Category Archives: Uncategorized

I. Introduction

I’ve recently become obsessed with visiting the Osaka Kansai Expo. Recently, I received an invitation from a company where I serve as an external director to visit the “Future of Life” pavilion (official website: https://expo2025future-of-life.com/en/) by Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro, who is renowned for his work with androids. This experience made me deeply contemplate legal issues.

While this might be a slight spoiler, the exhibition presents a future where humans can become androids. It features a story of a grandmother and granddaughter who are close to each other. As the grandmother’s health deteriorates, she faces a choice: to die naturally or to continue living through androidization. The pavilion also features numerous other androids, creating an exhibition that makes visitors contemplate what “life” truly means. I should note that while I have visited over 40 pavilions so far, the “Future of Life Pavilion” is particularly recommended among them!

This raised a legal question for me as a lawyer. If humans could transfer their consciousness and memories to androids and “continue living” for 100, 500, or even 1,000 years beyond their biological lifespan, what stance should the law take? Specifically, can we legally treat the original human and their post-androidization existence as the same legal person?

An android gazing at itself in a mirror – can it truly be called “the former me”?

II. An android gazing at itself in a mirror – can it truly be called “the former me”?

Under the laws of most countries today, a person acquires rights at birth and loses them upon death. This fundamental principle of “biological death = extinction of legal personality” has been the foundation of legal systems worldwide for hundreds of years.

However, if technology enables consciousness and memories to be electronically preserved and transplanted into a different body (an android), this principle would face fundamental reconsideration. How should the law treat an existence that is biologically dead but whose personality and memories continue?

Note: This paper discusses androidization through digital transfer of consciousness and memory, not physical brain transplantation. It also distinguishes from cyborgization (replacing parts of living organisms with machines) and deals with complete personality transfer to an artificial body.

III. Four Legal Approaches

Legal approaches to this problem can be broadly divided into four categories:

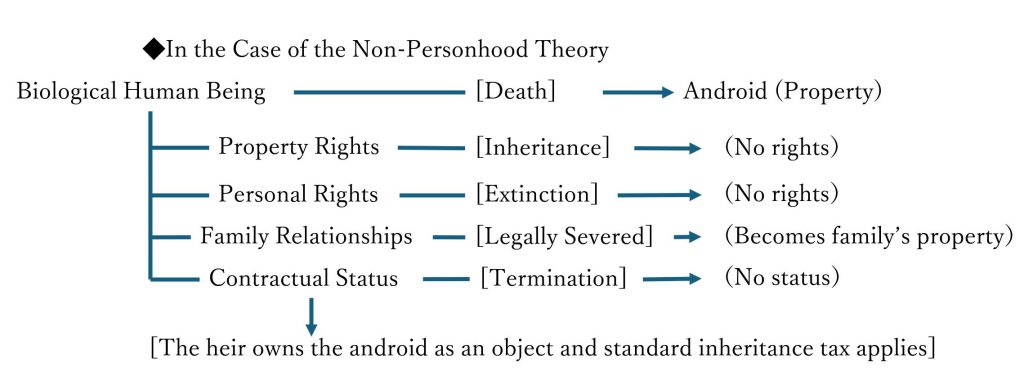

(i) Non-Personality Theory

This position treats the android as a “thing” without legal capacity once the physical body perishes and legal personality ends. From the standpoint of current law, this would basically be the prevailing view.

The android would be owned by heirs as inherited property, and the original human’s rights and obligations would be processed through normal inheritance procedures. In this case, the inheriting grandchild would own grandmother’s android as a “thing,” making it legally possible to sell it on marketplace apps or dispose of it as bulky waste – a result that borders on dark humor.

While legal stability would be maintained, the motivation to choose androidization would be significantly undermined. Few people would actively desire androidization if they might be treated as “things” subject to sale or disposal. Moreover, since they would lose all property rights and contractual status, they would be completely severed from the social positions and relationships they had built.

Is grandmother just a “thing”?

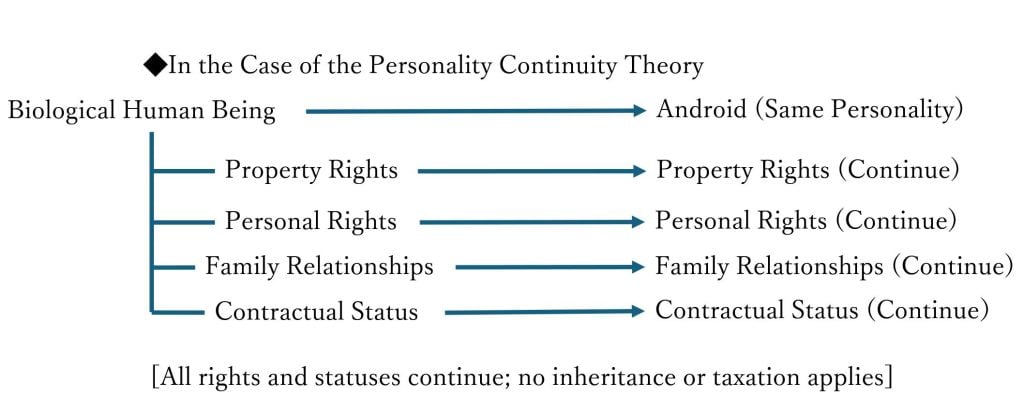

(ii) Personality Continuity Theory

This position emphasizes the continuity of memory, personality, and self-consciousness, treating the android as the same legal subject as the original human. In this case, property rights, family relationships, and contractual status would all be inherited as-is, and the person would be treated as “living” in the family registry.

While this would be the most desirable outcome for the individual, the impact on the entire legal system would be enormous.

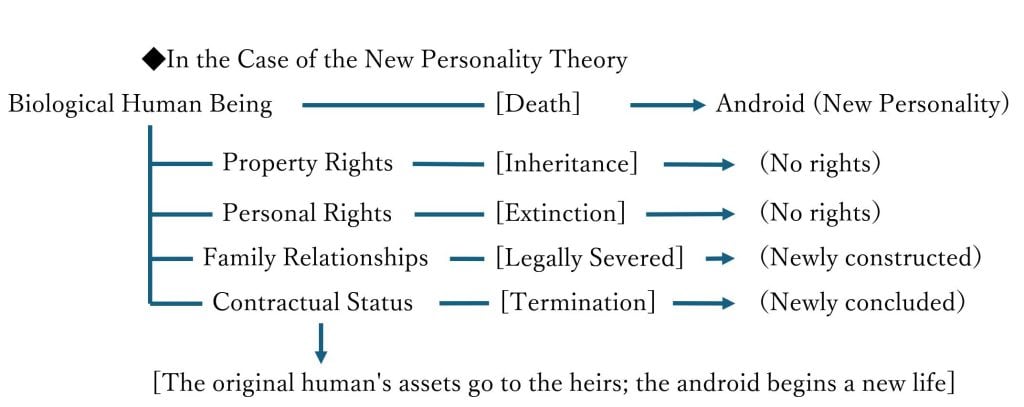

(iii) New Personality Theory

This position recognizes personality in androids, but the android is registered as a completely new legal subject, while the original human’s rights and obligations are processed through normal inheritance procedures.

From this standpoint, the android would begin a new life from zero as a “newly born adult.” While freed from past entanglements, they would also lose the human relationships and social status they had built.

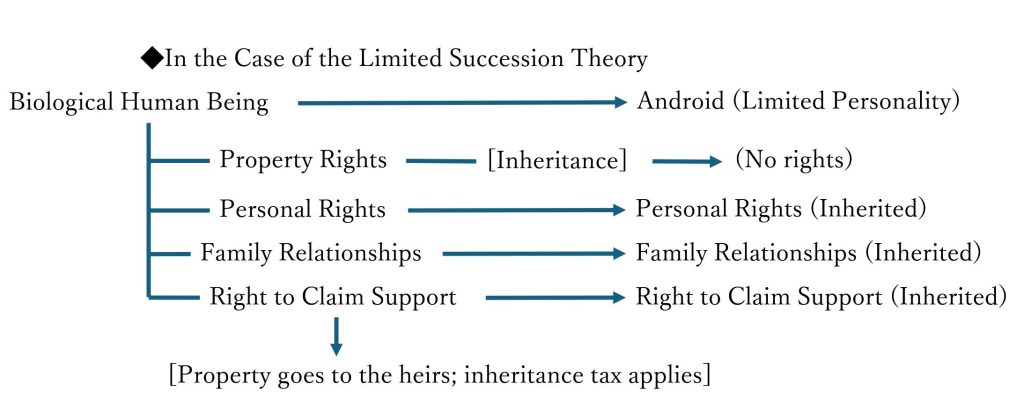

(iv) Limited Succession Theory

This is a compromise position that allows succession of only certain rights through special legislation. For example, a system could be designed where personal rights and family relationships are inherited, but property rights go through inheritance procedures.

Specifically, personal rights such as name rights and portrait rights, status relationships as spouse or parent-child, and support claim rights would be recognized for succession, while property rights such as real estate ownership, stocks, and deposits would still require traditional inheritance procedures.

The significance of this Limited Succession Theory lies in legally protecting the emotional connections of families and personal identity while ensuring the stability of socioeconomic systems. It can legally guarantee, albeit limitedly, the continuity of human relationships that would be lost through complete severance.

Comparison of Legal Positions on Androidization

| Item | Non-Personality Theory | Personality Continuity Theory | New Personality Theory | Limited Succession Theory |

| Basic Concept | Personality ends with physical body demise, treated as a property | Emphasizes continuity of memory and personality | Grants personality as new legal subject | Certain rights only succeed through special law |

| Legal Status | No legal capacity (treated as property) | Continues as same personality | Newly created legal person | Limited rights subject |

| Property Rights | Processed through inheritance | All succeeded | Processed through inheritance | Goes through inheritance procedures |

| Personal Rights (name, portrait, etc.) | No succession | All succeeded | Newly acquired | Partially inheritable |

| Family Relations | Treated as family asse | Continues | Newly established | Continues |

| Family Registry Treatment | Death certificate filed, registered as property | Continues as living | New birth certificate | Special registration system |

| Inheritance Tax | Taxed normally | Not taxed | Taxed normally | Only property portion taxed |

| Benefits to Individual | Minimal (treated as property) | Maximum (all rights continue) | Small (new life but no rights) | Moderate (personal rights protected) |

| Social Impact |

Minimal (maintains current system) | Enormous (fundamental system change) | Moderate (family registry expansion) | Moderate (partial system change) |

| Feasibility | Easiest (current law as-is) | Difficult (fundamental legal reform) | Somewhat difficult (new system creation) | Moderate (special legislation) |

IV. Legal Chaos Brought by Super-Longevity Society

Would current legal systems function when androidization allows humans to live for 1,000 years? If androidization achieves effective immortality, many current legal systems could become dysfunctional.

(i) Impact on Civil Law

The inheritance system would fundamentally change. If people don’t die, inheritance doesn’t occur. As a result, assets like real estate and stocks would be permanently occupied by the same individuals, severely impeding social fluidity.

Contract relationships would also become abnormally long-term, potentially causing rigidity in the entire socioeconomic system.

(ii) Impact on Family Law

If one spouse becomes an android, what happens to the marriage relationship? Since the androidized spouse is legally “living,” the other spouse’s remarriage would raise bigamy issues.

Parent-child relationships would also become complex. The relationship between androidized parents and subsequently born children, and the scope of support obligations across generations – these are problems traditional family law never anticipated.

(iii) Impact on Criminal Law

The penal system would require fundamental revision. The meaning of life imprisonment would be relativized, and consistency with statute of limitations would become problematic. The concept of “rehabilitation potential,” one of the foundations of punishment, would also change significantly when premised on lifespans of hundreds of years.

V. Impact on Political and Social Systems

Would democracy remain viable if immortal beings continued to hold political power? The impact extends beyond legal issues to affect democratic institutions themselves.

In a society where only the wealthy can choose androidization, they would continue exercising political and economic influence for hundreds of years. An “immortal elite class” with voting and candidacy rights could monopolize decision-making, impeding social renewal through generational change. As Piketty pointed out that “the return on capital exceeds economic growth rate (r > g),” the phenomenon of wealth accumulation and expansion could be further accelerated by the perpetual androidization of the ultra-wealthy.

Pension systems, healthcare systems, and education systems – current social security systems are designed based on average human lifespan. These systems would also require fundamental revision.

[Column: The Multiple Android Problem – Who is the “Real” One?]As technology advances, multiple androids could potentially be created simultaneously from one person’s consciousness and memory. For example, suppose there exists “Android 1” created from Person A’s memory transfer and “Android 2” later restored from a backup. Furthermore, if biological Person A is still alive, we would have a three-way coexistence of “Person A + Android 1 + Android 2.” In such cases, the following legal problems would arise: ◆ Identification of Rights Holders

◆ Property and Contractual Confusion

◆ Overlapping Family Relationships

Such problems could fundamentally shake legal systems in a future where single personalities can be digitally “replicated.” While current law doesn’t anticipate such situations, “uniqueness guarantee,” “identity authentication,” and “centralized management of digital personalities” might be required as premises for future system design. |

“I’m the real one!”

VI. Possibilities for Legal System Design

How should our legal system evolve to address such a future society?

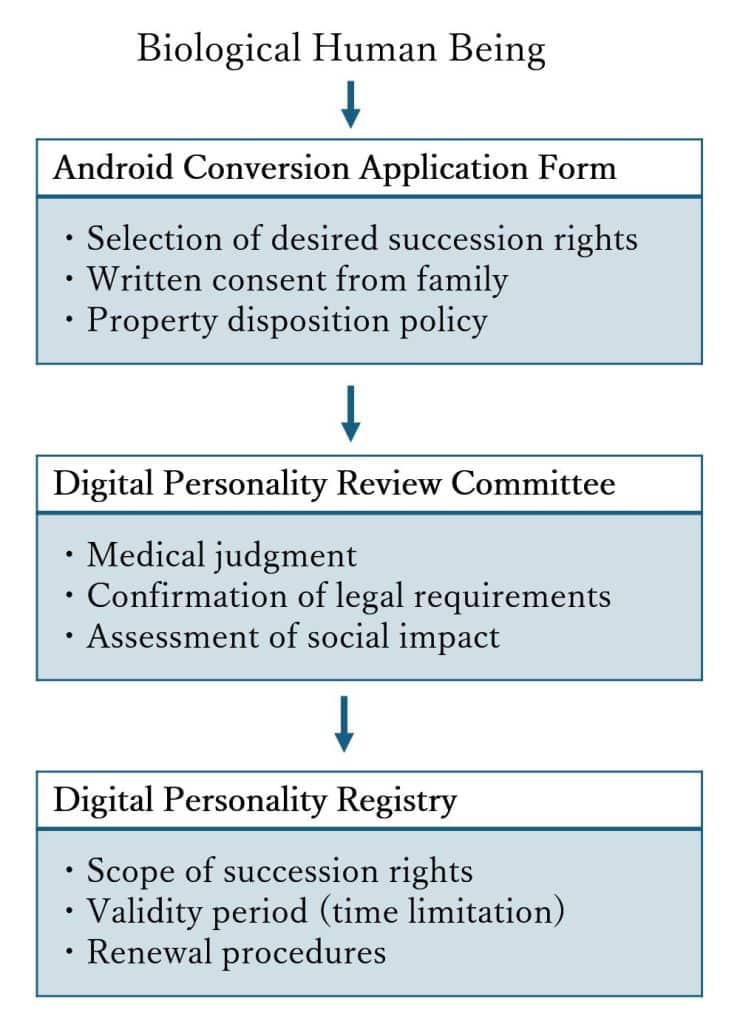

(i) Digital Personality Registration System

This would establish a new family registry system specifically for androids, recognizing personality succession based on clear expressions of intent made during one’s lifetime. The scope of inheritable rights would be clearly defined in written law to ensure legal predictability.

Digital Personality Registration System Process Flow

(ii) Time-Limited Personality System

To ensure social fluidity, this system would limit personality succession to a specific period (for example, 50 years). After the period expires, mandatory status transfer would occur, legally guaranteeing generational change.

(iii) Hybrid Legal Personality System

This would create “Android Corporations” as entities between individuals and corporations, recognizing limited legal personalities that inherit only specific rights. This system aims to balance continuity of social roles with legal stability.

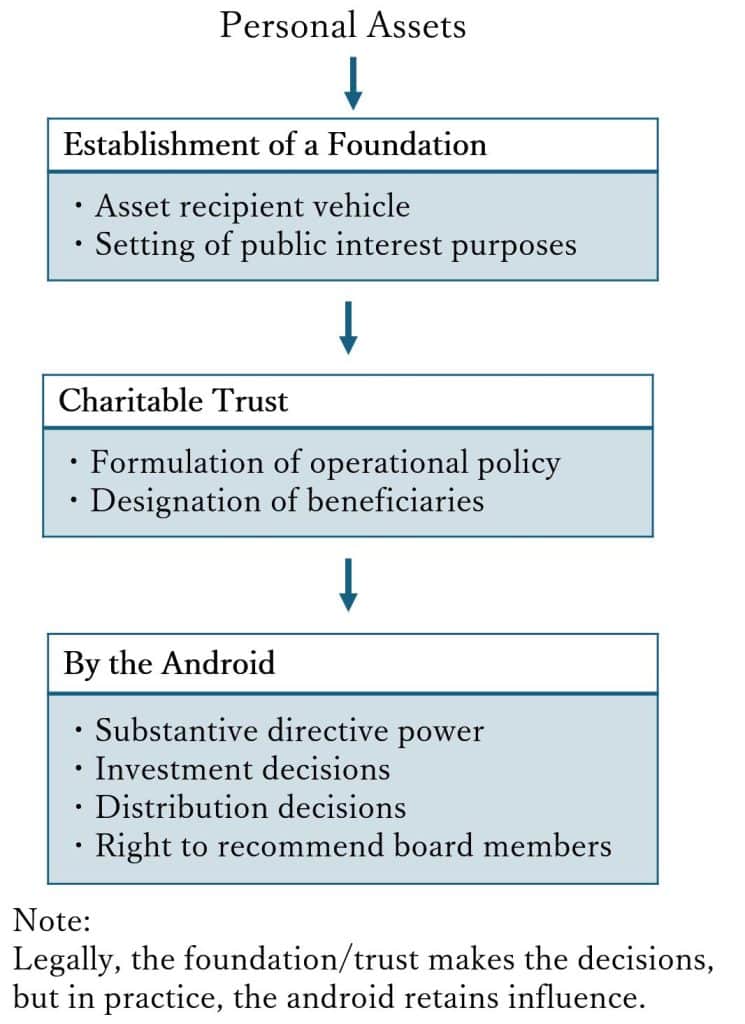

(iv) Utilization of Trust and Corporate Schemes

As background, I previously worked as a financial lawyer creating Charitable Trusts in jurisdictions like the Cayman Islands and establishing corporations with no shareholders. Even if android personality rights were restricted, it might be possible to create a system where companies and foundations are established, all assets transferred to them, and the android embodiment directs these entities. This could potentially enable survival while maintaining assets for 1,000 or even 2,000 years.

By applying such existing legal schemes, we could potentially achieve substantial rights succession after androidization. We may need to consider whether such schemes should be prohibited.

Android Substantial Rights Holding Structure (Cayman Islands-type Scheme Example)

[Column: Can AI Be Granted Legal Personality? – Legal Status of “Bodiless Intelligence”]When discussing personality succession through androidization, another intriguing question emerges: “Can pure AI (artificial intelligence) be granted legal personality?” ◆ However, Could This Apply to “Memory-Holding AI”?Meanwhile, systems like “memorial AI” that learns a person’s voice, speech patterns, and values, or “Digital Executor” AI that realizes posthumous wishes, are progressing as real technological challenges. ◆ Direction for Legal Organization

Thus, AI and androids are fundamentally different in their “nature of personality” and “legal roles.” While this paper focuses on “how to inherit personality,” the separate question of “whether to grant personality to new intelligence” will also be an unavoidable issue in future legal system design. |

VII. Impact on Legal Practice

If such technology becomes reality, significant changes will be required in legal practice. New legal service demands will emerge, including preparation of lifetime intent documents regarding androidization, establishment of digital asset management and succession contracts, and support for family consensus building.

The legal profession will also urgently need to establish ethical codes responding to new technologies and continuous training systems.

Humans as Digital Information

VIII. Conclusion

What I felt from viewing Professor Ishiguro’s exhibition was the magnitude of technology’s impact on legal systems. While the issue of personality succession through androidization remains in the realm of thought experiments at present, considering the speed of technological development, this is an area where the legal profession should begin discussions early.

Legal studies must find answers to fundamental questions: What is humanity? What is personality? What is the individual’s position in society? In an era where technology transforms society, new challenges await legal professionals.

Note: This paper represents the author’s personal views as part of thought organization and does not predict or guarantee future legal systems. While Saito is somewhat positive about androidization, there is absolutely no intention to encourage readers to “please become androids!”

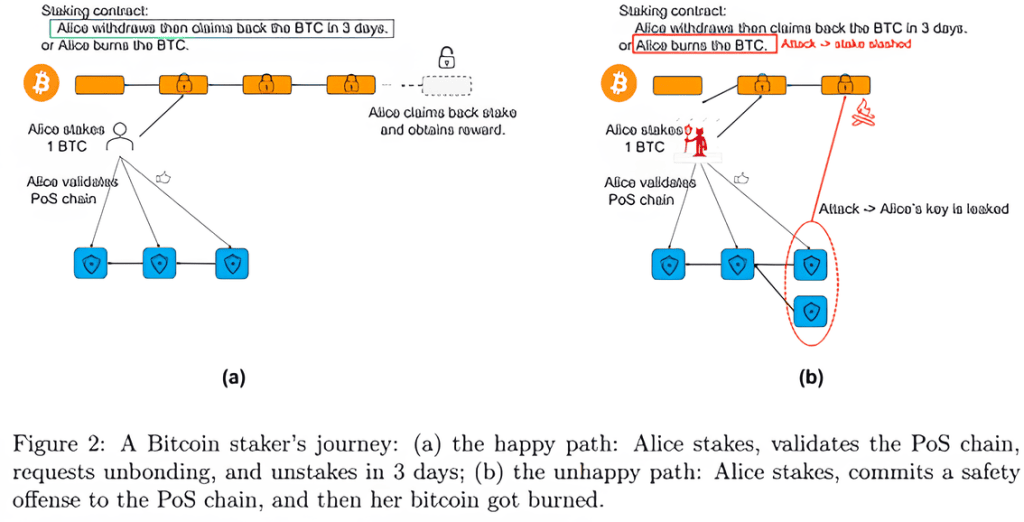

This article describes the structure of “Babylon,” a pioneering Bitcoin (BTC) staking project and considered the largest of its kind today, and the related issues under Japanese law.

Until now, staking has mainly taken place on Proof of Stake (PoS) chains such as Ethereum. Staking in PoS is a mechanism to increase the security of the chain by participating in the validation of transactions on the network, etc., in exchange for a reward.

In contrast, because Bitcoin employs Proof of Work (PoW), it has been believed that, in principle, there is no revenue opportunity from staking in the traditional sense of the term. The most common means of monetization using BTC has been through centralized lending services and tokenization solutions such as wBTC (Wrapped BTC).

Babylon is a project that aims to overcome these limitations of BTC utilization and realize trustless staking using BTC, and is currently one of the most popular protocols in this field. This paper examines its technical structure and issues under Japanese law.

In order to fully understand Bitcoin staking, it is helpful to have a foundational understanding of the staking mechanisms used in PoS chains, as well as the concepts of liquid staking (e.g., by LIDO) and restaking (e.g., by EigenLayer).

For more information on these topics, please refer to the following articles authored by our firm:

| (References) Our previous Article on POS chain staking (in English) ・https://innovationlaw.jp/en/staking-restaking-under-japanese-law/ Our previous Articles on POS chain staking (in Japanese) ・Organizing Legal Issues on Staking 2020.3.17 ・DeFi and the Law – LIDO and Liquid Staking Mechanisms and Japanese Law 2023.10.17 ・EigenLayer and other Restaking Mechanisms and Japanese Law 2024.5.10 |

I. Overview of Legal Issues

| (1) The Babylon mechanism itself does not appear to fall under the custody regulations under the Payment Services Act (PSA). (2) The structure of Babylon is not considered to constitute a collective investment scheme (fund) under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). (3) If a liquid staking provider holds custody of a user’s BTC private key, such a provider may fall within the scope of custody regulations under the PSA. Legal classification should be assessed on a case-by-case basis depending on the structure. (4) Japanese crypto asset exchanges are generally permitted to offer BTC staking services through Babylon under the current legal framework. (5) One practical issue for Japanese crypto asset exchanges is that the rewards granted through the Babylon protocol may be altcoins that are not classified as “handled crypto assets” for that exchange. In such cases, the exchange is not permitted to custody these altcoins on behalf of users under current Japanese regulations. Accordingly, alternative measures must be considered, such as (i) transferring the altcoins to the user’s unhosted wallet, or (ii) selling or swapping them via a DEX or an overseas partner, and then crediting the user with BTC or Japanese yen. |

II. Basic Overview of Babylon

1 What is Babylon’s Bitcoin Staking?

Bitcoin uses PoW (Proof of Work), which means that staking is not possible in the same way as with Ethereum.

Babylon introduces a new mechanism that enables BTC staking, with the following key features:

| 1 BTC is staked not to secure the Bitcoin network itself, but to secure other networks that rely on PoS-like economic security mechanisms, collectively referred to as Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs). 2 Rewards are determined by the secured networks, typically in the form of their native tokens. 3 BTC can be used to secure multiple such networks simultaneously, potentially increasing yield (albeit with higher associated risks). 4 Staking does not require transferring the BTC private key; instead, it is conducted in a trustless and non-custodial manner using one-time signatures (EOTS: Extractable One-Time Signatures). |

2 What does it mean to stake BTC to secure other PoS networks?

One of Babylon’s most important features is that it uses Bitcoin to enhance the security of “other” PoS networks.

The eligible networks are those that meet certain technical requirements and generally fall under the broad category of PoS-based systems—i.e., networks that have their own validator sets.

Currently, Babylon has announced test integrations and partnerships with various types of networks, including rollups, data availability (DA) chains, and oracle networks.

3 PoS Network Security and Staking

n a Proof-of-Stake network, security is provided by validators who stake assets—either their own or those delegated to them by third parties—to verify transactions and produce blocks.

If validators behave dishonestly, the staked assets may be slashed (i.e., partially confiscated), creating a strong financial incentive to act honestly and support the stability of the network.

In many PoS networks, delegated staking is possible, allowing token holders who do not run validators themselves to delegate their tokens to trusted validators.

In such cases, validators are responsible for the staked assets regardless of whether they are self-staked or delegated.

However, in order to participate in staking—either directly or via delegation—users must first acquire the native token of the target PoS network.

For emerging or smaller-scale networks, this presents several challenges:

- There are relatively few holders of the token (due to acquisition costs and price volatility),

- Token ownership may be highly concentrated,

- As a result, there may be a limited number of validators or insufficient total stake, weakening the network’s security guarantees.

Babylon aims to address these challenges by allowing Bitcoin holders to contribute to the security of such networks—collectively referred to as Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs)—without requiring them to acquire the native token or transfer custody of their BTC.

Security participation is instead enabled through a trustless, signature-based mechanism.

4 Enhanced security with BTC

As mentioned above, Babylon introduces a mechanism to enhance the security of PoS-based networks by leveraging BTC, an external asset, to address the inherent security limitations these networks may face.

Specifically, BTC holders contribute economic security by staking their BTC, which is used to support the security of external networks.

Importantly, this BTC collateral is not transferred directly to the PoS networks. Instead, it remains in the user’s self-managed script on the Bitcoin network, and staking is performed via the Babylon protocol through a cryptographic signature (digital proof of intent).

This design enables non-custodial and trustless participation, eliminating the need to deposit or lock up BTC with a third party.

By introducing such externally sourced security, PoS networks can leverage BTC’s high liquidity and market capitalization to reinforce their security infrastructure—without relying solely on their native tokens.

This mechanism is particularly promising for emerging PoS networks, where token distribution may be highly concentrated and the validator set small, leading to weaker security. Babylon’s BTC-based model may serve as a viable complement to address these vulnerabilities.

5 Rewards Are Paid in Tokens on the PoS Network

The rewards for staking BTC through Babylon are not paid in BTC itself, but in the native tokens designated by the PoS network that receives the security service.

From the perspective of the PoS network, this structure allows it to externally source economic security (in the form of BTC) by using its own native tokens as incentives. Through appropriate token issuance and incentive design, the network can attract BTC stakers without requiring external capital.

For BTC stakers, this provides the benefit of earning yield in the form of external PoS network tokens—without needing to transfer or wrap their BTC. This feature may present a new yield opportunity, particularly for long-term BTC holders looking to earn passive returns on their assets.

Risk Associated with Rewards Being Paid in Other PoS Tokens

While Babylon offers BTC holders the opportunity to earn yield, there are several risks associated with the fact that rewards are paid in the native tokens of external PoS networks rather than in BTC.

This structure may also present practical and regulatory challenges, especially for users staking through crypto asset exchanges in Japan. As discussed in Section IV-3 below, it could act as a disincentive for such platforms to offer Babylon staking services.

| Risks Associated with Receiving Rewards in Other Tokens • Price Volatility Risk of Reward Tokens The reward tokens received from PoS networks generally have lower market capitalization and liquidity compared to BTC, making them more susceptible to price volatility. Even if the nominal reward amount is high, a sharp decline in the token price could result in a significantly reduced effective yield. • Liquidity and Redemption Risk If the reward tokens are issued by a relatively niche or illiquid chain, they may be difficult to redeem on the open market, or suffer from large bid-ask spreads, reducing the actual profitability of staking. • Continuity and Stability of Reward Design If the PoS network changes its reward policy or reduces incentives in the future, the economic appeal of Bitcoin staking may diminish. Moreover, if the chain’s operations are unstable, there is a risk that rewards may not be distributed properly or consistently. |

6 Trustless Staking Without Private Key Transfer in Babylon

Babylon is designed to allow BTC holders to participate in network security as providers of economic collateral—autonomously and non-custodially, without transferring their private keys to any third party.

This architecture enables truly trustless staking, eliminating the need for traditional asset transfers or reliance on custodians.

(1) What It Means Not to Transfer the Private Key

In conventional staking and DeFi use cases, utilizing crypto assets typically requires one of the following actions:

- Wrapping the original asset (e.g., BTC) into a token that can be used on another chain (e.g., wBTC)

- Locking the asset into a third-party custodian or smart contract as collateral

Both methods effectively require giving up control of the private key, at least temporarily, which introduces risks such as asset leakage or loss due to smart contract vulnerabilities.

Babylon avoids these risks by enabling signature-based staking mechanism. This allows BTC holders to retain full control over their assets while still participating in economic security provision.

(2) Technical Mechanism: Declaration of Staking Intent via One-Time Signature (EOTS)

Babylon utilizes a cryptographic technique known as Extractable One-Time Signatures (EOTS) to allow BTC stakers to both prove their ownership of BTC and explicitly accept responsibility for contributing to the security of a PoS-based system.

The basic flow of this mechanism is as follows:

| 1.The BTC staker selects a finality provider and generates the transaction data necessary to initiate staking. 2.The transaction includes the following conditional clauses: (i) The designated BTC cannot be transferred for a fixed period (e.g., three days); (ii) If certain predefined conditions arise during that period, the BTC will be sent to a predetermined address (typically a burn address); (iii) However, the BTC staker retains the right to cancel (revoke) the transaction at any time before the fixed period ends, as long as no slashing condition has been triggered. 3.The “predefined conditions” referred to in (ii) generally correspond to slashing events—e.g., if the selected finality provider engages in dishonest behavior (such as submitting double signatures), the BTC will be forcibly sent to the burn address as a penalty. 4.The BTC staker finalizes the process by signing the transaction using a one-time EOTS (Extractable One-Time Signature), thereby proving BTC ownership and formally declaring their intent to participate in security provision. |

This design enables PoS networks to receive a security guarantee backed by BTC, a highly liquid external asset, while the Babylon protocol itself provides a comprehensive framework for detecting malicious behavior and executing slashing penalties.

https://docs.babylonlabs.io/papers/btc_staking_litepaper%28EN%29.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com)

7 Significance and Limitations of Trustless Design

The BTC staking mechanism enabled by Babylon is characterized by a trustless and non-custodial architecture, in the following respects:

- BTC remains in the user’s self-managed script and is never transferred to a third party.

- The intention to provide collateral can be expressed solely through a cryptographic signature (digital proof), without relying on centralized intermediaries or smart contracts.

- Participation in security provision and the receipt of rewards are possible based solely on that signature.

This structure, which minimizes the need for trust in third parties, is closely aligned with Bitcoin’s foundational principles of self-custody and decentralization.

However, it is important to note that the system is not entirely “trustless.”

Certain functions—such as verifying signatures, executing slashing, and distributing rewards—are handled by the Babylon Genesis Chain, described below.

In other words, while BTC itself is never directly deposited or locked up, a degree of “protocol trust” is still required—specifically, trust in the legitimate operation and correct implementation of the Babylon protocol, including the Babylon Genesis Chain.

III. Important Entities in the Babylon Ecosystem

The entities involved in the Babylon ecosystem are diverse, but some of the key participants include following:

1 Important Entities about Babylon

Figure: Babylon Overview

(1) Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs)

• Summary:

Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs) refer to a category of networks (or chains) that enhance their security by integrating Bitcoin’s economic security via Babylon. These networks typically operate on PoS or PoS-like systems and utilize BTC as external collateral to strengthen their security infrastructure.

• Role:

PoS networks, particularly in their early stages, often face security challenges due to a small or overly centralized validator set and insufficient economic collateral. By incorporating BTC through Babylon, BSNs can achieve the following:

- Enhanced Security with BTC

By leveraging BTC—a highly liquid and trusted external asset—PoS networks can strengthen their resilience against network attacks (currently focused on mitigating double-signing risks). - Improved Finality Guarantees

BSNs can obtain “external finality” for their blocks through cryptographic signatures submitted by Babylon’s finality providers, further strengthening consensus assurance. - Incentive Design to Attract BTC Stakers

By offering rewards in their native tokens or stablecoins, BSNs can economically incentivize BTC stakers to participate in securing the network, offsetting the cost of enhanced security.

• Typical Use Cases (Examples):

- Emerging app chains built with the Cosmos SDK

- PoS networks with volatile or weak native token economics

- Ethereum Layer 2 chains

- Gaming chains, DePIN networks, AI chains, and other specialized blockchain applications

- In theory, Babylon can provide security to all PoS networks.

(2) Finality Providers

• Summary:

Entities that observe and verify block finality on PoS networks secured by Babylon, and submit cryptographic finality signatures accordingly.

• Role:

- Generate and submit finality signatures to the Babylon protocol

- Ensure honest behavior, as fraudulent signatures may trigger slashing penalties

• Note:

Finality providers differ from traditional validators in other chains. Their core responsibility is to observe the finality of blocks on the target PoS network and report that information to the Babylon chain.

However, they play a somewhat validator-like role in that they create and submit cryptographic signatures, earn rewards for doing so, and are subject to slashing in case of misconduct.

Comparison of Finality Providers and General PoS Validators

| Item | Finality Provider (Babylon) | General PoS Chain Validator |

| Block Generation | ❌ Not performed | ✅ Performed |

| Finality Observation | ✅ Performed | ❌ Typically not involved (finality is emergent) |

| Signature Type | ✅ Signs finality data | ✅ Signs blocks and voting messages |

| Slashing Risk | ✅ Yes (for fraudulent finality signatures) | ✅ Yes (for double signing, downtime, etc.) |

| Reward Mechanism | ✅ Yes (based on submitted signatures) | ✅ Yes (based on block production and delegation) |

(3) Bitcoin Stakers

• Role:

Hold BTC and contribute to the security of PoS networks by submitting off-chain cryptographic signatures to Babylon.

• Reward:

Receive staking rewards from the PoS networks in return for providing BTC as collateral via Babylon.

• Key Characteristics:

- BTC stakers do not need to transfer their BTC or private keys to any third party.

- They retain full control over their assets while participating in staking.

- The process is non-custodial and trustless by design.

BTC stakers can also delegate their staking to finality providers.

Even in such cases, no BTC or private key is transferred, and the delegation is completed through a non-custodial mechanism.

(4) Babylon Genesis Chain (one of the BSNs)

- The Babylon Genesis Chain is a Cosmos SDK-based PoS Layer 1 blockchain designed to operate the Babylon protocol.

- Although it is one of the Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs), it plays a central role within the Babylon ecosystem, serving as its foundational coordination layer.

| Function | Description |

| Signature Verification | Receives and verifies signatures from BTC stakers and finality providers. |

| Slashing Enforcement | Executes slashing penalties when fraudulent or malicious signatures are detected. |

| Finality Recording | Records the finality of blocks from PoS networks on Bitcoin (e.g., via timestamping). |

| Cross-Chain Relay | Relays verified security information and signatures to other BSNs. |

- If you participate as a finality provider securing the Babylon Genesis Chain, you will receive the chain’s native token, “BABY,” as a reward.

(5) Liquid Staking Protocol (not shown in the figure above)

A protocol that facilitates BTC staking via Babylon on behalf of BTC holders, aiming to improve operational efficiency, usability, and liquidity. While the main focus is on liquid staking, a hybrid model that combines restaking (reuse of the same BTC for multiple networks) may also be adopted where appropriate.

| Key functions: (i)Streamlining Operations Since it is burdensome for BTC holders to individually generate signatures and monitor activity across multiple PoS networks, the protocol handles the following tasks: ・Selection of PoS networks for staking ・Automatic generation and management of EOTS signatures ・Collection and distribution of staking rewards (ii) Issuance and Utilization of Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) The protocol issues liquid staking tokens (e.g., stBTC) backed by the user’s staked BTC position. This allows the user to retain liquidity of their assets even while staking, enabling secondary use in DeFi and other ecosystems. (iii) Complementary Use of Restaking By carefully managing risk, the protocol may reuse the same BTC signature across multiple PoS networks (i.e., multi-staking), thereby maximizing yield. |

2 Supplement: Relationship Between the Babylon Ecosystem and the Babylon Genesis Chain

The relationship between the Babylon ecosystem and the Babylon Genesis Chain is nuanced and may require clarification.

The Babylon Genesis Chain is a PoS Layer 1 blockchain that plays a central role within the Babylon ecosystem. However, it is not synonymous with the ecosystem itself.

The Babylon protocol refers to a broader framework encompassing multiple Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs) that utilize Bitcoin-based economic security via Babylon.

If a participant joins Babylon as a finality provider and provides finality to the Babylon Genesis Chain, they receive “BABY”, the native token, as a reward.

Finality providers currently serve the Babylon Genesis Chain, where they contribute to finality and receive BABY, the native token, as compensation. Although the Babylon protocol is designed to be extendable to other Bitcoin-Secured Networks (BSNs), finality provisioning beyond the Genesis Chain has not yet been implemented. In the future, other BSNs may adopt the Babylon finality mechanism and offer their own tokens as rewards to finality providers.

In addition, the Babylon Genesis Chain has its own set of validators, who stake BABY and participate in block production and consensus. These validators are also rewarded in BABY for their contributions to the network’s operation.

1 Overview of BABY Token: Acquisition Methods and Utility

| Item | Details |

| Token Name | BABY (Native token of the Babylon Genesis Chain) |

| Means of Acquisition 1 | Stake BABY and participate as a validator in block production and validation on the Babylon Genesis Chain |

| Means of Acquisition 2 | Provide finality to the Babylon Genesis Chain using BTC as a finality provider |

| Primary Use Case 1 | Staking collateral for validator participation |

| Primary Use Case 2 | Governance (proposal creation and voting rights) |

| Primary Use Case 3 | Network fees (planned in the future) |

| Additional Notes | Rewards in other BSNs are typically paid in each BSN’s own native token, not BABY |

2 Comparison: Finality Providers vs. Validators (on the Babylon Genesis Chain)

| Item | Finality Provider | Validator (Babylon Genesis Chain) |

| Staked Asset | BTC (non-custodial) | BABY token (non-custodial) |

| Primary Role | Provide finality (submit signatures) to BSNs | Block production and validation on Babylon Genesis Chain |

| Target Chain(s) | Babylon Genesis Chain and other BSNs | Only the Babylon Genesis Chain |

| Reward Token | BABY or BSN-native token (depending on the chain) | BABY token |

| Slashing Risk | Signature invalidation and BTC burn (e.g., double signing) | Slashing of staked BABY (e.g., double signing or downtime) |

| Staking Method | Declaration of intent via BTC signature (held in a self-managed script; delegation also possible) | On-chain BABY token staking (self-custodied; delegation also possible) |

IV. Bitcoin Staking and Japanese Law

Based on the above assumptions, this section outlines the key legal issues related to providing or using a Bitcoin staking service such as Babylon.

In particular, the analysis focuses on two core questions:

- Whether the custody regulations under the Payment Services Act (資金決済法) apply, and

- Whether the fund regulations under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA, 金融商品取引法) are triggered.

1 Babylon and the Custody Regulation of Crypto Assets

In the context of BTC staking via Babylon, a key legal issue is whether the provision of BTC as economic security constitutes the “management” or “custody” of crypto assets under Japanese law.

Under custody regulations based on the Payment Services Act, the primary legal criterion is generally understood to be whether the service provider holds the private key required to transfer the user’s crypto assets.

This interpretation is supported by an official public comment issued in connection with the 2019 amendments to the Act:

“If a business operator does not possess any of the private keys necessary to transfer the cryptographic assets of a user, the business operator is not considered to be in a position to proactively transfer the cryptographic assets of the user, and therefore, basically, is not considered to fall under the category of ‘managing cryptographic assets for others’ as stipulated in Article 2, Paragraph 7, Item 4 of the Payment Services Act.”

In this regard, the private key required to transfer BTC is never shared with or transferred to any entity, including the Babylon Genesis Chain or finality providers.

The technical structure of the system is as follows:

- The BTC staker selects a finality provider and generates the necessary transaction data to initiate staking.

- The transaction includes a conditional instruction, such as:

(i) the BTC will be locked for a specified period; and

(ii) if a slashing event occurs, the BTC will be transferred to a predefined burn address. - The BTC staker signs this transaction using a one-time EOTS (Extractable One-Time Signature), thereby proving ownership and expressing intent to participate in staking.

This design enables BTC to serve as economic security without transferring control of the private key, ensuring that the BTC remains in the staker’s custody unless slashing conditions are triggered.

Accordingly, Babylon and finality providers would generally not be considered to fall under custody regulations under the Payment Services Act.

However, it should be noted that certain Liquid Staking Protocols may offer services that involve taking custody of users’ private keys. In such cases, those entities may indeed be subject to custody regulations, and a case-by-case legal assessment would be required.

2 Babylon and the FIEA Regulations

In Babylon, BTC is provided as economic security, and BTC stakers receive compensation while bearing certain risks such as slashing. From this structure, a legal question arises as to whether Babylon might be classified as a “fund” (collective investment scheme) under Japanese law.

(1) Definition of “Fund (Collective Investment Scheme)” under Japanese Law

Article 2, Paragraph 2, Items 5 and 6 of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (“FIEA”) broadly define a “fund” (collective investment scheme) as follows:

| (A)Covered Forms of Rights (any of the following): 1. Partnership agreement 2. Silent partnership agreement 3. Investment limited partnership agreement 4. Limited liability partnership agreement 5. Membership rights in a general incorporated association 6. Other similar rights (excluding those established under foreign laws) Note: Items 1–5 are illustrative; “other rights” are interpreted broadly, regardless of legal form. (B)Description of the Scheme (all of the following must be satisfied): ・Investors contribute cash or assets (including crypto assets, per Cabinet Order); ・The contributions are used in a business; and ・Investors have rights to receive dividends or a share in the property derived from that business. (C)Exclusions: The scheme does not apply where all investors are actively and substantially involved in the business (per Cabinet Order requirements); or Where investors are entitled to returns only up to the amount they invested (limited liability form). (D)Foreign Funds: Similar rights based on foreign laws may also be regulated under separate provisions. |

(2) Applicability of Fund Regulations to the Babylon Protocol

While Babylon might fall within the category of “other similar rights” in (A) above and does not appear to meet the exclusions under (C), it is unlikely to satisfy all of the conditions under (B). Accordingly, it may not constitute a fund under the FIEA, for the following reasons:

- The BTC provided by the staker is positioned as economic collateral, not as a capital contribution or investment to Babylon’s operating entity.

- The staking rewards are not dividends from Babylon’s business, but rather token-based rewards issued by the PoS networks that benefit from the staker’s security provision.

- The BTC staker does not entrust assets to any centralized management entity but simply interacts with the protocol by signing a transaction; the assets remain in self-custody unless slashed.

From these perspectives, Babylon’s BTC staking mechanism does not appear to meet the definition of a fund under the FIEA.

(3) Applicability of Fund Regulations to Finality Providers and Liquid Staking Protocols

Babylon allows BTC stakers to delegate their staking authority to finality providers. However, since this process does not involve the transfer of private keys, such delegation is not likely to fall under a fund regulation.

On the other hand, certain Liquid Staking Protocols may offer services that involve taking custody of users’ private keys. In such cases, a careful legal analysis is required to determine whether such schemes meet the definition of a fund under the FIEA, particularly in light of the structure of asset control and contribution.

V. Crypto Asset Exchanges and Babylon Staking

This section examines the legal and operational issues that may arise when a Japanese crypto asset exchange operator performs BTC staking via the Babylon protocol using assets deposited by users.

1 Position of Staking within Crypto Asset Exchange Business

Many crypto asset exchanges in Japan provide staking services as part of their business operations.

To our understanding, as long as users do not bear the risk of slashing (i.e., potential loss)12, such services are generally treated as part of the core business of “receiving deposits of crypto assets” as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 15, Item 4 of the Payment Services Act.

This legal interpretation should remain applicable even when Babylon is used as the underlying protocol—no special legal treatment or additional licensing is expected to be required.

2 Compatibility with Cold Wallet Regulations

Under Article 60-11, Paragraph 2 of the Payment Services Act and Article 27, Paragraph 3, Item 1 of the Cabinet Office Ordinance on Crypto Asset Exchange Services, crypto asset exchanges in Japan are required to segregate users’ crypto assets from their own assets and hold them in cold wallets.

In most PoS staking systems, private keys used for asset transfers do not need to be moved; rather, a separate validator key is used. This practice is generally considered not to conflict with cold wallet requirements.

In Babylon, there is no concept of a validator key. Instead, staking is performed via cryptographic signatures called Extractable One-Time Signatures (EOTS). Importantly, the private key for BTC remains in the possession of the BTC staker—in this case, the exchange operator—and is never transferred or exposed to third parties.

Therefore, since the exchange does not move or manage private keys externally, Babylon staking is not expected to conflict with cold wallet custody obligations.

3 Handling of Altcoin Rewards in Babylon

A unique practical issue with Babylon staking is that while BTC is used as the staked asset, the rewards are typically paid in the native tokens (i.e., altcoins) of the target PoS network, rather than in BTC itself.

For example, when staking ETH, both the staked asset and the reward are ETH, which poses no legal or operational issues for exchanges that have already registered ETH as a “handled crypto asset” with the Financial Services Agency (FSA).

In contrast, when staking BTC via Babylon, the resulting rewards may be in the form of tokens such as BABY or other native tokens of PoS networks that are not registered as handled crypto assets. This presents a compliance challenge under the Payment Services Act.

Several operational approaches can be considered:

(1) Custody of Altcoins by the Exchange and Grant to Users

In this approach, the exchange holds the altcoins it receives as rewards and allocates them to users.

While it may be possible to register certain major tokens (e.g., BABY) as handled crypto assets, and some tokens associated with Babylon partner networks (e.g., ATOM, SUI) are already listed in Japan, it is not realistic to file individual registrations for every potential reward token.

(2) Direct Delivery of Altcoins to Users’ Self-Managed Wallets

Here, the exchange does not custody the reward tokens but transfers them directly to each user’s self-managed wallet. This bypasses the need to register the tokens as handled crypto assets.

However, this approach presents practical challenges: requiring users to manage wallets for a wide range of altcoins is burdensome from both a UX and operational support perspective. It also introduces potential transaction costs and operational risks.

(3) Sale or Exchange of Altcoins, and Payment of Rewards in BTC or JPY

Under this method, the exchange converts the reward altcoins into BTC or JPY (e.g., via a DEX or an overseas partner), and then distributes those converted assets to users as rewards.

While this may raise concerns that the exchange is engaging in crypto asset exchange services involving unregistered crypto assets, such risks may be mitigated through appropriate contractual arrangements.

Specifically, if the agreement with the user clearly states that:

- The user deposits BTC for staking, and

- The exchange will return rewards in BTC or JPY (not altcoins),

then the exchange’s sale or swap of the altcoins can be viewed as part of its internal process for sourcing rewards, rather than as a crypto asset exchange activity involving third parties.

In this structure, the exchange merely acquires and disposes of unregistered tokens on its own account, which is generally not considered a regulated activity under current law.

(4) Conclusion

In light of the above, under the current regulatory framework, it appears that the most realistic and effective approach for crypto asset exchanges is to structure their operations based on scheme (3).

That said, from the perspective of BSNs, there are concerns about potential ongoing selling pressure caused by continuous liquidation of reward tokens. Therefore, the sustainability of the system as a whole should also be carefully considered in future discussions.

Acknowledgments

In preparing this article, I received valuable input from the teams at Kudasai Inc. and Next Finance Tech Inc., both of whom are well-versed in Babylon staking. I also benefited from informal yet insightful suggestions from individuals involved with the Babylon protocol.

However, any remaining errors or interpretations are entirely my own and do not represent the official views of any specific entity

Disclaimer

The content of this document has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority and represents a general legal analysis based on interpretations currently considered reasonable under applicable Japanese law. The views expressed herein reflect the current thinking of our firm and are subject to change without notice.

This document does not constitute an endorsement of any specific staking mechanism, including Bitcoin staking, the Babylon protocol, liquid staking services, or any related technologies or platforms.

This material is provided solely for informational and blog purposes. It does not constitute legal advice, nor is it intended to be a substitute for legal counsel. For advice tailored to your specific circumstances, please consult with a qualified attorney.

1.Introduction

As seen in Ethereum network, staking—the process of locking a certain amount of crypto assets on a blockchain for a set period to contribute to transaction validation (Proof of Stake), earning rewards in return—is gaining traction globally as well as in Japan. Major Japanese crypto asset exchanges now offer staking services, contributing to its expansion. This paper outlines key legal issues related to staking under Japanese law and briefly addresses the concept of restaking, which is a mechanism in which existing staked crypto assets or staking rewards are staked again to earn additional rewards, with the aim of enhancing network security and enabling new services.

2.Legal Issues Related to Staking Under Japanese Law

Regulatory applicability depends on the manner in which staking is conducted and its legal framework. Relevant regulations include those governing Crypto Asset Exchanges and Funds as referenced and further explained below.Staking one’s own crypto assets remains unregulated under such regulations, therefore, this discussion focuses on cases where a service provider stakes on behalf of users. To summarize the key conclusions in advance:

| Staking Structure and Legal Framework | Applicability of Crypto Asset Exchange Regulations / Fund Regulations as per Japanese Law |

| Service provider does not receive the user’s private key (only delegation) | No applicable regulations |

|

Service provider gets the user’s private key |

|

| Legal structure: “Custody” | Crypto Asset Exchange regulations apply (registration as a Crypto Asset Exchange) |

| Legal structure: “Investment” | Fund regulations apply (registration as a Type II Financial Instruments Business Operator) |

| Legal structure: “Lending” | No applicable regulations |

Custody, Investment, and Lending are key legal classifications in the regulatory framework for staking services. While details will be discussed later, these terms can be briefly defined as follows:

✓Custody refers to the management of crypto assets on behalf of users. Possession of private keys is a key factor in determining regulatory applicability of Custody. If structured as Custody, it falls under Crypto Asset Exchange regulations under the Payment Services Act (PSA).

✓Investment refers to a scheme where users contribute funds (including crypto assets) to a service provider, which then utilizes them for business operations (e.g., staking) and distributes profits to the users. If structured as Investment, it falls under Fund regulations governed by the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA).

✓Lending refers to an arrangement where users lend their crypto assets to a service provider, which manages the crypto assets at its discretion and returns them after a specified period. If recognized as a Lending agreement, it is generally not subject to PSA or FIEA regulations.

3.A Short Introduction to Crypto Asset Exchange Regulations and Financial Regulations

Under Japanese law, Crypto Asset Exchange regulations under the PSA, Article 2, Paragraph 15, apply to the following activities:

- Buying, selling, or exchanging crypto assets.

- Intermediating, brokering, or acting as an agent for these activities.

- Managing users’ funds related to 1 and 2.

- Managing crypto assets on behalf of others.

Among these, staking is particularly relevant to Item 4., which refers to the Custody services.

Regarding “managing crypto assets on behalf of others” (hereinafter referred to as “Custody”), the Financial Services Agency (FSA) guideline3 states:

“[…] in a case where the business operator is in a state in which the business operator is able to proactively transfer a Crypto-Asset of a user, such as a case where the business operator holds a secret key [Author’s Note: referring to a private key] sufficient to enable the business operator to transfer the Crypto-Asset of the user without any involvement of the user, either alone or in cooperation of an affiliated business operator, such a case falls under the management of Crypto-Assets.”

This indicates that possession of private keys is a key factor in determining regulatory applicability of Custody.

Additionally, staking may also be subject to Fund regulations governed by FIEA (Article 2, Paragraph 2, Item 5). This FIEA applies where users contribute funds (including crypto assets) to a service provider, which then utilizes them for business operations and distributes profits to the users.

(a) Case where the service provider does not hold the user’s private key

If a service provider only receives delegation from users without holding their private keys4, it does not qualify as a Custody activity under the FSA guideline as quoted above and is not subject to Crypto Asset Exchange regulations under the PSA.Additionally, in this case, since users do not contribute funds to the service provider —given that the service provider cannot transfer the crypto assets for business operations without possessing the private key— it does not constitute an “Investment” and therefore, Fund regulations under the FIEA do not apply either.

(b) Case where the service provider holds the user’s private key

If a service provider holds the user’s private key, it may be classified as a Custody activity under the PSA. Additionally, depending on the legal structure of the arrangement, the user’s contribution could be considered an “Investment,” making it subject to Fund regulations under the FIEA.

First, if the arrangement is structured as a “Custody,” the provider is deemed to be managing the user’s crypto assets on their behalf. This qualifies as a Custody activity under Crypto Asset Exchange regulations and falls under the Payment Services Act (Article 2, Paragraph 15, Item 4).

If the legal structure is such that the provider receives “Investment” of crypto assets from users, it does not meet the Custody regulation requirement of “managing crypto assets on behalf of others,” as the assets are received for business use rather than for custodial management on behalf of users. Therefore, Custody regulations under the PSA do not apply. However, since the provider uses the contributed funds to operate a business (staking) and distributes the revenue to users, it is likely subject to Fund regulations under FIEA.

If the arrangement is structured as Lending, where the user lends crypto assets to the service provider, which manages them at its discretion and returns them after a specified period, rather than making a Custody (where assets are held and managed on behalf of the user) or an Investment (where assets are contributed with an expectation of return), no specific regulations apply. However, according to the aforementioned FSA guideline5, “The borrowing of Crypto-Assets […] falls under the management of Crypto-Assets […] if a business operator substantially manages a Crypto-Asset on behalf of another person under the name of the borrowing of a Crypto-Asset such that the user can receive the return of the Crypto-Asset borrowed at any time at the request of the user. “

Therefore, regulatory authorities may classify such circumvention schemes as a Custody activity, making them subject to Custody regulations under the PSA.

Thus, even when a service provider holds the user’s private key and conducts staking, the applicable regulations vary depending on the legal structure of the arrangement. However, in practical business operations, the distinction between “Custody”, “Investment” and “Lending” is not always clear. To determine the applicable regulations, it is useful to analyze the staking scheme based on the following factors:

- Whether the rewards are received by the service provider and then distributed to the user, or are they directly distributed to the user.

- If the service provider receives the rewards first and then distributes them to the user, and whether the distribution is fixed or linked to revenue.

- Whether the slashing risk, which refers to the risk of staked assets being partially or fully slashed if a validator violates network rules or engages in misconduct, is borne by the service provider or the user.

Based on these factors, the conclusions for typical cases are summarized as follows. However, if a case does not fit within these typical scenarios, determining whether it qualifies as Custody service or a Fund Investment can be challenging.

- If the amount of rewards paid by the service provider to the user is predetermined and the user does not bear the slashing risk: Custody regulations (i.e. PSA) apply.

- If the amount of rewards paid by the service provider to the user is linked to the staking rewards earned by the service provider, and the user bears part of the slashing risk (i.e., there is no principal guarantee): Fund regulations (i.e. FIEA) apply.

- If the arrangement is structured as a crypto assets Lending agreement, and in substance, it is recognized as a Lending rather than a demand payment or similar arrangement (i.e., one where users can request repayment at any time, meaning the service provider cannot manage the crypto assets at its discretion for a specified period, thereby lacking a key element of Lending): Neither PSA or FIEA apply.

The licenses required for service providers under each scheme are summarized as follows:

- If classified as a Custody activity, registration as a Crypto Asset Exchange is required.

- If classified as a Fund, registration as a Type II Financial Instruments Business operator is required.

- If classified as Lending, no registration is required. However, if a financial instruments business operator engages in a Lending business, approval for ancillary business under the FIEA is required.

4.Legal Issues Related to Restaking Under Japanese Law

(1) Structure of Restaking

Restaking is a scheme where crypto assets that have already been staked are staked again in another protocol.

The demand for restaking arises from two key factors: enhance security of certain decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols and similar services and enabling users to obtain higher yields.

If a DeFi service uses its own Proof of Stake token for validation of transactions and hence its security, its effectiveness may be limited due to low token value or poor distribution and can be open to security vulnerabilities through holding a significant number of the related tokens. Restaking solves this by reusing staked crypto assets (e.g., ETH) to provide the security of major public blockchains like Ethereum.

In return, DeFi services share rewards with crypto assets holders, who also bear slashing risks. This allows holders to earn additional rewards on top of their staking returns, boosting overall yields.

(2) Legal Issues Related to Staking Under Japanese Law

The key legal issues related to restaking under Japanese law include:

- Whether the holding of users’ crypto assets by a restaking service qualifies as a “Custody” service, potentially making them subject to custody regulations (i.e. PSA).

- Whether the distribution of rewards to users, along with their exposure to slashing risk, could fall under Fund regulations (i.e. FIEA).

Regarding Custody regulations, the applicability of Custody regulations depends on the structure of the restaking service. However, based on the previously mentioned stance of the FSA on Custody, if the crypto assets are managed by a smart contract and the restaking service provider does not have the technical ability to transfer the crypto assets, Custody regulations would not apply.

Regarding Fund regulations, the application of Fund regulations requires that the contributed assets be used to conduct a business. In the case of restaking, if crypto assets are merely locked as a form of collateral to cover potential penalties from slashing, rather than being allocated for business operations, it would not meet the legal definition of an Investment. Therefore, Fund regulations would not apply.

Note that, as with staking, the applicable regulations may vary depending on the specific structure of the restaking scheme.

I. Introduction

Japan has enacted and improved crypto regulations since 2017. Japan was once one of the most crypto-friendly nations in the world, but after 2018, it adopted a stricter regulatory stance. It is, however, now becoming more friendly to the Web3 industry again, with an intention to attract foreign investment.

This article provides an overview of cryptoasset regulations in Japan in 2024.

History of Cryptoasset Regulations in Japan

| Early Friendly Era | |

| February 2014 | MtGox, located in Shibuya, Tokyo, and the largest exchange in the world, went bankrupt. |

| March 2014 | Japanese LDP (Liberal Democratic Party, a governing party in Japan) discussed with the government and decided not to regulate virtual currency at that stage but asked the industry to form a self-regulatory organization. |

| May 2016 | Japan enacted the first virtual currency act in the world. The act was made as an amendment to the Payment Service Act (“PSA”). The act was friendly to startups and intended to foster the industry. |

| April 2017 | The amended PSA stated above was enforced. |

| 2017 | There were ICO booms all over the world, and the price of crypto went up. The trading volume of Japanese exchanges became number 1 in the world. Many foreign players came to Japan to start their business. |

| Era of Stricter Regulation | |

| February 2018 | A massive hacking incident, under which approximately JPY 58 billion equivalent NEM was hacked, happened in Japan (Coincheck incident). |

| 2018-2021 | After the Coincheck incident, the Japanese government tightened the operation of the regulation. Many exchanges received business improvement orders and suspension orders, and the market became shrunk. |

| May 2020 | The amended PSA and the amended FIEA were enforced. |

| Era that Web3 became a national strategy | |

| 2021- | The Japanese government’s national growth strategy in 2021 includes the statement that Web3 became one of the national strategies. Under this strategy, the LDP’s Web3 project team has issued policy recommendations titled the Web3 White Paper5in order to foster Web3 every year since 2022. |

| June 2022 | Japan enacted one of the world’s earliest stablecoin regulations. The act was made as an amendment of the PSA and the Banking Act. |

| 2022 | In 2002, there were collapses of Tera Luna, Three Arrows Capital, and the FTX Group. As a result, the global regulatory environment became stricter. However, Japan had already implemented stringent regulations, which proved effective. (*1) Therefore, Japan did not need to change its regulations even after these collapses.

(*1) Even in the FTX Group’s bankruptcy, the assets of FTX Japan’s customers were all preserved because the regulations required 100% of users’ assets to be segregated. |

| June 2023 | Stablecoin regulation was enforced. |

| May 2024 | DMM Bitcoin was hacked, resulting in a loss of approximately JPY 48.2 billion worth of Bitcoin. However, we have not seen any regulatory tightening in response to this incident at this stage. |

II. Cryptoasset, NFT, and Stablecoin Regulation

1. Definition of Cryptoassets

The PSA defines cryptoassets as property value with the following elements:

| (i) which is recorded by electronic means and can be transferred by using an electronic data processing system, (ii) which can be used in relation to unspecified persons for the purpose of paying consideration for the purchase or leasing of goods, etc. or the receipt of provision of services and can also be purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparties, and (iii) excluding the Japanese currency, foreign currencies, currency-denominated assets, and Electronic Payment Instruments. |

2. Cryptoasset Exchange Services

(1) Definition

Under the PSA, the Cryptoasset Exchange Service means any of the following acts carried out in the course of trade:

| (i) sale and purchase of cryptoassets (i.e., exchange between cryptoassets and fiat currency) or exchange of cryptoassets into other cryptoassets; (ii) intermediary, brokerage, or agency service for the acts described above (i); (iii) management (custody) of fiat currency on behalf of the users/recipients in relation to the acts described above in (i) and (ii) and (iv) management (custody) of cryptoassets on behalf of the users/recipients. |

(2) Meaning of “in the course of trade”

Sales and purchases of cryptoassets to Japanese residents are not subject to the regulation unless they are conducted “in the course of trade (gyo to shite)”. An act in the course of trade is generally understood to be a repetitive and continuous act vis-à-vis the public. For example, trading in cryptoassets for one’s own investment purposes or taking custody of cryptoassets of a wholly owned subsidiary are not considered acts in the course of trade.

It should be noted that just because your clients are only institutional investors is not considered as it is not in the course of trade.

(3) Solicitation to Japanese Residents

Whether or not a CESP solicits Japanese residents is also considered an important factor in determining the regulation’s application. The determination of whether solicitation towards residents of Japan is being conducted is made on a case-by-case basis. For instance, actions such as not blocking access to a website from Japan, providing information in Japanese, or introducing products at events in Japan could be considered factors that indicate solicitation towards residents of Japan.

(4) Management of Cryptoassets

The custodian of cryptoassets shall take the CESP license. According to the FSA guidelines, whether each service constitutes the management of cryptoassets should be determined based on its actual circumstances. Generally, if a service provider can technically transfer its users’ cryptoassets, it falls under the category of the management of cryptoassets. If a service provider does not possess any of the private keys necessary to transfer its users’ cryptoassets, the service provider is basically not considered to manage cryptoassets.

Accordingly, wallet services, such as non-custodial wallets, where the users manage the private key on their own, are not considered to constitute the management of cryptoassets.

(5) Intermediary, Brokerage, or Agency Service

An intermediary generally means a factual act that involves efforts to conclude a legal act between two others. Brokerage or agency service means to perform a legal act in one’s own name and for the account or on behalf of another person.

With respect to a purchase and sale agreement of cryptoassets between third parties, the acts of (i) soliciting the signing of the agreement, (ii)explaining the product for the purpose of solicitation, and (iii) negotiating the terms and conditions fall, in principle, under the category of an intermediary.

The mere distribution of product information papers, etc., may not fall under the category of an intermediary and should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

(6) Requirements for the License and Cost

The PSA requires minimum capital, financial requirements, a physical office, a sufficient number of personnel on staff, segregation of assets, an annual audit, a customer identity verification system, accountability to users, protection of person/s’ information, including sensitive information, and, if outsourced, must retain authority. The service provider must be equipped with the systems for adequate operation and legal compliance deemed necessary to operate a Cryptoasset Exchange Service appropriately and securely. Although the applicant must have a minimum capital base of at least JPY 10 million, and it must not be in negative assets, from our experience, the cost of obtaining the license and starting the internet exchange business can be more than JPY 1 billion.

(7) Exchange M&A

We are often asked by companies interested in entering the Japanese crypto market whether they can start their business by acquiring an already licensed CESP rather than obtaining a new license. The answer is Yes. Regulatory speaking, change of major shareholders is done just ex-post notification and you can start your business after purchasing the already licensed CESP.

The major issue here is that the purchased CESP shall satisfy the governance and compliance levels, which are similar to those a new licensed exchange shall achieve. If one purchases a cheap CESP, which is just having a license but has not done a business actively, to reach these levels might be difficult and time-consuming. Furthermore, if you wish to change the business model or system of the purchased CESP, you must provide an explanation to and obtain approval from the FSA. The cost of purchasing the licensed CESP, combined with this additional expense, can sometimes be comparable to the cost of obtaining a new license. Therefore, careful consideration is necessary.

3. Crypto Exchange’s Obligations

(1) Management of Users’ Property

The PSA requires the users’ cryptoassets to be segregated from the CESP. Further, the CESP shall keep (i) at least 95% of the users’ cryptoassets in cold wallets and (ii) equivalent to 100% minus those kept in the left column of its own cryptoassets in cold wallets. Thus, as a consequence, the CESP shall hold the equivalent of 100% of users’ cryptoassets in cold wallets.

With respect to fiat currency, the CESP shall deposit its users’ fiat currency in a bank account under a different name from where the CESP deposits its own funds.

A CESP must undergo an annual audit of its financial statements and segregation of assets.

(2) Anti Money laundering

Anti Money Laundering law requires CESPs to conduct a know-your-customer of users. Stricter regulations for anti-money laundering came into effect on June 1, 2023. According to the new Travel Rules, when assets over a certain amount are sent by a user, the receiving and sending CESPs must share information about the users. The lack of interoperability in such information-sharing systems has prevented users from sending and receiving cryptoassets between some CESPs.

4. DEX

The regulations applicable to decentralized exchanges (DEX) are not clear. There is an argument that the regulations do not apply to exchanges that are completely decentralized and have no administrator at all, as there is no entity subject to crypto regulations. However, it is necessary to carefully consider whether there is truly no administrator. Further, entities that provide access software to a DEX may be subject to the regulations for being intermediaries.

As stated later in section III. 1, the sale of cryptoassets issued by oneself is subject to crypto regulations. Providing liquidity to a DEX for cryptoassets issued by oneself may also be considered as engaging in the sales of the cryptoassets.

5. NFT

Pure NFTs, such as trading cards and in-game items recorded on blockchains that do not function as payment instruments, are not considered cryptoassets. The FSA states that the distinction between cryptoassets and pure NFTs is as follows:

(i) the issuer of the NFTs prohibits its use as a payment instrument by technical feature or by agreement

(ii) the quantity and price of the NFTs are not suitable as a payment instrument (specifically, one NFT costs more than ¥1,000 or the total number of the NFTs issued is less than 1 million).

Generally speaking, pure NFTs are not regulated in Japan. Please, however, note that whether NFTs are considered as “pure” NFTs needs careful discussion. For example, if an NFT gives some dividend or economic benefit, it might be considered as a security. Further, an NFT, which is linked to real-world assets, might require a discussion of whether regulation of real assets may apply.

6. Stablecoins

Japan was one of the first countries in the world to establish stablecoin regulations. Stablecoins pegged to fiat currency are defined as electronic payment instruments and require a license different from CESP to offer the related service.

Other stablecoins that adjust their value through algorithms could be regulated as cryptoassets or securities. Stablecoins classified as cryptoassets are subject to crypto regulations, while stablecoins classified as securities are subject to securities regulations (FIEA).

III. Crypto Financing

1. ICO, IE

ICO (Initial Coin Offering) is an act of issuing and selling tokens to raise fiat currency or crypto assets from the public. ICO is regulated in Japan. The applicable regulations depend on the legal nature of the issued tokens. If the tokens are considered securities, the token issuance will be regulated by the FIEA. If the tokens are considered cryptoassets, the token issuance will be regulated by the PSA.

The issuance of new cryptoasset-type tokens in Japan is generally done by IEO (Initial Exchange Offering). IEO is an act of raising fiat currency or cryptoassets by an entity entrusting the sales of tokens to a licensed CESP. In the case of IEO, if the issuer itself does not conduct sales activity, the issuer does not need to take the crypto exchange license. If, however, the issuer itself wants to conduct sales activity for its new tokens, it needs to have a crypto exchange license, which requires significant cost and time compared to IEO. Several IEO projects have already been launched in Japan.

The IEO process requires examinations by the exchange, JVCEA, a Japanese self-regulatory organization, and the FSA. The examination checks the feasibility of the project for which the funds will be used, the financial soundness of the issuer, and other factors.

2. SAFT, SAFE

SAFT (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens) is a way to raise funds in exchange for the right to purchase tokens to be issued in the future. SFAT targeting Japanese residents is considered to be subject to fund regulation or crypto regulation, depending on the legal nature of the agreement. However, both regulations do not apply unless the act is done in the course of trade, so we may argue that entering into a SAFT with limited numbers of specific persons, such as business partners who will contribute to developing projects, should not be regulated.

SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) with token warrant is subject to general equity investment regulations, depending on the attributes of involved entities and investors.

Japanese entities sometimes use J-KISS, a Japanese convertible equity, with a side letter that provides tokens.

IV. Crypto Staking

Generally speaking, we believe staking service for POS tokens is not regulated in Japan. For example, staking one’s own cryptoassets or becoming a validator for ETH is not regulated in Japan.

Not all staking services, however, are exempted from the regulation. If service providers manage the private keys of users’ cryptoassets (we understand some exchanges provide those services), custody regulation may apply. In addition to managing private keys, if the service providers distribute rewards as well as slashing penalties to the users, fund regulations might apply.

We understand that there are some NFT projects that say that they sell NFTs for crypto, and purchasers can stake NFTs, and can get rewards. We understand fund regulation might apply to such cases, especially in cases where staking does not have any actual usage for providing security.

V. Crypto Lending

In crypto lending services, a service provider borrows cryptoassets from users for a certain period of time and pays a lending fee in exchange. No regulation applies to that lending because the Money Lending Business Act regulates money lending, but it does not deem cryptoassets as money.6