Deposit-taking activities may be considered a crypto asset exchange service that must be registered with the FSA. This applies to both centralized and – depending on the functionality of the smart contract and admin rights – decentralized projects. |

| Derivatives transactions | Platforms themselves do generally not engage in crypto derivatives transactions directly. They do therefore not have to register as a financial instruments business operator with the FSA in respect to the trading activities. Despite providing liquidity on exchanges, users do generally not have to register with the FSA. In most cases, their activities are likely considered proprietary trading which is unregulated. |

From forward contracts to futures to perpetuals

One of the best ways to understand perpetuals is to look at forward contracts and standard futures first.

Forward contracts: Forward contracts are bilateral agreements according to which the parties trade a specified quantity of a particular good at a certain price at a predefined date in the future. The contract is typically negotiated between the parties and tailored to their needs. A unilateral transfer of rights and obligations is generally not possible.

Futures: Futures are similar to forward contracts in that they also concern the trade of a specified quantity of a particular good at a certain price at a predefined date in the future. Unlike forward contracts, futures are however highly standardized and traded on exchanges. For trades on the exchange, the exchange becomes the buyer to each seller and the seller to each buyer. The users of the exchange therefore only bear the counterparty risk of the exchange but not the default risk of the other party.

Perpetual contracts: Perpetual contracts – for the large part – are perpetual futures, i.e. futures without a maturity date. Often provided via offshore jurisdictions, they allow traders to get leveraged exposure to bitcoin or other crypto assets. Typically, the margin requirements are 1 percent of the contract value for the initial margin and 0.75 percent for the maintenance margin. Where the margin falls below the prescribed thresholds, the position is automatically liquidated by the exchange. In some cases, the position is completely liquidated at once. In other cases, the liquidation occurs incrementally.

To ensure that the price of perpetuals does not deviate too much from the index price of the underlying asset, perpetual contracts use a certain funding mechanism. Where the perpetual contract is traded above the index price of the underlying asset, the trader holding the long position must pay the difference to the trader holding the short position and vice versa. Funding payments are calculated in regular intervals. In some cases, these intervals only account for milliseconds.

Most exchanges maintain an insurance fund to cover losses from bankrupt traders. Only if the insurance fund is depleted, losses from bankrupt traders are socialized.

| Criterion | Collateral | Futures | Perpetuals |

| Buyer-seller interaction | Direct | Via exchange | Via exchange |

| Contract terms | Can be tailored | Standardized | Standardized |

| Unilateral reversal | Not possible | Possible | Possible |

| Default-risk borne by | Individual parties | Exchange | Individual parties |

| Default controlled by | Collateral | Margin accounts | Margin accounts and insurance fund |

Perpetuals on dydx

Perpetuals traded on dydx are not different from perpetuals traded elsewhere. Unlike other platforms dydx uses a different approach for the trading and settlement, however, by utilizing a hybrid on-chain/off-chain approach.

While the order book and the order matching is off-chain, all other actions are performed by smart contracts on-chain. These smart contracts are either developed by dydx or third parties (e.g. MakerDAO BTC-USD Oracle). Some of them have backdoors for administrators.

According to dydx, the hybrid solution is meant to combine the best of both worlds, i.e. off-chain speed and efficiency, and on-chain security.

In order to trade on dydx users have to pay a margin to dydx’s protocol. If the margin falls below the maintenance margin, an account may be liquidated. In the liquidation process anyone may assume the margin and position balances of the liquidated account, provided of course, he has sufficient margin on his own.

Where an account falls short and has a negative net value the admin of the perpetual smart contract or a third party can call an offsetting account to take over the balance. This account is typically the insurance fund maintained by dydx. If the insurance fund is depleted, the admin may determine another account with a high amount of profit and margin to take over the balance.

Regulations in Japan

From a regulatory point of view, there are three different activities that must be assessed independently: (i) exchange services for derivatives, (ii) safekeeping of the margin, and (iii) engaging in derivatives transactions.

Trading Platform

Crypto derivatives platforms are generally not considered financial instruments markets under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). Yet, it is still necessary to register as a type I financial instruments business operator (FIBO) when operating a platform. This also applies to entities that use hybrid solutions, i.e. an off-chain order book and matching engine combined with on-chain settlement. The hybrid solution of dydx, for example, would be subject to registration requirements.

Something different may apply where the order book and matching engine are on-chain and where there is no operator. The smart contracts should further not be controlled by the project’s developers. Projects that have originally controlled the entity but subsequently transferred control to the community may not be covered by the registration requirement anymore. Where the project team remains the majority owner of the governance tokens, it may still be seen as the operator of the platform. A careful analysis is therefore necessary.

Deposit of Margin

Users who wish to trade perpetuals must generally deposit a margin. This applies to both centralized and decentralized platforms, whereas for the latter, the amount is not paid to the platform, but a smart contract deployed by the platform.

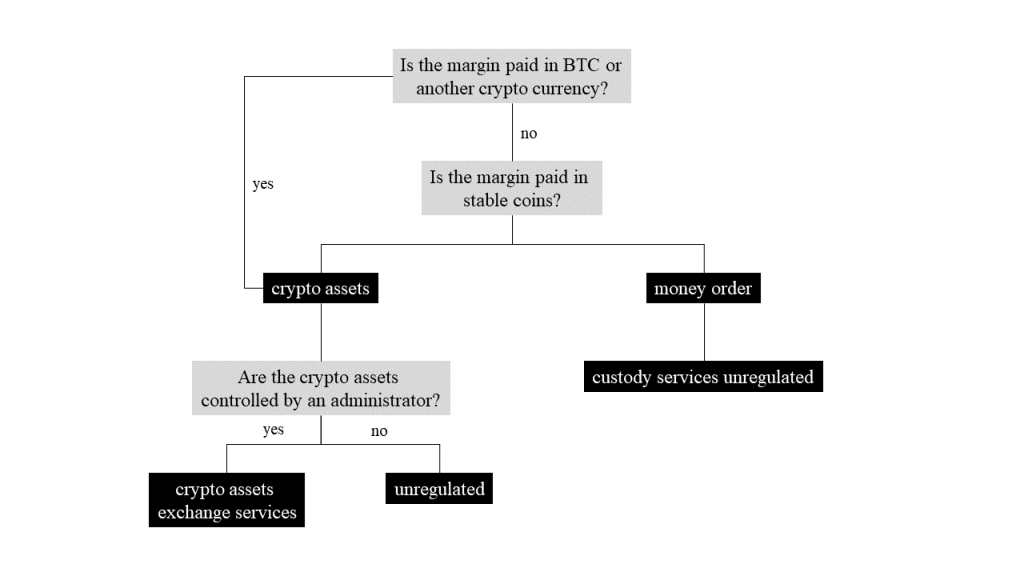

Typically, the margin is either paid in bitcoin or some other cryptocurrency or, as in the case of dydx, stable coins. While bitcoin and other crypto currencies constitute crypto assets under the Payment Services Act (PSA), stable coins must be analyzed more carefully. Depending on their design, stable coins may either be classified as crypto assets or money orders. The safekeeping of stable coins that are crypto assets is regulated as crypto asset exchange services as written below. Where stable coins constitute money orders, regulations do generally not apply to the safekeeping of stable coins in Japan.

The custody of crypto assets for others is generally considered a crypto asset exchange service under the PSA and must be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA). Since custody requires control over the crypto assets, services are not covered if a platform does not have ability to transfer a user’s funds. The fact that funds are locked into a smart contract does not automatically mean that the platform does not have control over the funds. In particular, where the platform is able to modify the smart contract in such a way that allows it to transfer the funds, the platform will still be deemed to have control. It is therefore necessary to analyze the administrator rights carefully, and where necessary to modify them to avoid registration.

Derivatives Transactions

Crypto derivatives constitute financial instruments within the meaning of the FIEA. This applies irrespective of whether they are settled in fiat or cryptocurrencies. Entities engaging in derivatives transactions must therefore generally register with the FSA as a FIBO. An exception may however be made for entities engaging in transactions with certain counter parties.

Since crypto derivatives platforms do not engage in transactions with their users but only provide the marketplace, they must generally not register as FIBO with regard to entering into transactions as such.

For users something different might apply since they can act both as makers, i.e. liquidity providers, or takers. A registration is only required however if the respective person engages in derivative transactions in the course of their business. In general, the activities on the exchanges are more akin to proprietary trading which is unregulated. This applies irrespective of whether the trader acts as a maker or taker.

It should be noted that the provision of a leverage exceeding 2x to retail investors is not allowed under Japanese laws.

Conclusion

The principle “same business same rules” also applies to derivatives. DeFi and offshore projects may therefore be required to register with the FSA if they want to offer their services to users in Japan. For fully decentralized projects without an operator something different may apply. The law, at least, is silent in this respect and leaves room for interpretation. DeFi projects that have transferred control over the protocol to their users, may therefore decide to enter the Japanese market without registration. For other projects smart technical solutions backed by legal arrangements may ease the regulatory burden and should be considered.

If you want to learn more, please feel free to contact us any time.

With 24 registered crypto asset exchanges, the Japanese market has become increasingly competitive over the last few years. Constrained by regulations, Japanese exchanges have further only been able to list a fraction of the tokens traded elsewhere. At the same time, new restrictions on margin trading and additional license requirements for crypto derivatives have made it increasingly difficult to compete internationally.

The latest market developments, namely the shift from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake consensus mechanisms and the increasing popularity of yield farming, provide an excellent opportunity to exchanges, however, to add further services and to exploit additional revenue streams.

In this article, we analyze the regulatory environment for exchanges that want to use their customers’ funds for staking and yield farming services, highlight potential pitfalls, and provide some legal considerations for implementing these services.

For more information on the regulatory environment for DeFi lending platforms, please visit our previous article.

| KEY FINDINGS Registered exchanges can generally provide staking and yield farming services in Japan if they (1) remain in control over the staked funds and (2) do not transfer the economic risk resulting from staking and yield farming to their users. |

DEFINITIONS

Proof-of-Stake (PoS)

Blockchains depend on some form of consensus mechanism. The mechanism ensures that all nodes in the network agree on a single state and that the transaction history becomes immutable. The proof-of-work (PoW) consensus mechanism was the first successfully deployed. Given its high energy consumption and low transaction throughput, new consensus mechanisms have evolved. The most prominent is the proof-of-stake (PoS) consensus mechanism.

PoS generally uses a pseudo-random selection process to select a node as a validator. Selection criteria vary from platform to platform and include, among others, a node’s wealth, staking age, or other factors.

The validator of a block generally receives a block reward together with transaction fees paid by the users of a network. According to stakingrewards.com, the staking rewards for the bigger platforms are typically between 3-9 percent of the staked amount.[1]

While the Ethereum community has discussed the transition from a PoW to a PoS consensus mechanism for some time, other platforms have pressed ahead. Current forms range from pure PoS to different types of delegated PoS (DPoS). For the latter, a user does not directly participate in the validation of transactions but delegates this activity to others, the delegates.

Table 1: Overview of different consensus mechanisms using some form of PoS

| consensus mechanism | funds controlled by user | direct distribution to user | penalties | |

Ethereum 2.0 |

PoS |

yes, but temporarily locked in a smart contract |

yes |

yes |

|

|

tezos |

liquid PoS |

baking (PoS) |

yes, but locked in a smart contract as a bond |

yes |

yes |

|

delegating (DPoS) |

yes, different keys for transactions and staking |

no |

no |

||

|

EOS |

DPoS |

yes, but temporarily locked in a smart contract |

not necessarily any distribution to delegators |

no |

|

|

Algorand |

pure PoS |

yes |

yes |

no |

|

|

LISK |

DPoS |

yes, but temporarily locked |

no |

only lock-up for an extended period |

|

Yield Farming

Yield farming allows token holders to generate passive income from their crypto holdings as well. Instead of participating in staking, yield farming requires users to lock their funds into a lending protocol such as Compound or MakerDAO, which in turn allows others to borrow from the pooled funds at a certain interest rate.

Many of the lending protocols currently involve an additional type of token, which is used as an incentive for both lenders and borrowers. Together with these incentives, annual yields of up to 100 percent were possible until last month. More recently, the price of most governance tokens dropped, however, and brought the yield for lenders down to more realistic levels.

Currently, most DeFi lending activities focus on the Ethereum blockchain. Since Ethereum still uses the PoW, yield farming and staking do not compete directly. However, this will change with the roll-out of Ethereum 2.0 over the next five to ten years.

LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

Registered exchanges in Japan can engage in the exchange of crypto assets and the management of their users’ funds – all, of course, within the boundaries set by the Payment Services Act (PSA) and subsidiary legislation.

Crypto Asset Exchange Services

The definition of crypto asset exchange services in the PSA does not only lay out the services subject to registration. It also determines the scope of regulated services a registered exchange may provide.

According to Section 2(5) PSA, the following services are considered crypto asset exchange services:

- the purchase and sale of crypto assets or exchange of crypto assets

- intermediary, brokerage, or agency services for the purchase, sale, and exchange of crypto assets

- the management of a user’s funds in relation to the purchase, sale, and exchange of crypto assets

- the management of crypto assets on behalf of another person

Since all exchanges in Japan are centralized exchanges, they provide exchange and custody services.[2] Accordingly, they must also follow the rules for crypto custodians when providing staking or yield farming services.

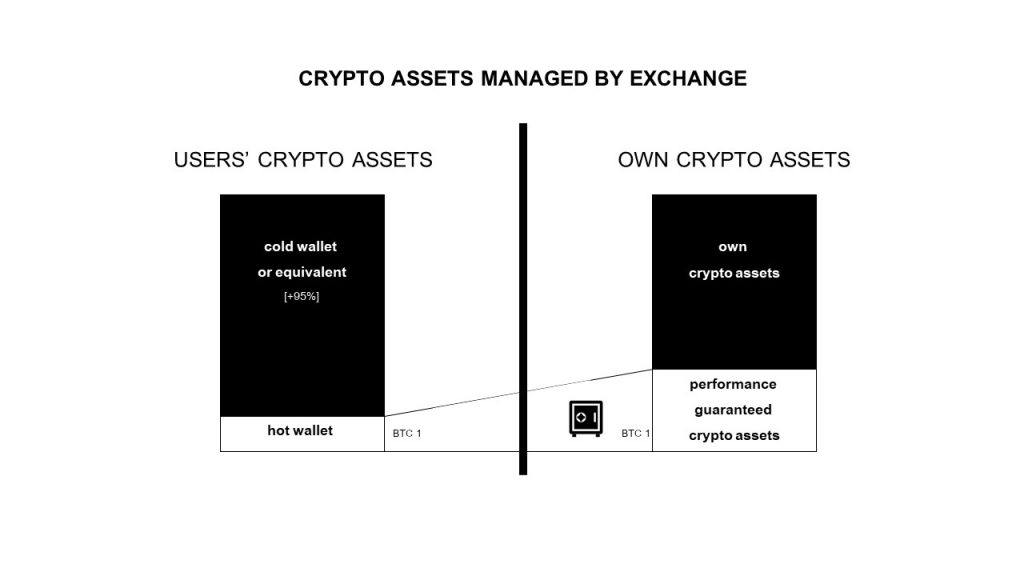

Custody Services

Under the new regulations, exchanges are generally required to hold 95 percent of their users’ funds in a cold wallet or secure them by means which provide a similar level of security. The remaining 5 percent can be stored in a hot wallet but must be fully backed by an exchange’s own funds.

It should be noted that in both cases, the exchange remains in full control over its users’ funds. A user is, therefore, generally able to withdraw his funds at any time. This even applies in cases similar to a bank run and must be borne in mind when preparing the terms and conditions for yield farming and staking services.

POS UNDER THE PSA

As shown above, PoS mechanisms come in different shapes and sizes. It is, therefore, necessary to analyze the design carefully when assessing the admissibility of staking services.

As much as the admissibility depends on the design of the respective consensus mechanism, it depends on the contractual arrangements in place. Both components and their interaction with each other must, therefore, be analyzed comprehensively. This applies in particular because the right contractual arrangements may neutralize some of the negative effects resulting from design choices.

Control Over Funds

The first thing to consider is who controls the staked funds. If it is the user, which is highly unlikely if not impossible in case of centralized exchanges, there are no concerns. The same is true if the funds are controlled and remain under the control of the exchange after being used for staking.

PoS

In most PoS models, a user must lock his tokens in a smart contract for staking. While the tokens are temporarily locked in the smart contract, i.e. the time they are used for staking and in some cases an additional period, they can generally be unlocked at any time.

The only one who can unlock the funds from the smart contract is the person controlling the private key corresponding to the address that was initially used to lock the funds in the smart contract. Except for slashing staked funds in case of misbehavior or excessive downtimes, the smart contract does not control the staked amount. In particular, it is not able to transfer the funds independently.

Since the funds remain under the control of an exchange, the situation is not different from any other situation where the funds are associated with an address controlled by an exchange.

DPoS

In the case of DPoS, the situation is generally not different from the situation described above. An exchange using funds for delegation services does not lose control over the funds at any time. This applies even if the funds are locked in a smart contract for delegation.

In some cases, namely the liquid PoS by tezos, the exchange must not even send a users’ funds to a smart contract. Instead, there are two keys – one for controlling the funds and another one for delegation. Unlike in other PoS models, it is therefore not even necessary to send the funds to a smart contract and withdraw them when a user wants to withdraw his funds from the exchange.

Hot Wallet VS Cold Wallet

Since the smart contracts used for staking do generally not control the locked funds, the situation is comparable to the situation where the funds are associated with an address controlled by the exchange. In both cases, the funds can only be transferred by the person controlling the private keys. If these keys are stored offline, the level of security is generally the same for funds locked in the smart contract and funds associated with an ordinary address. That being said, there is no reason to treat the two situations differently.

Liquidity Constraints

Most PoS consensus mechanisms require the user to lock funds into a smart contract. Even if the funds are unlocked, the holder of the private key may not receive the funds directly. An exchange staking its users’ funds may, therefore, not be able to respond to a withdrawal request immediately.

An exchange may either counter the delay by using its own funds or provide in its terms and conditions that there may be delays if a user also wants to use the exchange’s staking services. The terms may further lay out different periods for different protocols or simply use the longest period as a standard.

Economic Risks (Slashing)

Some PoS consensus mechanisms provide for slashing in case of misbehavior, excessive downtimes, or other violations of the protocol’s rules. In other words, the person violating the rules loses a certain amount of staked funds.

Where the economic risks and benefits are borne by the user, staking is more akin to investments than to deposits. Investment activities are, however, regulated under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) and require a different license. A crypto asset exchange license is not sufficient.

Crypto asset exchanges that do not have the necessary licenses must, therefore, implement measures to prevent users from bearing the economic risk of staking. One way to do so is by reconciling losses with the exchange’s own funds.

YIELD FARMING UNDER THE PSA

The legal considerations are generally the same for PoS and yield farming. In short, an exchange may not carry out activities where the users run the risk of making a loss.

Compared to staking, there is one fundamental difference, however. An exchange will lose control over the lent amount. The control over the asset is transferred to the lending protocol, which in turn lends the funds to other users.

In exchange for supplying the funds to the protocol, an exchange does, however, receive another token which represents an increasing share in the protocol’s funds. By transferring these tokens to the protocol, an exchange can generally redeem the locked funds from a lending protocol at any time. This applies at least if there is sufficient liquidity. In the case of illiquidity, an exchange may have to wait for a certain amount of time until the redemption may be completed. An exchange may bridge this time either by using its own funds or putting a contract in place that allows it to wait with the refund until there is sufficient liquidity on the respective market.

The private keys controlling the tokens issued by the protocol can be stored in a cold or hot wallet like any other key in possession of the exchange. Insofar, nothing different applies.

CONCLUSION

The PSA does not generally prohibit yield farming or staking services. This applies at least if the economic risks of staking or yield farming are not transferred to the user. It is also necessary to take a closer look at the respective PoS mechanism and adjust, where appropriate, the contractual documentation.

With respect to yield farming, it should be noted that DeFi lending has been prone to exploits by flashloans. Exchanges that wish to enter the space are therefore well advised to analyze potential attack vectors carefully.

Given the current vulnerabilities of DeFi protocols, we expect that only staking services will get more traction in the near future. Yield farming will, however, follow in the mid- to long term. If you want to discuss the technical and legal implementation of PoS and staking services, please feel free to contact us at any time.

[1] Staking Rewards, Trusted Data. Stakeable Assets., retrieved from https://www.stakingrewards.com/proof-of-stake (accessed on 03/08/2020).

[2] Unlike decentralized exchanges, centralized exchanges require users to transfer their funds to an address controlled by the exchange. The user does not have any control over the funds until he instructs the exchange to transfer the funds to an address specified by him.

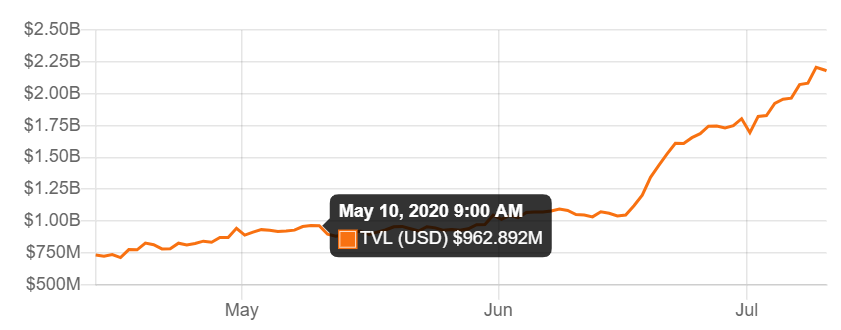

Mostly unrecognized by mainstream media, DeFi has gained increasing traction over the last few months. Large parts of its growth can be attributed to lending platforms such as Compound, Maker, and Aave, just to name a few. Broadly speaking, users of these platforms receive some form of interest in exchange for locking their assets into a smart contract, which in turn lends them to (other) users. Together with extrinsic rewards paid by these platforms, yields of up to 100 percent are currently possible. The process of optimizing yield through a combination of leverage and rewards is commonly referred to as yield farming and liquidity mining.

In this article, we will discuss the regulatory treatment of lending platforms under Japanese laws. Restrictions for users do not exist. In our next article, we will focus on the opportunities, Compound and other platforms provide to crypto asset exchanges in Japan, which currently face fierce competition and pressure under the new regulations.

The chart includes data from DEX, lending, derivatives, payments, and assets platforms.

1. The Concept

The basic concept of yield farming and liquidity mining is to generate passive income from crypto assets. Yield farmers and liquidity miners generally try to put their assets to maximum use by utilizing a combination of lending and borrowing techniques on one or more lending platforms. Apps such as Instadapp help users to bridge different protocols and to leverage the full potential of DeFi by automating large parts of the lending and borrowing activities.

To explain how yield farming and liquidity mining work, we will use Compound, one of the biggest and currently most used platforms, as an example.[1]

1.1 Lending

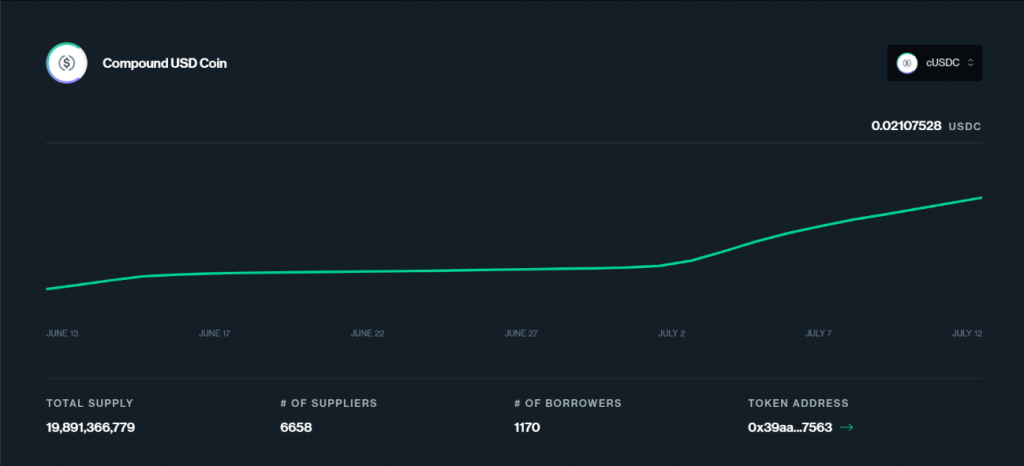

In order to earn a yield on Compound, users must lock their assets in a smart contract. In turn, the smart contract issues new tokens (cTokens) at a predefined exchange rate. These tokens allow the user to earn a yield over time and to use them as collateral when borrowing funds via the platform.

cTokens do not provide recurring revenue to their holders. Instead, they represent a share in a pool of assets that constantly grows due to borrowers’ interest payments. With the price of cTokens increasing relative to the locked assets, cTokens generate a yield when used to withdraw the locked assets. The actual amount depends on the compound interests calculated by the protocol based on market dynamics, namely supply and demand.

In addition to the compound yield, lenders currently receive COMP tokens. These tokens allow their holders to propose and vote on changes to the protocol and are actively traded on exchanges. Only with COMP tokens, the current yields are possible at all.

1.2 Borrowing

When borrowing funds via Compound, a user must deposit cTokens as collateral. The maximum amount a user can borrow depends on the collateral factor of the deposited asset. This factor is set by COMP token holders. The collateral factor is generally higher for liquid, high-cap assets and lower for illiquid, small-cap assets. The collateral factor of ETH, for example, is currently set at 0.7. A user supplying ETH 100 to the protocol, would therefore be able to borrow up ETH 70 worth of assets via Compound.[3]

Where a user’s borrowing balance exceeds his borrowing capacity due to outstanding interests, the value of collateral falling or the borrowed assets increasing in price, the collateral will be liquidated automatically at a discount to the current market price.

Like lenders, borrowers currently receive an external reward in the form of COMP tokens for using the Compound platform. Every day, approximately 2,880 COMP are distributed – 50 percent to lenders and 50 percent to borrowers.

2. Regulatory Environment

When analyzing the legal and regulatory environment for DeFi lending activities, it is necessary to break down the lending model into different components. First, it is necessary to analyze the tokens required for the protocol to work. In a second step, the activities involving each of the tokens must be analyzed in more detail. It should be noted, however, that it is not possible to view tokens and activities as separate components, but that it is necessary to consider the interaction between both for the analysis.

2.1 Legal Classification of the Tokens

Compound and other lending platforms involve a number of different tokens. In the case of Compound, these tokens are (i) ETH and ERC-20 tokens supplied to the protocol, (ii) cTokens which are issued in exchange for the tokens supplied, and (iii) COMP which is issued as a reward and which constitutes the protocol’s governance token.

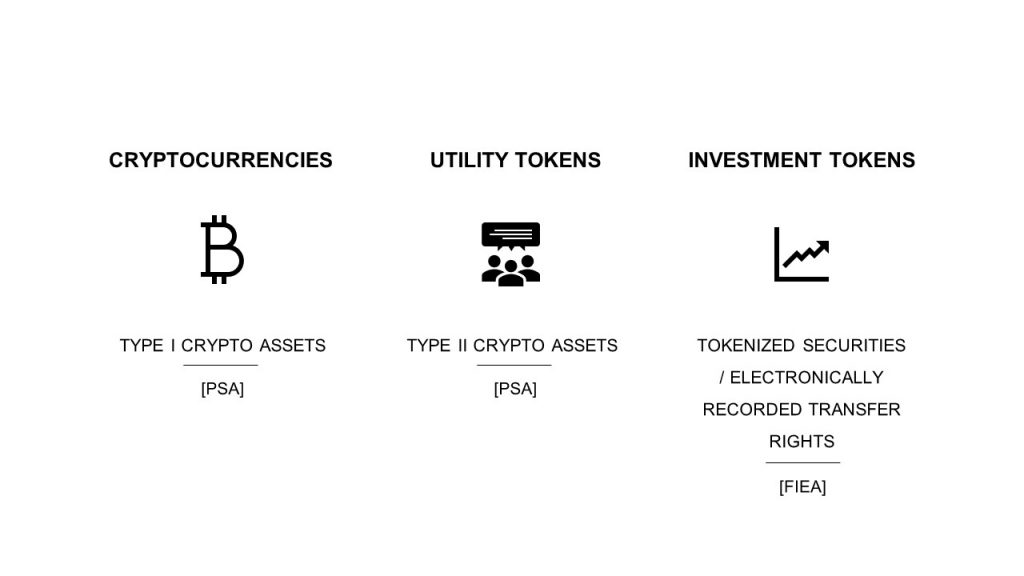

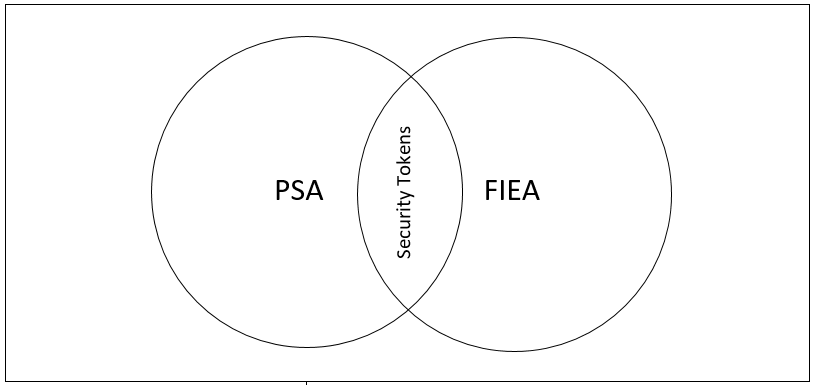

Under Japanese laws, tokens may either constitute crypto assets under the Payment Services Act (PSA) or electronically recorded transfer rights under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). Tokens neither covered by the definition of crypto assets nor electronically recorded transfer rights may not be regulated at all.

The PSA distinguishes between type I crypto assets and type II crypto assets. Type I crypto assets are proprietary values that can (i) be used for purchasing goods and services from unspecified persons, (ii) purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparties, (iii) and transferred electronically.

Type II crypto assets are property values that can (i) be mutually exchanged with unspecified persons for type I crypto assets and (ii) transferred electronically. Currency denominated assets such as fiat currencies and electronically recorded transfer rights are explicitly excluded from the definition of both type I and type II crypto assets.

The definition of electronically recorded transfer rights was added to the FIEA with the latest amendment. It covers electronically recorded values that represent type II securities which can be transferred electronically, and which do not have liquidity constraints.

2.1.1 ETH and ERC-20 Tokens

Currently, most platforms, including Compound, allow users to deposit ETH, certain ERC-20 utility tokens[4], and different kinds of stable coins.

ETH is a typical type I crypto asset. ERC-20 utility tokens generally constitute type II crypto assets as they can easily be exchanged with type I crypto assets. The same most likely applies to wrapped bitcoin as they are currently not used for payment and can only be exchanged with type I crypto assets.

For stable coins, the legal classification depends on their exact features and underlying model. The most prominent stable coins, such as USDT and USDC, are based on an IOU model. Each token is backed by one USD.[5] As a result, they are likely to fall under the definition of currency denominated assets and are thus excluded from the definition of crypto assets under the PSA. For more information on the classification of different stable coins, click here.

2.1.2 cTokens

cTokens represent a user’s balance in the Compound protocol. As the market earns interest, the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying assets. This raises questions as to whether cTokens represent beneficiary certificates in a money market fund (MMF) or interests in a collective investment scheme and therefore constitute electronically recorded transfer rights.

Beneficiary Certificates in an MMF

Traditionally MMFs are used as cash management vehicles for retail and institutional investors. Defining features are the payment of dividends, the fact that investors can redeem their certificates at any time, and the fact that MMFs seek to maintain a stable net asset value. The redemption of a substantial amount of beneficiary certificates may, however, result in a loss of liquidity and negatively affect the remaining certificates’ price.

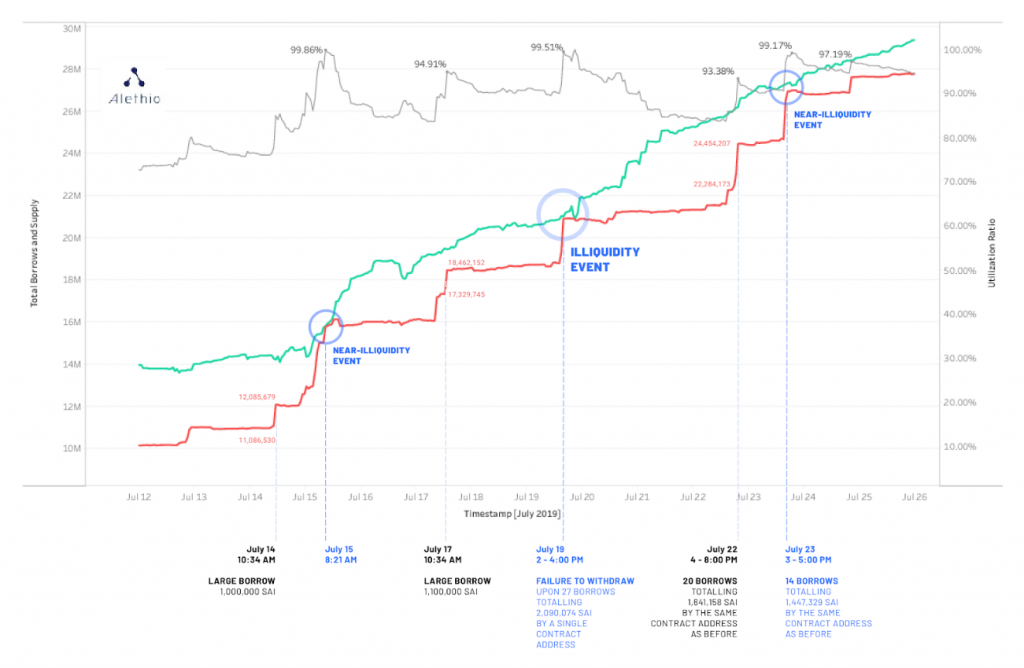

The risk of illiquidity also exists in the case of Compound and other DeFi protocols. As the following graphic shows, it may be even more pronounced than for traditional MMFs.

The green line indicates the total amount of SAI supplied, the red line the total amount of SAI borrowed, and the grey line the utilization ratio.

The difference between Compound and traditional MMFs is that a user’s yield is independent of profits generated by the protocol. Rather than calculating the yield after repayment of the borrowed loans, the protocol uses the prevailing interest rate for each interval when calculating the compound interest rate. Whether a loan is fully paid back at any point in time or not, is irrelevant

It is further worth noting that the Compound protocol does not constitute a legal entity that could act as a trust. The protocol is also not controlled by a legal entity that may otherwise be seen as a principal.

Interests in a Collective Investment Scheme

The definition of collective investment schemes in the FIEA[7] is intentionally broad and covers various arrangements that are used to pool money for investment purposes. Investors in a collective investment scheme are entitled to participate in the earnings a scheme generates but bear a business risk at the same time. If the scheme suffers a loss, investors in the scheme suffer a loss as well.

The argument that Compound and other DeFi platforms do not pay dividends can also be used with regard to collective investment schemes. Unlike investors in a collective investment scheme, holders of cTokens earn a yield irrespective of profits generated by the platform. The yield solely depends on the accrued interests over time and is calculated by using the interest rate on the respective markets for each block.

While there is an illiquidity risk, lenders should generally not make a loss when using Compound. This is due to the over-collateralization and auto-liquidation of loans where the balance of the collateral is insufficient to support the loan. If this promise holds true, the situation is fundamentally different from collective investment schemes where investors may actually suffer a loss.

It may further be argued that cTokens do not fall under the definition of interests in a collective investment scheme as they do not represent rights. Rights, by definition, require a counterparty. In the case of DeFi, a counterparty does not exist. Instead, assets are collected and distributed via smart contracts according to predefined rules on a factual basis. Whether the regulator will follow this argument remains to be seen. Yet, we believe that there is plenty of room to argue that cTokens and similar arrangements do not fall under the definition of collective investment schemes and do, therefore, not constitute electronically recorded transfer rights under the FIEA.

Type II Crypto Assets

Since cTokens can be transferred electronically and exchanged with other tokens, they represent type II crypto assets under the PSA. The fact that the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying asset does not lead to different results. This is because their value is only driven by market forces, namely supply and demand. The protocol merely ensures that the value of cTokens does not decrease relative to the underlying asset over time.

2.1.3 Governance Tokens

Governance tokens issued by the Compound protocol constitute type II crypto assets. They can be exchanged with other crypto assets but are not used for payment. The fact that governance tokens provide the user with voting rights is irrelevant for the legal classification in the absence of other features.

2.2 Legal Classification of Activities

2.2.1 Lending and Borrowing of Crypto Assets

The lending and borrowing of crypto assets are not regulated under Japanese laws. A banking license or money lending license is therefore not required.

2.2.2 Exchange with cTokens

The exchange of crypto assets is generally considered a crypto asset exchange business in Japan. This applies irrespective of whether the exchange is facilitated by a centralized exchange, a decentralized exchange (DEX),or another smart contract if there is a controller.

Whether the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA is not clear. Neither the PSA nor any subsidiary legislation contains a definition of exchange. Yet, there are good reasons to doubt that the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA and must, therefore, be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA).

cTokens are issued when a user supplies other tokens to the protocol. While this might look typical exchange of crypto assets, there is a fundamental difference. The user does not lose control over the initial amount deposited. cTokens more or less serve as a key to unlock the initial amount deposit and can be used at any time to do so – provided of course, there is sufficient liquidity. For typical exchanges, this possibility does not exist. The same applies to the exchange of cTokens for other crypto assets.

2.2.3 Issuance of Governance Tokens

The issuance of governance tokens is not an exchange business as well. While the issuance of tokens in exchange for liquidity, is sometimes compared with ICOs the key difference is that there is no payment of consideration for receiving the tokens. Instead, the tokens are issued as a subsidy by the platform without additional consideration. It is therefore more akin to an airdrop where an issuer aims to promote his platform. Also, in these cases, it is not necessary to register as a crypto asset exchange.

2.2.4 Locking of Tokens into Smart Contract

The definition of crypto asset exchange services also includes custody business. When tokens are locked into a smart contract, this may generally be considered custody under the PSA. It may however be argued that this does not apply where the smart contract creator does not have control over the contract. In these cases, only the user is able to unlock the supplied amount by transferring cTokens to the smart contract and to release the funds. The automatic liquidation function does not change this result as the protocol creator does not have control over the funds at any point of time.

Conclusion

While DeFi has become increasingly popular over the last few months, it has not been on the radar of Japanese regulators so far. The good news is that certain protocols and tokens will most likely not fall under the FIEA. This will hopefully allow DeFi to get some more traction on the Japanese market and allow exchanges to add DeFi to their services.

As so often, the devil is in the detail. Much depends on the structure of the overall arrangement and the token design. Existing projects that intend to enter the Japanese market are therefore well advised to analyze their protocol and token design carefully.[8] The same applies to crypto asset exchanges that intend to add further services in the future to become more attractive in an increasingly competitive market.

We will analyze the possibilities resulting from DeFi and PoS for exchanges in our next article. Stay with us.

DISCLAIMER

The DeFi protocols mentioned in this article, in particular Compound, are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the article, not all details of the protocol and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project. By no means, the explanations should be understood as a legal opinion regarding DeFi protocols mentioned in this article.

[1] According to DeFi Pulse, 28.03 percent of the USD 2.51 billion total value locked in DeFI is currently locked in Compound, DeFi Pulse, retrieved from https://defipulse.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[2] Compound, retrieved from https://compound.finance/ctokens (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[3] It is worth noting that a user’s collateral would immediately be liquidated to a certain extent with the first interest payment becoming due.

[4] For this paper, utility tokens are understood as tokens that give token holders access to an application or a service and which serve as a platform-internal currency.

[5] For USDT, the accounts have not been properly audited so far.

[6] Alethic, Illiquidity and Bank Run Risk in DeFi, retrieved from https://medium.com/alethio/overlooked-risk-illiquidity-and-bank-runs-on-compound-finance-5d6fc3922d0d (accessed 10 July 2020).

[7] Article 2(2)(v) FIEA.

[8] DeFi, by definition, does not necessarily involve a central entity controlling the project. It may, therefore, be difficult for the regulator to get hold of the persons behind the project. If a project aims to get more traction in the regulated space, there is however no way to cut some corners or to circumvent regulation altogether.

An overview of the latest amendment to the Japanese crypto regulations. The changes entered into force on May 1, 2020 and affect cryptocurrency exchanges, custodians, crypto derivatives, and security token offerings (STOs).

The following presentation provides a high level overview.

Crypto_Law_Amendment(JP)_200427

Crypto_Law_Amendment(EN)_200424

For a more detailed explanation please visit our article on digital assets.

Starting with Bitcoin in 2009, crypto assets have come a long way. Now, more than ten years later, the ecosystem is more diverse than ever, and bitcoin and other crypto assets are on the verge of becoming a new asset class. At the same time, blockchain technology has made significant progress and evolved from a pure state transition system to fully programmable networks. 2nd and 3rd generation networks allow other projects to build dApps on their platform and to deploy smart contracts to issue their own tokens. With the rise of these platforms, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), Initial Exchange Offerings (IEOs), and Security Token Offerings (STOs) have become a popular mechanism to raise funds. The flexibility offered by 2nd and 3rd generation networks also opened up new possibilities for more complex applications such as DeFi.

The potential of blockchain technology has also been recognized by governments around the globe. Experiencing pressure from projects such as Libra, some of them have intensified their research on central bank digital currencies and other blockchain applications.

While the industry is increasingly professionalized, major hacks exposed vulnerabilities in the existing infrastructure. Money laundering is another concern for policymakers. In view of these challenges and an increasingly diversified environment, the Japanese legislator amended the Japanese crypto regulations and published subsidiary legislation more recently. The changes are entering into force on May 1, 2020.

In this article, we take a closer look at the regulatory treatment of different digital assets, analyze the primary and secondary markets for them and provide an overview of different players in the industry, reaching from exchanges to liquidity providers and custodians.

Our article does not consider the current regulatory environment. For more information on the existing framework, please visit our older articles, which can be found here.

1. DIGITAL ASSETS

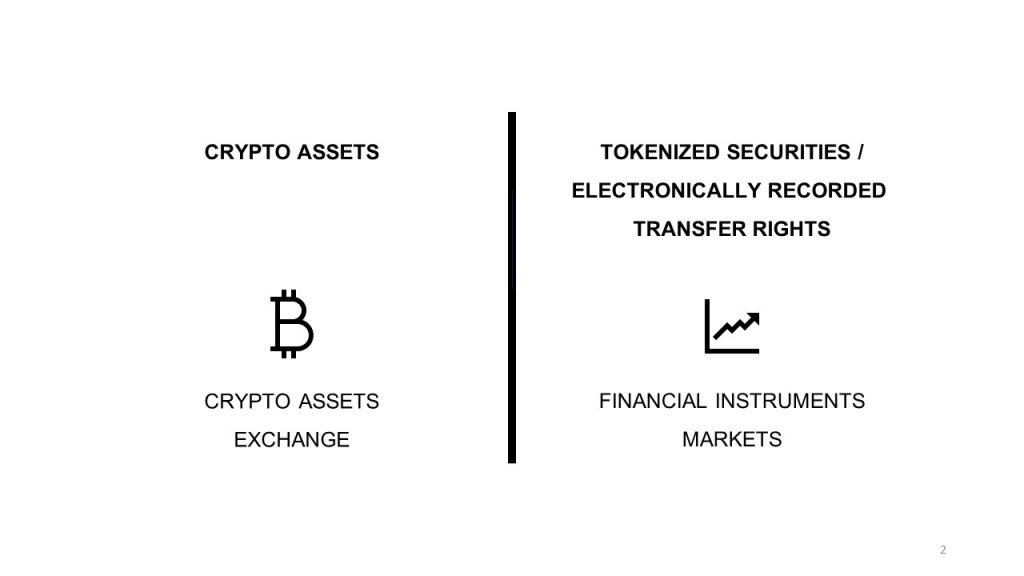

There is no general definition of digital assets under Japanese laws. Rather, the Payment Services Act (PSA) and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) define certain types of digital assets. The definitions are mutually exclusive and – seen as a whole – form a complete picture covering cryptocurrencies, utility tokens and investment tokens.[1] Non-fungible tokens (NFT) and stable coins[2] are not necessarily covered by the definitions in the PSA and the FIEA.

1.1 Crypto assets under the PSA

The PSA defines crypto assets exhaustively. Type I crypto assets are defined as property value that can be (i) used with unspecified persons for purchasing goods or services, (ii) purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparty, and (iii) transferred electronically.[3]

Type II crypto assets are property values that can be (i) mutually exchanged with type I crypto assets with unspecified persons acting as a counterparty and (ii) transferred electronically.[4]

Currency denominated assets and electronically recorded transfer rights as defined in the FIEA are explicitly excluded from the definition of crypto assets.[5]

Type I crypto assets: cryptocurrencies

Type II crypto assets: utility tokens

1.2 Electronically recorded transfer rights under the FIEA

For a better understanding of electronically recorded transfer rights, it is worth looking at the definition of securities under the FIEA. The FIEA contains a comprehensive list of securities and distinguishes between type I and type II securities. Type I securities are traditional securities such as bonds and stocks, which are generally perceived as being highly liquid.[6] Type II securities are, for example, units in a fund, beneficial interests in a trust, membership rights in a general partnership or limited partnership, and equity in limited liability companies.[7] These securities are generally much less liquid than type I securities and are therefore subject to lighter regulation. With the occurrence of tokenization, type II securities became, however – at least in theory – much more liquid. As a response, the legislator introduced electronically recorded transfer rights into the FIEA. These rights represent type II securities which are treated as type I securities.[8]

The FIEA defines electronically recorded transfer rights as (i) electronically recorded property values that (ii) represent type II securities and can be (iii) transferred by electronic means. In addition, (iv) there must not be any liquidity constraints or other circumstances specified by cabinet order.[9] Tokens that are sold to professional investors and for which the transferability is technically restricted, fall under the exemption of item (iv).[10]

Tokens representing type I securities are not covered by the definition of electronically recorded transfer rights and are therefore not excluded from the definition of crypto assets.[11] According to unofficial statements, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) considers type I securities as currency denominated assets, however, which are excluded from the definition of crypto assets as well.

1.3 Crypto derivatives

Crypto derivatives such as CFDs, futures, options, and swaps have become increasingly popular more recently. Some of them are said to legitimize crypto assets as a whole and to provide additional liquidity to crypto markets. In Japan, crypto derivatives account for roughly 90 percent of the total crypto trading volume.[12]

Crypto assets as defined in section 1.1 above are financial instruments within the meaning of the FIEA.[13] Derivatives using crypto assets as underlying or crypto asset indices as reference indices are therefore covered by the FIEA.[14] The FIEA distinguishes between derivatives transactions conducted on financial instruments market and OTC derivatives transactions.

Market derivatives transactions include[15]

- futures

- index futures

- options

- swaps

OTC derivatives transactions include[16]

- forward contracts

- index forward contracts

- options

- index options

- swaps

Excursion – Physical Settlement and Crypto Asset Exchange License

Crypto assets are deemed money under certain provisions of the FIEA.[17] Derivatives transactions may therefore be settled in cash or physically, i.e. by using crypto assets for settlement. The guidelines for crypto asset exchanges explicitly state that a crypto asset exchange license is not required in such cases.[18] In cases of margin trading where crypto assets are taken as collateral, something different might apply.

2. PRIMARY MARKETS

Tokens are often used for fundraising purposes. In this section, we take a closer look at fundraising via initial coin offerings (ICOs), initial exchange offerings (IEOs), and security token offerings (STOs).

2.1 Utility tokens

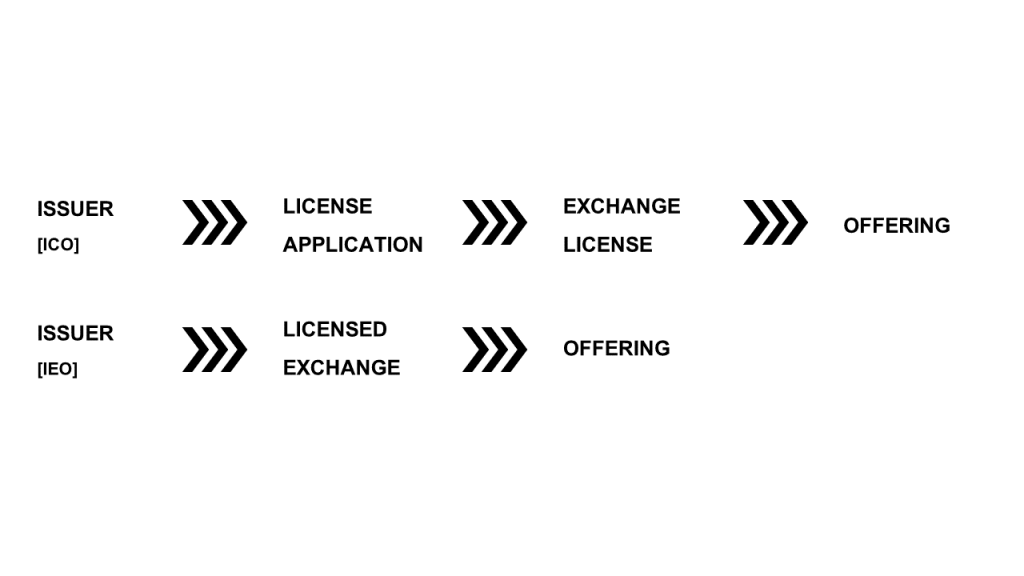

The offering of utility tokens for fundraising purposes is commonly known as ICO. Under the PSA, the offering of new tokens in exchange for fiat or cryptocurrencies is considered a crypto asset exchange service.[19] An issuer must therefore either register as a crypto asset exchange service provider[20] or sell his tokens via one of the registered exchanges. In the latter case, the exchange may either act as an intermediary or buy and sell the tokens on its own account.[21]

Excursion – Registration as crypto asset exchange

To register as a crypto asset exchange, companies must meet certain criteria. Local companies must be incorporated as a stock company[22] and have a minimum capital of JPY 10 million[23]. An exchange must further ensure that its net assets do not fall below the amount of users’ funds that are stored in a hot wallet.[24]

Aside from this, crypto asset exchanges must implement corporate governance and security systems that ensure fair dealing on the exchange and reduce operational risks.[25] The latter includes the separation of funds – both for crypto assets[26] and fiat currencies[27] – and the proper management of users’ funds held by the exchange (for more details, see section 4.1 below). Crypto asset exchanges violating their obligations under the PSA are subject to fines of up to JPY 3 million.[28]

While foreign crypto asset exchanges are generally able to register and operate in Japan, none of the 23 registered exchanges is currently a foreign exchange.[29]

2.1.1 Self-offering

Under the ICO regulations of the Japan Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA), an issuer who has successfully applied for a crypto asset exchange license must analyze its internal control and the feasibility of the target business comprehensively before launching its ICO.[30] The analysis must be based on certain documents, including the issuer’s financial statements, material agreements, business plan, whitepaper, and other documents deemed necessary by the issuer.[31] The results of the analysis must be submitted to the JVCEA for final review.[32] Only if the JVCEA does not raise any objections, the issuer may launch its ICO in Japan[33] after giving notice to the FSA[34].

When selling tokens to the broader public, an issuer must disclose a wide variety of information to the public in order to allow investors to make an informed decision. This includes among others:[35]

- information on the issuer

- information on the tokens and the token sale (incl. pricing information, incentives, sales period, token allocation, caps, future distributions)

- information on the use and the accounting treatment of the raised funds

- information on the project

- governing law and jurisdiction

Once the ICO is completed, the issuer must provide token holders with sales data, including information on the number of tokens issued and the total amount collected.[36] Token issuers are further subject to ongoing disclosure and must publish data about the status of the project and market value of the tokens at regular intervals.[37] This generally applies for a period of five years unless the protection of users is not compromised, and the issuer has informed the JVCEA.[38]

An issuer may not use the raised funds for any other purpose than disclosed to investors during the ICO[39] and must manage them separately from its other funds[40]. The private key controlling the raised funds must generally be stored offline.[41] The issuer must further establish an internal control system to prevent the misappropriation of funds by its officers and employees or the theft by third parties.[42]

2.1.2 IEO

Registered exchanges that allow other projects to launch their token offerings via their exchange must implement internal control systems to safeguard investors from investing in projects which are not feasible or an outright scam.[43] At the same time, they must ensure that the token issuer has systems in place to prevent inappropriate solicitation of the token sale or the misappropriation of funds.[44]

When assessing whether a token offering can be launched via its platform, an exchange must consider the issuer’s financial situation. To do so, an exchange must review the financial statements of the token issuer and, if possible, conduct a hearing with a certified accounting or auditing firm.[45] The sales price of the newly issued tokens must be determined in accordance with reasonable valuation methods (e.g. surveys on investment demand).[46] Registered exchanges must also ensure that the raised funds do not exceed the amount which is determined in the business plan of the issuer.[47] The results of the overall assessment must be submitted to the JVCEA for final review.[48] If the JVCEA finds that the offering is not feasible, the exchange must not proceed.[49]

To ensure that the trading of tokens is safe, exchanges must audit the smart contract and the blockchain protocol before launching the token sale.[50] The duty to ensure safety does, however, not end with the token sale. Rather, exchanges are required to monitor the system on an ongoing basis and report vulnerabilities to the JVCEA.[51]

Before offering new tokens on their platform, cryptocurrency exchanges must further publish certain information on their homepage. This information is largely identical to the information indicated in section 2.1.1.[52] Following the offering, the cryptocurrency exchange must ensure that the issuer properly maintains the internal control systems and disclosure mechanisms.[53] This does not apply if five years have passed since the offering or where the exchange has informed the JVCEA that investor protection is not compromised if compliance is no longer monitored by the exchange.[54]

Note: If an issuer actively engages in the token sale, this might be considered a crypto asset exchange service by the issuer and trigger registration requirements under the PSA despite selling the tokens via a registered exchange.[55] Whether this is the case must be determined on a case-by-case basis considering the degree of engagement and other factors.

2.2 Security tokens

The solicitation of an offer to sell securities in Japan is generally regulated under the FIEA. The term is understood broadly and covers any communication which allows investors to decide whether to purchase or subscribe for the offered securities. While there is no bright-line test, providing information on the terms of an offering is a clear indication of solicitation. As a rule of thumb, the more granular the information, the more likely it is that the marketing is considered a solicitation. Offers via the internet are generally considered a solicitation to invest in securities if they are made through a website that is publicly accessible. The use of the Japanese language is not necessarily required. Only where investors from Japan are effectively excluded from participating in the offer, for example, by geo-blocking or a KYC-process, an offering is not considered a solicitation of an offer to sell securities in Japan. A disclaimer, according to which Japanese investors are excluded from the offer, is not sufficient on its own but may, in combination with other measures, prevent the FIEA to apply.

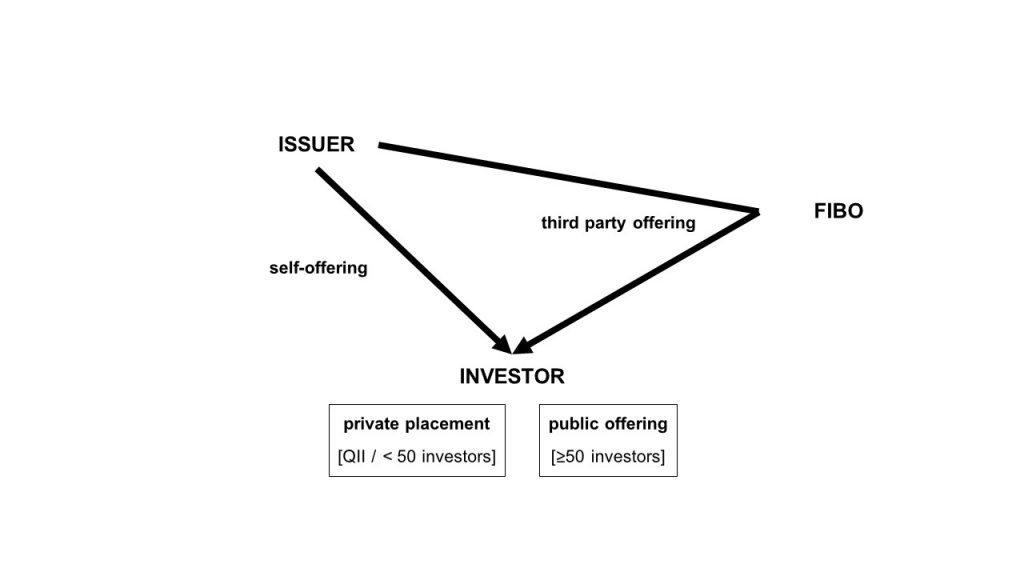

The FIEA distinguishes between public offerings and private placements, self-offerings, and offerings via intermediaries.

2.2.1 Public Offering

The offering of tokenized type I securities and electronically recorded transfer rights is considered a public offering if the tokens are offered to 50 or more investors.[56] Qualified institutional investors (QII) and professional investors as defined in the following section, are not considered when assessing the number of investors.

Public offerings with a total issue price of JPY 100 million (~ USD 915,000) or more must be registered with the FSA[57] and accompanied by a prospectus[58].

2.2.2 Private Placement

Offerings via private placements must not be registered with the FSA. Under the FIEA, the following offers are considered private placements[59]:

- offers to QII only where the transfer to persons other than QII is unlikely

- offers to professional investors only which satisfy all of the following requirements

- solicited party is not the state, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), or a QII

- solicitation by a Financial Instruments Business Operator (FIBO) on its own behalf or on behalf of a client

- transfer to persons other than professional investors is unlikely

3. offers to a small number of investors (< 50)

The definition of QIIs is rather extensive and consists of a long list of examples.[60] The list includes investment corporations, venture capital companies with a stated capital of JPY 500 million or more*, investment limited partnerships as well as special purpose companies*, other legal persons* and individuals* holding securities of at least JPY 1 billion.

Professional investors within the meaning of the FIEA are QIIs, the state, the BoJ, investor protection funds, and other corporations specified by cabinet order. The latter includes among others foreign corporations, specific purpose companies, and listed companies.

Tokens acquired in a private placement by QII or professional investors may not be resold to persons other than QII or professional investors as the case may be. If the tokens are resold in violation of the restrictions on resale, the issuer must file a registration statement with the FSA. This does not apply if the tokens are sold to a small number of investors and are subsequently resold by the initial investors to more than 49 persons.

2.2.3 Self-Offering

Companies selling their own tokens in a private placement or public offering do generally not have to register as a FIBO. This applies to both the offering of tokenized type I securities and the offering of electronically recorded transfer rights.

Only where the tokens represent beneficial interests in a (foreign) investment trust, (foreign) mortgage securities, units in (foreign) collective investment schemes, or where another case explicitly mentioned in the FIEA applies, the issuer must register as type II FIBO.[61] The registration requirements apply irrespective of whether the offering is a public offering or a private placement.

2.2.4 Third-Party Offerings

Intermediaries who are engaging in the offering of security tokens must register as a type I FIBO under the FIEA.[62]

Tokenized Type I Securities: cryptocurrencies

Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights: utility tokens

Excursion – Other laws

Token issuers must not only comply with the PSA or the FIEA but also with other laws and regulations. The applicable laws do not only depend on the features assigned to a token but also on the way the tokens are distributed. Certain laws may contain form requirements (e.g. physical form), which must be carefully considered when structuring the token and offering. As a general rule, it is however possible to tokenize most assets, including private shares. This topic will be covered in more detail in another article.

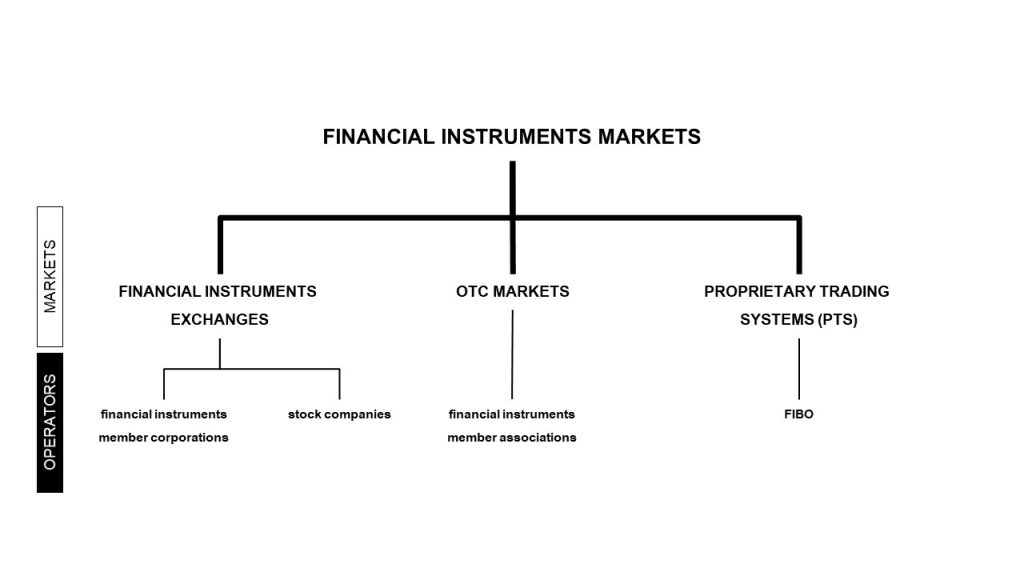

3. SECONDARY MARKETS

Similar to the offering of tokens on the primary market, the trading on the secondary market is subject to different laws depending on whether the token is a crypto asset under the PSA or a tokenized security/electronically recorded transfer right under the FIEA. Crypto asset exchanges licensed under the PSA may not trade security tokens and vice versa.

In this section, we take a closer look at the secondary markets and other key players supporting the trading infrastructure.

3.1 Utility tokens

3.1.1 Crypto Asset Exchanges

Under the PSA crypto asset exchanges and other companies providing crypto asset exchange services must register as crypto asset exchange service providers with the FSA.[63] Crypto asset exchange services are defined broadly and cover the following activities, provided they are carried out as a business:

- purchase and sale of crypto assets or exchange with other crypto assets

- intermediary, brokerage or agency services for the purchase and sale of crypto assets or exchange with other crypto assets

- custody services for crypto assets[64]

Given the broad definition of crypto asset exchange services, not only crypto asset exchanges must register with the FSA but also other service providers engaging in crypto-related activities (for custody services see section 4.1 below).

Crypto asset exchanges must implement corporate governance and security systems that ensure fair dealing on the exchange and reduce operational risks. [65] This includes among others to

- establish and maintain a business management system

- comply with AML/CFT regulations

- eliminate relationships with anti-social forces

- ensure the protection of customers and their funds (e.g. segregation of funds, storing funds in cold wallets, and retaining own funds equivalent to the users’ funds held in a hot wallet)

- implement and maintain an information security management system

- prepare, submit, and maintain records related to crypto asset exchange services

- prohibit misleading advertisement and advertisement of speculative trading

- prohibit and report unfair trading practices (e.g. market manipulation)

- make prior notification to the FSA in case of changes (e.g. listing of new tokens, change of scope of crypto asset exchange services)

This list is not exhaustive, and further obligations arise under subsidiary legislation and self-regulation imposed by the Japanese Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA). The self-regulation rules by the JVCEA consistently extend existing regulations and specify in greater detail the obligations under the PSA and AML/CFT regulations.

Crypto asset exchanges and other service providers registered as crypto asset exchange service providers must not engage in activities related to security tokens. These activities are exclusively subject to the FIEA and require additional registrations/licenses.

Excursion: Listing of new tokens

Each token must be analyzed in detail before listing. Where a token violates laws or is likely to be used for criminal activities (incl. money laundering), it must not be listed.[66] This applies in particular for privacy coins for which transactions are anonymous or extremely difficult to track. The results of the analysis must be reported to the board of directors and eventually to the JVCEA.[67] In cases in which the JVCEA does not approve the listing, the respective token must not be listed.[68] The listing of the new token must further be notified to the FSA prior to the token being listed.[69]

Excursion: Margin trading

Crypto asset exchanges providing leverage must inform their users about the risks of margin trading, circuit breakers (if any), as well as the deadline and modalities of repayment.[70] For retail investors, the leverage must not exceed 2x.[71] For corporate clients, there is no fixed maximum leverage. Instead, the ratio may be determined independently by the respective exchange based on a quantitative calculation model or by the JVCEA.[72] Crypto asset exchanges that do not wish to use these ratios may alternatively use the standard leverage of 2x for corporate clients as well.[73] Security deposits may be paid both in fiat and crypto assets. The amount required as a security deposit is calculated each business day.[74] In case of deficiencies, additional payments must be made within 48 hours from the time detecting the deficiency.[75]

Crypto asset exchanges lending fiat to their users must additionally apply for a money lending license under the Money Lending Business Act.[76] Exchanges lending crypto assets do not have to apply for such license.

3.1.2 OTC trading

Given the broad definition of crypto asset exchange services, OTC desks generally seem to be regulated under the PSA at first sight. This applies to both principal desks and agency desks. A closer look at the definition of crypto asset exchange services reveals however, that this is not necessarily the case.

Principal desks: Principal desks buy and sell crypto assets in their own name and on their own account and become counterparty to each transaction. Exchanging crypto assets into fiat currencies and vice versa generally falls under buying and selling of crypto assets as defined in the PSA. The same is true for exchanging crypto assets with other crypto assets.

Agency desks: Agency desks do not become a counterparty to transactions. Rather they act as pure intermediaries and broker deals on behalf of their clients. Such activities constitute intermediary services that are generally covered by the PSA.