Starting with Bitcoin in 2009, crypto assets have come a long way. Now, more than ten years later, the ecosystem is more diverse than ever, and bitcoin and other crypto assets are on the verge of becoming a new asset class. At the same time, blockchain technology has made significant progress and evolved from a pure state transition system to fully programmable networks. 2nd and 3rd generation networks allow other projects to build dApps on their platform and to deploy smart contracts to issue their own tokens. With the rise of these platforms, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), Initial Exchange Offerings (IEOs), and Security Token Offerings (STOs) have become a popular mechanism to raise funds. The flexibility offered by 2nd and 3rd generation networks also opened up new possibilities for more complex applications such as DeFi.

The potential of blockchain technology has also been recognized by governments around the globe. Experiencing pressure from projects such as Libra, some of them have intensified their research on central bank digital currencies and other blockchain applications.

While the industry is increasingly professionalized, major hacks exposed vulnerabilities in the existing infrastructure. Money laundering is another concern for policymakers. In view of these challenges and an increasingly diversified environment, the Japanese legislator amended the Japanese crypto regulations and published subsidiary legislation more recently. The changes are entering into force on May 1, 2020.

In this article, we take a closer look at the regulatory treatment of different digital assets, analyze the primary and secondary markets for them and provide an overview of different players in the industry, reaching from exchanges to liquidity providers and custodians.

Our article does not consider the current regulatory environment. For more information on the existing framework, please visit our older articles, which can be found here.

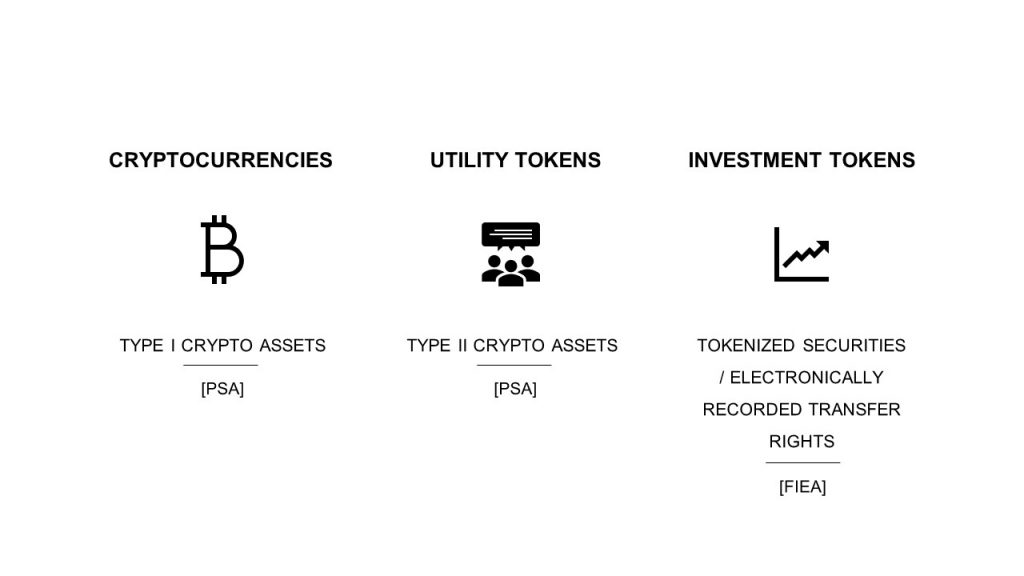

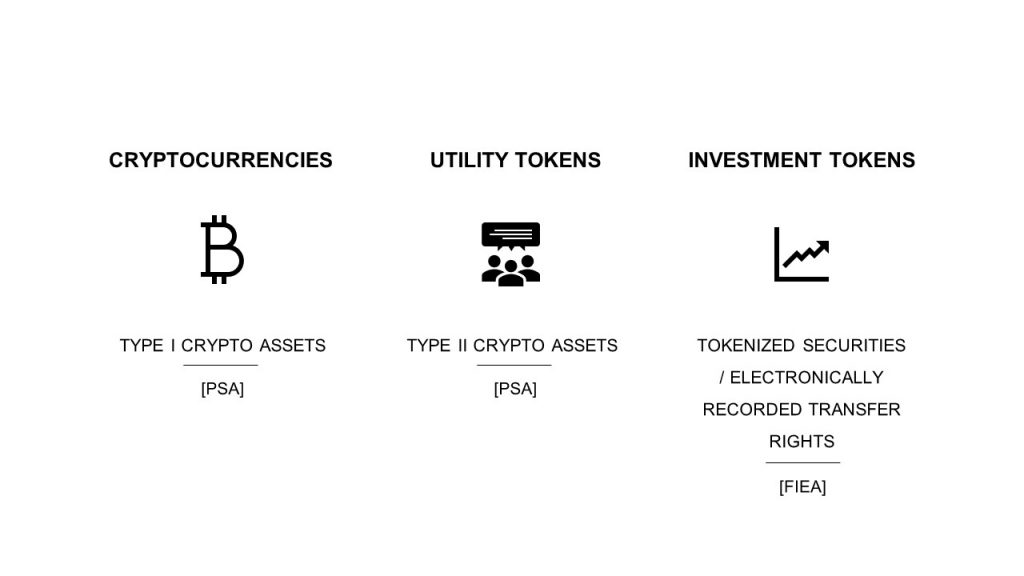

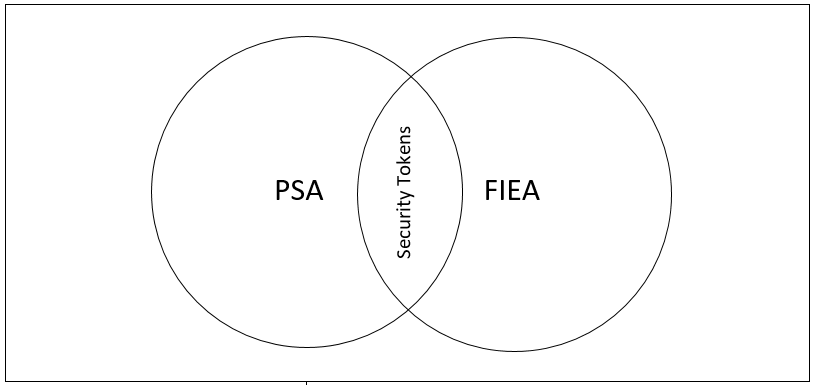

There is no general definition of digital assets under Japanese laws. Rather, the Payment Services Act (PSA) and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) define certain types of digital assets. The definitions are mutually exclusive and – seen as a whole – form a complete picture covering cryptocurrencies, utility tokens and investment tokens.[1] Non-fungible tokens (NFT) and stable coins[2] are not necessarily covered by the definitions in the PSA and the FIEA.

The PSA defines crypto assets exhaustively. Type I crypto assets are defined as property value that can be (i) used with unspecified persons for purchasing goods or services, (ii) purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparty, and (iii) transferred electronically.[3]

Type II crypto assets are property values that can be (i) mutually exchanged with type I crypto assets with unspecified persons acting as a counterparty and (ii) transferred electronically.[4]

Currency denominated assets and electronically recorded transfer rights as defined in the FIEA are explicitly excluded from the definition of crypto assets.[5]

Type I crypto assets: cryptocurrencies

Type II crypto assets: utility tokens

For a better understanding of electronically recorded transfer rights, it is worth looking at the definition of securities under the FIEA. The FIEA contains a comprehensive list of securities and distinguishes between type I and type II securities. Type I securities are traditional securities such as bonds and stocks, which are generally perceived as being highly liquid.[6] Type II securities are, for example, units in a fund, beneficial interests in a trust, membership rights in a general partnership or limited partnership, and equity in limited liability companies.[7] These securities are generally much less liquid than type I securities and are therefore subject to lighter regulation. With the occurrence of tokenization, type II securities became, however – at least in theory – much more liquid. As a response, the legislator introduced electronically recorded transfer rights into the FIEA. These rights represent type II securities which are treated as type I securities.[8]

The FIEA defines electronically recorded transfer rights as (i) electronically recorded property values that (ii) represent type II securities and can be (iii) transferred by electronic means. In addition, (iv) there must not be any liquidity constraints or other circumstances specified by cabinet order.[9] Tokens that are sold to professional investors and for which the transferability is technically restricted, fall under the exemption of item (iv).[10]

Tokens representing type I securities are not covered by the definition of electronically recorded transfer rights and are therefore not excluded from the definition of crypto assets.[11] According to unofficial statements, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) considers type I securities as currency denominated assets, however, which are excluded from the definition of crypto assets as well.

Crypto derivatives such as CFDs, futures, options, and swaps have become increasingly popular more recently. Some of them are said to legitimize crypto assets as a whole and to provide additional liquidity to crypto markets. In Japan, crypto derivatives account for roughly 90 percent of the total crypto trading volume.[12]

Crypto assets as defined in section 1.1 above are financial instruments within the meaning of the FIEA.[13] Derivatives using crypto assets as underlying or crypto asset indices as reference indices are therefore covered by the FIEA.[14] The FIEA distinguishes between derivatives transactions conducted on financial instruments market and OTC derivatives transactions.

Market derivatives transactions include[15]

OTC derivatives transactions include[16]

Excursion – Physical Settlement and Crypto Asset Exchange License

Crypto assets are deemed money under certain provisions of the FIEA.[17] Derivatives transactions may therefore be settled in cash or physically, i.e. by using crypto assets for settlement. The guidelines for crypto asset exchanges explicitly state that a crypto asset exchange license is not required in such cases.[18] In cases of margin trading where crypto assets are taken as collateral, something different might apply.

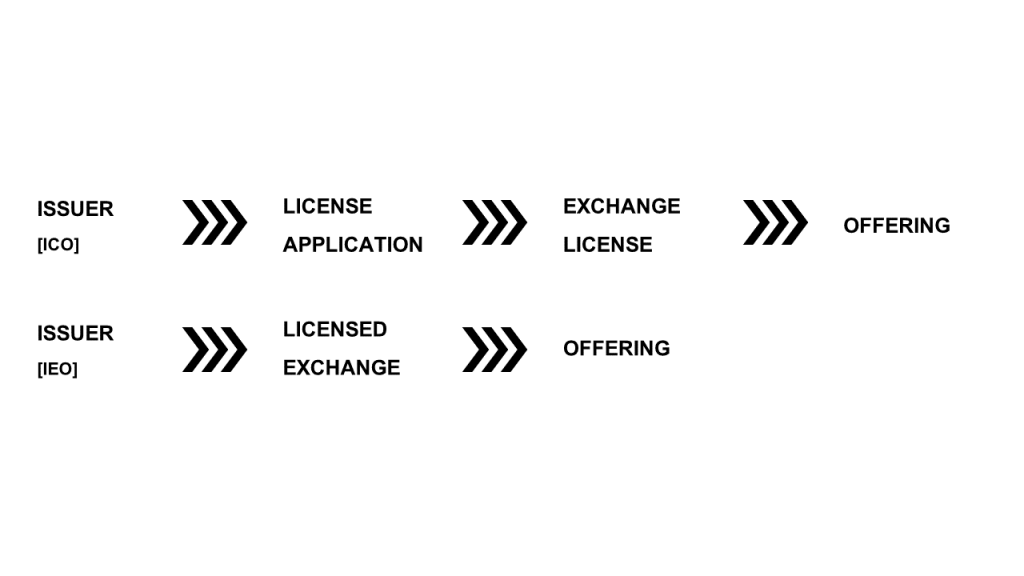

Tokens are often used for fundraising purposes. In this section, we take a closer look at fundraising via initial coin offerings (ICOs), initial exchange offerings (IEOs), and security token offerings (STOs).

The offering of utility tokens for fundraising purposes is commonly known as ICO. Under the PSA, the offering of new tokens in exchange for fiat or cryptocurrencies is considered a crypto asset exchange service.[19] An issuer must therefore either register as a crypto asset exchange service provider[20] or sell his tokens via one of the registered exchanges. In the latter case, the exchange may either act as an intermediary or buy and sell the tokens on its own account.[21]

Excursion – Registration as crypto asset exchange

To register as a crypto asset exchange, companies must meet certain criteria. Local companies must be incorporated as a stock company[22] and have a minimum capital of JPY 10 million[23]. An exchange must further ensure that its net assets do not fall below the amount of users’ funds that are stored in a hot wallet.[24]

Aside from this, crypto asset exchanges must implement corporate governance and security systems that ensure fair dealing on the exchange and reduce operational risks.[25] The latter includes the separation of funds – both for crypto assets[26] and fiat currencies[27] – and the proper management of users’ funds held by the exchange (for more details, see section 4.1 below). Crypto asset exchanges violating their obligations under the PSA are subject to fines of up to JPY 3 million.[28]

While foreign crypto asset exchanges are generally able to register and operate in Japan, none of the 23 registered exchanges is currently a foreign exchange.[29]

Under the ICO regulations of the Japan Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA), an issuer who has successfully applied for a crypto asset exchange license must analyze its internal control and the feasibility of the target business comprehensively before launching its ICO.[30] The analysis must be based on certain documents, including the issuer’s financial statements, material agreements, business plan, whitepaper, and other documents deemed necessary by the issuer.[31] The results of the analysis must be submitted to the JVCEA for final review.[32] Only if the JVCEA does not raise any objections, the issuer may launch its ICO in Japan[33] after giving notice to the FSA[34].

When selling tokens to the broader public, an issuer must disclose a wide variety of information to the public in order to allow investors to make an informed decision. This includes among others:[35]

Once the ICO is completed, the issuer must provide token holders with sales data, including information on the number of tokens issued and the total amount collected.[36] Token issuers are further subject to ongoing disclosure and must publish data about the status of the project and market value of the tokens at regular intervals.[37] This generally applies for a period of five years unless the protection of users is not compromised, and the issuer has informed the JVCEA.[38]

An issuer may not use the raised funds for any other purpose than disclosed to investors during the ICO[39] and must manage them separately from its other funds[40]. The private key controlling the raised funds must generally be stored offline.[41] The issuer must further establish an internal control system to prevent the misappropriation of funds by its officers and employees or the theft by third parties.[42]

Registered exchanges that allow other projects to launch their token offerings via their exchange must implement internal control systems to safeguard investors from investing in projects which are not feasible or an outright scam.[43] At the same time, they must ensure that the token issuer has systems in place to prevent inappropriate solicitation of the token sale or the misappropriation of funds.[44]

When assessing whether a token offering can be launched via its platform, an exchange must consider the issuer’s financial situation. To do so, an exchange must review the financial statements of the token issuer and, if possible, conduct a hearing with a certified accounting or auditing firm.[45] The sales price of the newly issued tokens must be determined in accordance with reasonable valuation methods (e.g. surveys on investment demand).[46] Registered exchanges must also ensure that the raised funds do not exceed the amount which is determined in the business plan of the issuer.[47] The results of the overall assessment must be submitted to the JVCEA for final review.[48] If the JVCEA finds that the offering is not feasible, the exchange must not proceed.[49]

To ensure that the trading of tokens is safe, exchanges must audit the smart contract and the blockchain protocol before launching the token sale.[50] The duty to ensure safety does, however, not end with the token sale. Rather, exchanges are required to monitor the system on an ongoing basis and report vulnerabilities to the JVCEA.[51]

Before offering new tokens on their platform, cryptocurrency exchanges must further publish certain information on their homepage. This information is largely identical to the information indicated in section 2.1.1.[52] Following the offering, the cryptocurrency exchange must ensure that the issuer properly maintains the internal control systems and disclosure mechanisms.[53] This does not apply if five years have passed since the offering or where the exchange has informed the JVCEA that investor protection is not compromised if compliance is no longer monitored by the exchange.[54]

Note: If an issuer actively engages in the token sale, this might be considered a crypto asset exchange service by the issuer and trigger registration requirements under the PSA despite selling the tokens via a registered exchange.[55] Whether this is the case must be determined on a case-by-case basis considering the degree of engagement and other factors.

The solicitation of an offer to sell securities in Japan is generally regulated under the FIEA. The term is understood broadly and covers any communication which allows investors to decide whether to purchase or subscribe for the offered securities. While there is no bright-line test, providing information on the terms of an offering is a clear indication of solicitation. As a rule of thumb, the more granular the information, the more likely it is that the marketing is considered a solicitation. Offers via the internet are generally considered a solicitation to invest in securities if they are made through a website that is publicly accessible. The use of the Japanese language is not necessarily required. Only where investors from Japan are effectively excluded from participating in the offer, for example, by geo-blocking or a KYC-process, an offering is not considered a solicitation of an offer to sell securities in Japan. A disclaimer, according to which Japanese investors are excluded from the offer, is not sufficient on its own but may, in combination with other measures, prevent the FIEA to apply.

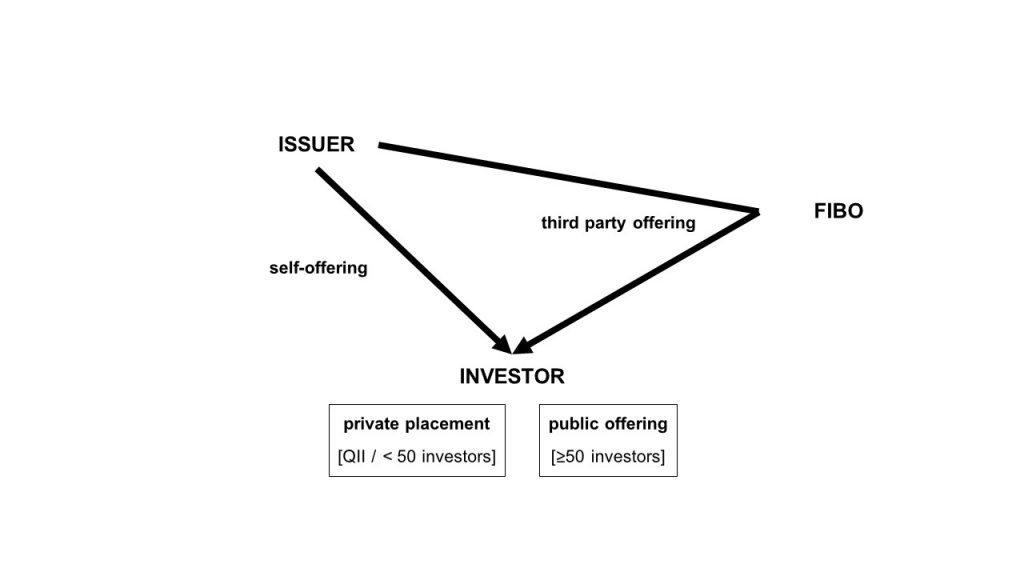

The FIEA distinguishes between public offerings and private placements, self-offerings, and offerings via intermediaries.

The offering of tokenized type I securities and electronically recorded transfer rights is considered a public offering if the tokens are offered to 50 or more investors.[56] Qualified institutional investors (QII) and professional investors as defined in the following section, are not considered when assessing the number of investors.

Public offerings with a total issue price of JPY 100 million (~ USD 915,000) or more must be registered with the FSA[57] and accompanied by a prospectus[58].

Offerings via private placements must not be registered with the FSA. Under the FIEA, the following offers are considered private placements[59]:

3. offers to a small number of investors (< 50)

The definition of QIIs is rather extensive and consists of a long list of examples.[60] The list includes investment corporations, venture capital companies with a stated capital of JPY 500 million or more*, investment limited partnerships as well as special purpose companies*, other legal persons* and individuals* holding securities of at least JPY 1 billion.

Professional investors within the meaning of the FIEA are QIIs, the state, the BoJ, investor protection funds, and other corporations specified by cabinet order. The latter includes among others foreign corporations, specific purpose companies, and listed companies.

Tokens acquired in a private placement by QII or professional investors may not be resold to persons other than QII or professional investors as the case may be. If the tokens are resold in violation of the restrictions on resale, the issuer must file a registration statement with the FSA. This does not apply if the tokens are sold to a small number of investors and are subsequently resold by the initial investors to more than 49 persons.

Companies selling their own tokens in a private placement or public offering do generally not have to register as a FIBO. This applies to both the offering of tokenized type I securities and the offering of electronically recorded transfer rights.

Only where the tokens represent beneficial interests in a (foreign) investment trust, (foreign) mortgage securities, units in (foreign) collective investment schemes, or where another case explicitly mentioned in the FIEA applies, the issuer must register as type II FIBO.[61] The registration requirements apply irrespective of whether the offering is a public offering or a private placement.

Intermediaries who are engaging in the offering of security tokens must register as a type I FIBO under the FIEA.[62]

Tokenized Type I Securities: cryptocurrencies

Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights: utility tokens

Excursion – Other laws

Token issuers must not only comply with the PSA or the FIEA but also with other laws and regulations. The applicable laws do not only depend on the features assigned to a token but also on the way the tokens are distributed. Certain laws may contain form requirements (e.g. physical form), which must be carefully considered when structuring the token and offering. As a general rule, it is however possible to tokenize most assets, including private shares. This topic will be covered in more detail in another article.

Similar to the offering of tokens on the primary market, the trading on the secondary market is subject to different laws depending on whether the token is a crypto asset under the PSA or a tokenized security/electronically recorded transfer right under the FIEA. Crypto asset exchanges licensed under the PSA may not trade security tokens and vice versa.

In this section, we take a closer look at the secondary markets and other key players supporting the trading infrastructure.

Under the PSA crypto asset exchanges and other companies providing crypto asset exchange services must register as crypto asset exchange service providers with the FSA.[63] Crypto asset exchange services are defined broadly and cover the following activities, provided they are carried out as a business:

Given the broad definition of crypto asset exchange services, not only crypto asset exchanges must register with the FSA but also other service providers engaging in crypto-related activities (for custody services see section 4.1 below).

Crypto asset exchanges must implement corporate governance and security systems that ensure fair dealing on the exchange and reduce operational risks. [65] This includes among others to

This list is not exhaustive, and further obligations arise under subsidiary legislation and self-regulation imposed by the Japanese Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA). The self-regulation rules by the JVCEA consistently extend existing regulations and specify in greater detail the obligations under the PSA and AML/CFT regulations.

Crypto asset exchanges and other service providers registered as crypto asset exchange service providers must not engage in activities related to security tokens. These activities are exclusively subject to the FIEA and require additional registrations/licenses.

Excursion: Listing of new tokens

Each token must be analyzed in detail before listing. Where a token violates laws or is likely to be used for criminal activities (incl. money laundering), it must not be listed.[66] This applies in particular for privacy coins for which transactions are anonymous or extremely difficult to track. The results of the analysis must be reported to the board of directors and eventually to the JVCEA.[67] In cases in which the JVCEA does not approve the listing, the respective token must not be listed.[68] The listing of the new token must further be notified to the FSA prior to the token being listed.[69]

Excursion: Margin trading

Crypto asset exchanges providing leverage must inform their users about the risks of margin trading, circuit breakers (if any), as well as the deadline and modalities of repayment.[70] For retail investors, the leverage must not exceed 2x.[71] For corporate clients, there is no fixed maximum leverage. Instead, the ratio may be determined independently by the respective exchange based on a quantitative calculation model or by the JVCEA.[72] Crypto asset exchanges that do not wish to use these ratios may alternatively use the standard leverage of 2x for corporate clients as well.[73] Security deposits may be paid both in fiat and crypto assets. The amount required as a security deposit is calculated each business day.[74] In case of deficiencies, additional payments must be made within 48 hours from the time detecting the deficiency.[75]

Crypto asset exchanges lending fiat to their users must additionally apply for a money lending license under the Money Lending Business Act.[76] Exchanges lending crypto assets do not have to apply for such license.

Given the broad definition of crypto asset exchange services, OTC desks generally seem to be regulated under the PSA at first sight. This applies to both principal desks and agency desks. A closer look at the definition of crypto asset exchange services reveals however, that this is not necessarily the case.

Principal desks: Principal desks buy and sell crypto assets in their own name and on their own account and become counterparty to each transaction. Exchanging crypto assets into fiat currencies and vice versa generally falls under buying and selling of crypto assets as defined in the PSA. The same is true for exchanging crypto assets with other crypto assets.

Agency desks: Agency desks do not become a counterparty to transactions. Rather they act as pure intermediaries and broker deals on behalf of their clients. Such activities constitute intermediary services that are generally covered by the PSA.

The reason why many OTC activities are excluded from the registration requirement under the PSA is that those activities are not performed ‘in the course of business’ as interpreted by the FSA. While the term is generally interpreted broadly, it only covers situations in which the respective party faces the public, i.e. an unspecified large number of people, and does so with a certain continuity.[77] Whether this is the case must be determined on a case-by-case basis. Depending on the facts and circumstances of each case, OTC desks may or may not be covered by the definition of crypto asset exchange services. Engaging in trades with one or a few registered crypto asset exchanges does generally not trigger the license requirement under the PSA. A one-size-fits-all solution does, however, not exist.

Trading activities of professional traders and market makers do not constitute crypto asset exchange services under the PSA. This is due to the fact that proprietary trading is not considered a purchase or sale of crypto assets as a business under the PSA. The reason for this is that the PSA aims to regulate certain activities that pose a risk to the public. It does, however, not intend to regulate all activities related to crypto assets. Trading on regulated exchanges does not pose additional risks to the public and does therefore not fall within the ambit of crypto asset exchange services under the PSA.

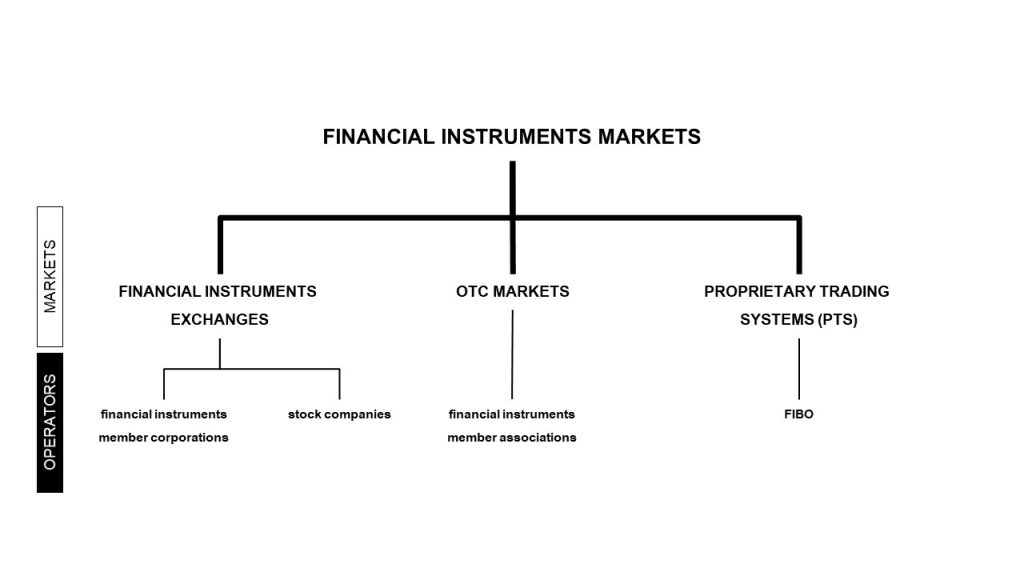

The trading of security tokens on secondary markets is a problem not solved yet. While crypto asset exchanges typically have the infrastructure, they are not allowed to list security tokens on their exchanges. Regulated exchanges, OTC markets, and proprietary trading systems (PTS), as defined in the FIEA, on the other hand, are permitted to trade security tokens but currently lack the required infrastructure.

The FIEA defines a financial instruments market as a market for the purchase and sale of securities and market derivatives.[78] Accordingly, the definition comprises markets for tokenized securities and electronically recorded transfer rights as defined in section 1.2 above. Persons who intend to operate a financial instruments market must obtain a license by the FSA.[79] Something different only applies to the operators of OTC markets and PTS.

Financial Instruments Exchanges: Under the FIEA, a financial instruments exchange may only be established and operated by (i) a financial instruments membership corporation or (ii) a stock company.[80]

A financial instruments member corporation is a legal entity established by a FIBO to operate a financial instruments exchange. Membership in financial instruments member corporations is restricted to FIBOs only.[81] If the number of members falls below six members, the financial instruments member corporation must be dissolved.[82] The same applies if the corporation is not granted a financial instruments exchange license by the FSA.[83] Unlike financial instrument exchanges established by stock companies, exchanges established by financial instruments member corporations may not be operated for profit.[84]

Stock companies establishing a financial instruments exchange must have a stated capital of at least JPY 1 billion.[85] Shareholders are generally prohibited from holding 20 percent or more of the total voting rights.[86]

Out of the five stock exchanges in Japan, two are established as financial instruments member corporations – namely the Fukuoka Stock Exchange (FSE) and the Sapporo Securities Exchange (SSE) – and three as stock companies. The latter comprise the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), the Osaka Stock Exchange (OSE), and the Nagoya Stock Exchange (NSE).

None of the existing exchanges has expressed the intention to establish an exchange for tokenized securities and electronically recorded transfer rights so far. Since this is unlikely to change any time soon, this opens opportunities for challengers in the digital assets space.

OTC Markets: For securities not listed on a financial instruments exchange, the FIEA provides that these securities may be traded on an OTC market established by an authorized financial instruments firms association (SROs).[87] SROs are incorporated by FIBOs as general incorporated associations[88] to ensure fair and orderly trading of securities and derivatives as well as to protect investors[89]. To be recognized as an SRO, the association must be authorized by the FSA.[90] Only then it may carry out the self-regulatory functions laid down in the FIEA[91] and operate an OTC market. Membership in an SRO is limited to FIBOs.[92] Similar to financial instruments exchanges operated by financial instruments member corporations, OTC markets must not conduct business for profit.[93]

Under the FIEA, SROs operating an OTC market are required to register the class and issues of securities traded on the OTC market and make a copy of the register available for public inspection.[94] The SRO must further disclose the trading volume and other particulars for each trading day and issue to its members and the public and report the same to the FSA.[95]

Securities traded on an OTC market may only be traded among the members of the SRO either on their own account or as intermediaries.[96] Depending on its articles of incorporation, an SRO may prohibit its members from taking purchase orders other than from professional investors.[97]

Currently, the only eligible SRO, the Japanese Securities Dealers Association (JSDA), does not operate an OTC market. The Japan STO Association, which currently applies to become the SRO for security tokens and comprising of six major Japanese brokerages, has not expressed the intention to operate an OTC market for tokenized securities or electronically recorded transfer rights yet.

PTS: PTS are similar to Alternative Trading Systems (ATS) in the U.S. and Multilateral Trading Facilities (MTF) in the EU. They were introduced in 1998 to improve investor confidence through competition and to respond to investor demands for more options. Until then, listed securities could only be traded on financial instruments exchanges.

A person operating a PTS conducts financial instruments business within the meaning of the FIEA[98] and must, therefore, register as a type I FIBO with the FSA.[99] According to the FIEA, the prices for securities traded on the PTS must be determined by one of the following methods[100]:

For PTS using a double auction method for price discovery, there are certain restrictions. According to the Enforcement Order, the average daily trading volume of listed securities on PTS may not exceed a certain percentage of the average daily trading volume on all financial instrument exchanges and OTC markets. Broadly speaking, the threshold is 1 percent of the total average daily trading volume for all securities listed on a financial instruments exchange or OTC market[103] and 10 percent of the total average trading volume for single securities listed on a financial instruments exchange or OTC market[104]. PTS exceeding these thresholds must apply for a financial instruments exchange license.

Given the fact that there are no security token markets which are operated by financial instrument exchanges or OTC markets, it is unclear whether PTS can only determine the prices of security tokens in accordance with the methods described under in item (iii) to (v) above.

Discussions are still ongoing, and the outcome is not clear yet. The argument for making PTS subject to the existence of financial instruments exchanges and OTS markets – at least for the methods indicated under items (i), (ii), and (iv) – is that the legislator only intended to increase competition with existing markets, but not to establish an independent framework for secondary markets. In order to maintain a level playing field between traditional securities markets and markets for security tokens, the same must apply to security token markets. On the contrary, it can be argued that the legislator only wanted to prevent liquidity drainage from financial instruments exchanges. For securities not listed on one of the licensed exchanges, such risk does not exist. Unlisted securities, whether tokenized or not, may therefore be traded on PTS, provided of course, the company establishing the PTS complies with other requirements laid down in the FIEA. The same applies to OTC markets. Where none of them exist, the risk of liquidity drainage is effectively non-existent.

Allowing FIBOs to operate PTS would also be in line with developments in other jurisdictions, namely the U.S., where crypto companies have acquired ATS in the past to get access to the desired license and to operate secondary markets for security tokens. Provided, the FSA follows this approach, companies seeking to establish a trading platform for security tokens by way of PTS must register as FIBO or acquire a company already registered. Compared to obtaining the financial instruments exchange license, this would most likely be the way to go for most companies. It is reported that several securities companies intend to jointly establish a new PTS securities company in 2020.

Proprietary trading of securities, and therefore also of tokenized securities and electronically recorded transfer rights, does generally not constitute financial instrument business under the FIEA.[105] Something different applies, however, if the respective entity deals with an unspecified large number of people with a certain degree of continuity.

Intermediary services for OTC trading also fall under the definition of financial instruments business, so that it is necessary to register as a FIBO.

Proprietary trading on financial instruments exchanges and PTS is generally not regulated under the FIEA. This also applies to the vast majority of liquidity providers. An exception is made, however, for high-frequency traders[106] which are not subject to other registration requirements under the FIEA. These traders are required to register with the FSA.[107]

As indicated above, the FIEA distinguishes between market derivatives transactions and OTC derivatives transactions. Market derivatives transactions are such derivatives transactions that are conducted on a financial instruments market. The focus here will be on OTC derivatives transactions, i.e. derivatives transactions, which are performed on a bilateral basis.

Entities engaging in crypto derivatives transactions engage in the financial instruments business as defined in the FIEA[108] and must, therefore, register as a Type I FIBO[109]. An exception is generally made for entities engaging in crypto derivatives transactions with certain counterparties.[110] This includes among others derivative transactions with type I FIBO and qualified institutional investors as defined in the Cabinet Order on Definitions[111] (e.g. financial institutions, high-net-worth individuals). The same applies where the counterparties are equivalent to the aforementioned persons under the laws of another jurisdiction[112] or where the counterparty is a company with a stated capital of JPY 1 billion or more[113]. While this seems to be good news, crypto derivatives are explicitly excluded from the exemption.[114] Companies engaging in crypto derivatives transactions must therefore generally register with the FSA as a type I FIBO.[115] Something different only applies in cases where a FIBO, which conducts an OTC crypto derivatives business in Japan, executes cover transactions with a person engaging in the crypto derivatives business under the laws of another jurisdiction. Provided the foreign entity does not conduct the crypto derivatives transactions from Japan, it does not have to register as a type I FIBO in Japan.[116]

Except from this particular case, companies engaging in crypto derivatives must register as type I FIBO in Japan.

Excursion: Margin trading

The maximum leverage for crypto derivatives transactions is 2x for individuals.[117] For corporations, there is no maximum threshold.[118] Similar to margin trading on crypto asset exchanges, the ratio must be determined by the service provider on a case-by-case basis. In the absence of such a decision, the maximum leverage will be 2x for corporate clients as well.[119]

Crypto assets, tokenized securities, and electronically recorded transfer rights all rely on some form of public key cryptography. The person holding the private key corresponding to the public-key controls the assets. In most cases, the user does not hold the private key himself. Instead, he transfers the control to an exchange or a wallet service provider which introduces new risks. With the amendment of the PSA, the legislator responded to these risks. It is possible that the regulator will introduce similar obligations for security tokens in the future.

The term crypto asset management is understood broadly and covers any activity where a service provider controls the crypto assets of another party.[120] In cases in which the service provider holds the private key(s) of a user, and is able to initiate a transfer of the crypto assets, the services constitute crypto asset management services within the meaning of the PSA and are subject to registration.[121] Given the broad definition of crypto asset management services, the term does not only cover traditional custody solutions, but also certain types of wallets that manage their users’ private keys.

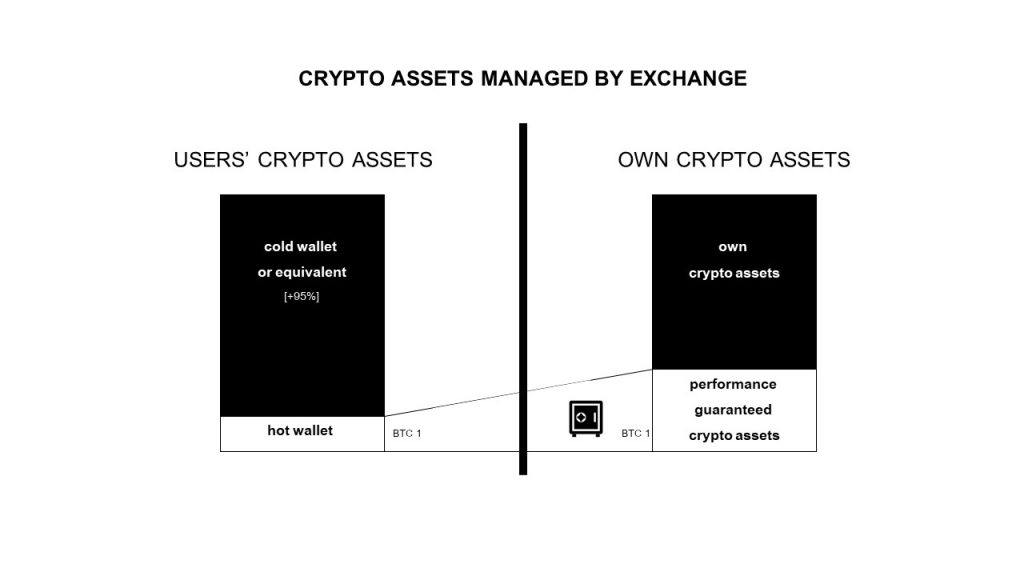

Crypto asset custodians as defined above must not only manage the crypto assets of their users separately from their own[122], but also separately from the other users’ assets to allow easy identification[123]. The private keys controlling the users’ crypto assets must generally be managed via devices which are permanently disconnected from the internet or by other methods that provide a similar level of security.[124] It is well possible that other solutions, such as multi-party computation (MPC), satisfy these requirements. Crypto assets which are held in hot wallets, i.e. where the private keys are stored on devices that are permanently connected to the internet, must be backed by the custodian’s own funds. Under the PSA, custodians are required to hold the same amount of the same crypto asset as their own assets in a cold wallet or in a wallet secured by a method providing a similar level of security, as the funds stored in a hot wallet. By way of example, if a custodian holds 1 BTC of the users’ funds in a hot wallet, it must hold the same amount of BTC as its own assets in a cold wallet. The maximum amount of users’ crypto assets which can be stored in a hot wallet is limited to 5 percent of the total assets under management.[125]

The same applies to crypto asset exchanges, which manage their users’ crypto assets. Additionally, exchanges may entrust their users’ crypto assets to a trust company. Since all of the registered exchanges are centralized exchanges, this applies to all of them. Decentralized exchanges may not have to fulfill these requirements depending on the degree of decentralization. For more information on the regulatory treatment of decentralized exchanges click here.

With respect to exchanges managing their users’ fiat money, they must store these funds separately from their own funds with a trust.[126] In case of insolvency, the funds, both crypto and fiat, are protected, and users of the crypto asset exchange are given priority over the other creditors.

For security tokens, no similar framework exists so far. It is likely that future subsidiary legislation will provide for similar regulations as for crypto assets – at least, in cases where a public blockchain is used. The risk of losing funds is likely smaller, however, since the token will be issued in a more controlled environment. Exchanges being hacked, may simply issue new tokens or ask the issuer to issue new tokens and put the stolen tokens/addresses on a blacklist.

Irrespective of whether a token is a crypto asset under the PSA, a tokenized security or an electronically recorded transfer right under the FIEA, the market is highly regulated in Japan. What seems to be a regulatory overkill, at first sight, is likely to help the market to mature in the mid to long term. This will allow more institutional players to enter the market and to increase their stake in the digital asset space. Companies that intend to operate on the Japanese market are well advised to analyze carefully whether their activities are regulated under Japanese laws. It should be noted that despite the tight regulations, there is still plenty of room for companies to operate on the Japanese market without a license. This is particularly true for companies that are licensed under the laws and regulations of other jurisdictions or who are willing to enter into strategic partnerships with licensed Japanese entities. For some companies, these entities might even become attractive takeover targets.

If you want to learn more or should you need legal or regulatory advice, please feel free to contact us directly under s.saito@innovationlaw.jp.

DISCLAIMER

This article contains a high-level overview and is prepared for general information of our clients and other interested persons. The content has not been confirmed by the relevant authorities, but merely contains information and interpretations that may be reasonably considered in accordance with the applicable laws and regulations. The opinions expressed in this article are our current views and may be subject to change in the future. This article is provided for your convenience only and does not constitute legal advice.

FOOTNOTES

[1] In this article cryptocurrencies, utility tokens, and investment tokens have the following meanings: (i) cryptocurrencies are tokens which are intended to be used as means of payment, (ii) utility tokens give token holders access to an application or service and often serve as a platform-internal currency, (iii) investment tokens allow token holders to participate in the profits of the issuer or the underlying network. Besides these pure forms, hybrid forms exist. The regulatory treatment of these hybrid tokens must be assessed carefully on a case-by-case basis and are therefore not covered by this article.

[2] To learn more about the regulatory treatment of stable coins under Japanese laws, click here.

[3] Article 2(5)(i) PSA.

[4] Article 2(5)(ii) PSA.

[5] Article 2(5) PSA.

[6] See Article 2(1) FIEA.

[7] See Article 2(2) FIEA.

[8] Article 2(3) FIEA.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See Article 9-2(1)(i) and Article 9-2(1)(ii) Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 of the FIEA in connection with Article 17-12 Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[11] See Article 2(5) PSA.

[12] See https://jvcea.or.jp/cms/wp-content/themes/jvcea/images/pdf/statistics/2019

12-KOUKAI-01-FINAL.pdf.

[13] Article 2(24)(iii-2) FIEA.

[14] Article 2(20) FIEA.

[15] Article 2(21) FIEA.

[16] Article 2(22) FIEA.

[17] Article 2(2) FIEA in connection with Article 1-23 Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[18] I-I-2-2(5) Guidelines on Crypto Asset Exchange Business.

[19] For the definition of crypto asset exchange service see Article 2(7) PSA.

[20] Article 63-2 PSA in connection with Article 2(8) and Article 2(7) PSA; see also II-2-2-8-1 Guidelines on Crypto Asset Exchange Business.

[21] See also item 6 concerning Article 2 JVCEA Guidelines on the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[22] Article 63-5(1)(i) PSA.

[23] Article 63-5(1)(iii) PSA in connection with Article 9(1)(i) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers.

[24] Article 25 Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers.

[25] Article 63-5(iv) and (v) PSA.

[26] Article 63-11(2) PSA in connection with Article 27 Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers.

[27] Article 63-11(1) PSA in connection with Article 26 Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers.

[28] See Articles 107 et seq PSA.

[29] A list of all registered exchanges in Japan can be accessed under the following link https://www.fsa.go.jp/menkyo/menkyoj/kasoutuka.pdf.

[30] Article 4(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[31] Article 4(2) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[32] Article 4(4) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[33] Article 4(5) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[34] Article 63-6(1), 63-3(1)(vii) and (viii) PSA.

[35] Article 5(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[36] Article 5(2) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[37] Article 5(3) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Article 6(2) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[40] Article 6(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[41] Article 6(4) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[42] Article 6(5)-(7) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[43] Article 9 et seq. JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[44] Article 15(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[45] Article 15(3) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[46] Article 18(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[47] Article 18(2) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[48] Article 18(3) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[49] Article 15(5) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[50] Article 17(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[51] Article 17(2)-(5) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[52] Article 15(6) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[53] Article 16(1) JVCEA Rules for the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[54] Ibid.

[55] See also item 3 concerning Article 1 JVCEA Guidelines on the Sale of New Crypto Assets.

[56] Article 2(3) FIEA, Article 1-5 Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[57] Article 4(1)(v) FIEA.

[58] Article 13(1) FIEA.

[59] Article 2(3) FIEA.

[60] Article 10 Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[61] Articles 28(2)(iii), 2(8)(vii) FIEA.

[62] Article 28(1) and 29 FIEA.

[63] Article 63-2 PSA.

[64] Article 2(7) PSA.

[65] Article 63-5(iv) and (v) PSA, Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchange Service Providers.

[66] Article 4(1) JVCEA Guidelines on Handling Crypto Assets.

[67] Article 5 JVCEA Guidelines on Handling Crypto Assets.

[68] Article 4(2) JVCEA Guidelines on Handling Crypto Assets.

[69] Article 63-6, 63-3(3)(vii) PSA, Article 12(1) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[70] Article 63-10(2) FIEA, Article 25 Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges, II-2-2-2-2(1) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[71] Article 25(4)(5)(i) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges, II-2-2-2-2(2)(i) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[72] Article 25(4)(5)(ii) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges, Article II-2-2-2-2(2)(ii) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[73] Ibid.

[74] II-2-2-2-2(2)(3) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[75] II-2-2-2-2(2)(4) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[76] Article 3(1) Money Lending Business Act.

[77] I-1-2-2(1) Guidelines: Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[78] Article 2(14) FIEA.

[79] Article 80(1) FIEA.

[80] Article 83-2 FIEA.

[81] Article 91 FIEA.

[82] Article 100(1)(iv) FIEA.

[83] Article 100(1)(vii) FIEA.

[84] Article 97 FIEA.

[85] Article 83-2 FIEA, Article 19 Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[86] Article 103-2 FIEA.

[87] Article 67(2) FIEA.

[88] Article 78(1) FIEA.

[89] Article 67(1) FIEA.

[90] Article 67-2(2) FIEA, Article 78(1) FIEA.

[91] Article 78(2) FIEA.

[92] Article 68(1) FIEA.

[93] Article 67-7 FIEA.

[94] Article 67 FIEA.

[95] Article 67(19) and 67(20) FIEA.

[96] Article 67(2) FIEA.

[97] Article 67(3) FIEA.

[98] Article 2(8)(x) FIEA.

[99] Articles 28(1)(iv), 29 FIEA.

[100] Article 2(8)(x) FIEA.

[101] Article 17(i) Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[102] Article 17(ii) Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[103] Article 1-10(i) Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[104] Article 1-10(ii) Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[105] For the definition of financial instruments business see Article 2(8) FIEA.

[106] For the definition see Article 2(41) FIEA, Article 26 Cabinet Order on Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[107] Article 66-50 FIEA.

[108] Article 2(8)(iv) FIEA.

[109] Articles 28(1)(ii), 29 FIEA.

[110] Article 1-8-6 Order for Enforcement of the FIEA.

[111] Article 1-8-6(1)(ii) Order for Enforcement of the FIEA in connection with Article 15(1) and Article 10 Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[112] Article 1-8-6(1)(ii) FIEA Enforcement Order in connection with Article 15(1) and Article 10 Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[113] Article 1-8-6(1)(ii) FIEA Enforcement Order in connection with Article 15(2) Cabinet Order on Definitions under Article 2 FIEA.

[114] Article 1-8-6(1)(i) FIEA Enforcement Order.

[115] See also IV-3-3-1(3) FIBO guidelines.

[116] Ibid.

[117] Art. 117(41) and (42) Cabinet Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[118] Art. 117(51) and (52) Cabinet Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[119] Art. 117(51) and (52) Cabinet Order on Financial Instruments Business.

[120] I-1-2-2(3) Guidelines on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[121] Article 63-2 PSA in connection with Article 2(7)(4) PSA; I-1-2-2(3) Guidelines on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[122] Article 63-11(2) PSA.

[123] Article 27(1)(i) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[124] Article 63-11(2) PSA in connection with Article 27(3) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges; see also II-2-2-3-2(5) Guidelines on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[125] Article 63-11(2) PSA in connection with Article 27(2) Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

[126] Article 63-11(1) PSA in connection with Article 26 Cabinet Order on Crypto Asset Exchanges.

With the Japanese government declaring the state of emergency shortly before the upcoming annual general meeting (AGM) season and audit firms not being able to finalize their statements, many companies are wondering how to comply with their obligations under the Companies Act (Act).

It should be noted, that the Act does not require the AGM to be held at the end of June. Companies are therefore generally able to postpone their AGM to a later date. This applies to both listed and unlisted companies.

For shareholders to exercise their rights on the AGM, they must be recorded in the shareholders register as of the record date. Since many companies have stipulated a record date in their articles of association which coincides with the end of the financial year this may lead to the result that shareholders participate in the postponed AGM as shareholders, despite having transferred their shares in the meantime. Companies that want to avoid such a situation may therefore decide to hold the AGM at the originally intended date and consider any of the following approaches:

Alternative 1 – Adjournment: A company may decide to hold the AGM at the originally scheduled date, elect the directors and resolve other timely matters on that date. Except from this, the meeting will be adjourned. In the following meeting the financial statements and audit reports will then be discussed and approved by the shareholders.

Alternative 2 – Hybrid-Type Virtual Shareholder Meeting: While it is not possible to replace a physical shareholder meeting by a virtual shareholder meeting, it is possible to use some hybrid models. More recently, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) issued interpretative guidelines stating that it is possible to hold so-called hybrid-type virtual shareholder meetings. These are shareholder meetings that can be attended both physically and virtually. In general, there are two types of hybrid shareholder meetings, (i) hybrid participatory virtual shareholder meetings and (ii) hybrid observational virtual shareholder meetings. In both cases, a physical meeting must be held. The virtual participation is only supplementary.

In a hybrid participatory virtual shareholder meeting, shareholders can exercise their shareholders’ rights almost to the same extent as if they were attending the meeting physically. In a hybrid observational virtual shareholder meeting, shareholders attending the meeting online are limited to an observational role. A company may choose freely between both options.

The following table shows the rights a shareholder has who attends the AGM online:

| hybrid participatory virtual shareholder meetings | hybrid observational virtual shareholder meetings | |

| ask questions | yes | no |

| exercise voting rights | yes | no (only via mail or electronic means prior to the AGM or by proxy) |

| vote on motions | no, due to administrative difficulties | no |

Since it is necessary to identify all attending shareholders on the day of the AGM, certain measures must be implemented in case of a hybrid virtual general meeting. According to the guidelines by METI it is sufficient if a company sends voting forms together with an ID and password to its shareholders prior the AGM, so that shareholders can freely choose whether they want to attend physically or online. When attending online, a shareholder must use the ID and the password to log in and to attend the meeting online. If the ID and the password are used by a person other than the shareholder, the logged in person attending the shareholder meeting is considered the shareholder himself.

Due to administrative burdens and related costs proxies may only attend the physical meeting on behalf of the shareholder.

Some of our clients have decided to hold hybrid virtual meetings this year. As it is the first time companies make use of this model there is no established practice yet. We are monitoring the developments in this field and actively participate in discussions with other industry stakeholders and METI. We expect that there will be further developments in the not so distant future and will update you accordingly.

There is no legal definition of STOs in Japan. STOs are however commonly understood as the issuance of digital tokens that constitute securities under the applicable laws in order to raise capital.

It should be noted, that the definition of securities varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

For the purposes of this article security tokens are defined as digital tokens that have profit rights attached or which can be redeemed for more than 100 percent of the principal amount in money, virtual currencies or other assets.

There have not been any public offerings of security tokens in Japan yet. There are cases however, in which companies sold security tokens to qualified institutional investors (QII) in a private placement. We expect increased activities once the amended Payment Services Act (PSA) and Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) enter into force.

Under the current framework, STOs fall within the scope of the PSA and FIEA at the same time. As a result, persons involved in an STO must comply with both the PSA and FIEA.

The Financial Services Agency (FSA) interprets the term virtual currency broadly. Tokens issued in an ICO are generally covered.

STOs are considered a type of ICOs. Tokens issued in a STO therefore fall under the PSA as well.

The issuer of tokens must either register as Virtual Currency Exchange Service Provider or sell his tokens through one of the registered exchanges.

Registration is cumbersome and expensive. In the current environment, it is not realistic for token issuers to register as a Virtual Currency Exchange Service Provider.

At the moment it is also not possible to sell tokens through one of the registered exchanges. With the Japan Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA) publishing draft guidelines on ICOs, this is likely to change in the near future. Provided the guidelines are approved, token issuers will soon be able to sell their tokens via one of the registered exchanges.

Security tokens as defined in this article are explicitly excluded from the JVCEA guidelines.

Under the existing framework, registered exchanges must notify the FSA about the listing of new tokens. The notification has become a de facto approval by the FSA in practice. No tokens have been listed on registered exchanges since late 2017.

Tokens without profit participation rights attached are generally not covered by the FIEA. Security tokens as defined under item 1 above may however be classified as securities under the FIEA. Security tokens that do not represent traditional securities such as shares or bonds may fall under the definition of collective investment schemes (CIS). To be classified as CIS all of the following requirements must be fulfilled:

Cases where tokens are issued in exchange for bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies instead of fiat currencies are not covered at present.

In March this year, the Cabinet submitted a bill revising the PSA and FIEA to the Diet. The Diet approved the bill on 31 May 2019. With the amendments entering into force early next year, the term “virtual currency” will be replaced by the term “crypto assets” and regulations for registered exchanges will be tightened. In addition, Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights as defined in the FIEA will be explicitly excluded from the definition of crypto assets and exclusively be covered by the FIEA.

| Oct 2019 – end 2019 | FSA publishes Cabinet Order as subsidiary legislation and makes it available for public comment. Public comments and final orders will follow two to three months later (end of 2019 to March 2020). |

| ~May 2020 | Amended laws enter into force. |

After the amendments enter into force, most security tokens will exclusively be covered by the FIEA. Only in rare occasions, the PSA might apply at the same time.

The legal term for security tokens under the new FIEA is Electronically Recorded Transfer Right. In order to classify a token as Electronically Recorded Transfer Right a token must fulfill all of the following requirements:

Tokens classified as Electronically Recorded Transfer Right are considered Type I Securities. The implications of such classification are discussed in further detail in the following sections.

In case any of the requirements from (2) to (4) are not fulfilled, a token is considered a type II security. Tokens for which the transferability is technically restricted may fall under the exemption in item (4) above. However, it is unclear at this point, which cases will be covered by the Cabinet Order.

No, tokenized shares or bonds are Type I Securities and not Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights under the FIEA. In practice, this does not make a difference however, since Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights are treated as Type I Securities. As such both are subject to the same disclosure requirements under the FIEA.

Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights are explicitly excluded from the definition of crypto assets under the amended Payment Services Act (PSA). Tokens that do not fall under the definition of Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights due to liquidity constraints may, in theory, be subject to both the PSA and FIEA. It must be noted, however, that in case of liquidity constraints, the token can also not be exchanged with other tokens or fiat currencies. As such, it is unlikely that the token is considered a crypto asset under the PSA.

Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights are considered Type I Securities under the FIEA. As such they are generally subject to disclosure requirements at the time of issuance (e.g. registration documents, prospectus) and subsequently (e.g. quarterly reports, extraordinary reports).

The exact information that must be disclosed at the time of offering will be stipulated by Cabinet Order in the future. In general, the preparation of a prospectus and other disclosure documents takes a considerable amount of time.

Private placements are generally exempted from disclosure requirements.

A public offering is an offering of newly issued Type I securities to at least 50 persons which is not considered a private placement.

The following offers are considered private placements of Type I Securities under the FIEA:

Private placements to QII: Offers to QII with the resale restriction under 5.7 below are considered private placements under the FIEA.

Private placements to specified investors: Offers to specified investors with the resale restriction under 5.7 below are considered private placements under the FIEA. Offers to specified investors other than QII can only be made by financial instruments business operators (FIBO).

Private placements to a small number of investors: Solicitations to less than 50 investors (QII can be excluded from this number) with the resale restriction under 5.7 below are considered private placements under the FIEA.

Private placements to QII: In general securities acquired in a private placement may not be resold to persons other than QII. The exact nature of the restrictions varies depending on the type of securities. In case securities are sold in violation of the restrictions on resale, the issuer must file a registration statement with the FSA.

Private placements to specified investors: In general securities issued in a private placement to specified investors may not be resold to other persons than specified investors. Where securities are sold in violation of these restrictions, the issuer must file a registration statement with the FSA.

Small number of investors: Resale restrictions vary depending on the type of securities. While there are no resale restrictions for shares, restrictions apply to the resale of share options and other securities. In these cases, the securities may only be transferred in bulk. Where the total number of units is less than 50, the units may not be split.

In general, the same restrictions apply. Security tokens are considered “other securities” under the current FIEA Enforcement Order and Cabinet Order to which the same resale restrictions apply in case of private placements. It is possible that additional requirements, such as the implementation of technical measures, will be introduced in the future.

A person engaging in the business of buying and selling security tokens (incl. the provision of intermediary services, public offerings and private placements) must generally register as a FIBO under the FIEA.

There are no restrictions for the self-solicitation of tokens that are classified as traditional type I securities such as stocks. Regulations apply however for the self-solicitation of units in a CIS. Persons offering their own security tokens, which qualify as units in a CIS, must register as type II FIBO even if such units are considered Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights.

Intermediaries in the sale and purchase of security tokens must register as type I FIBO. This applies irrespective of whether the tokens are classified as traditional type I securities or Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights.

Persons intending to operate a security token exchange must obtain a Financial Instrument Market License or the approval as proprietary trading system (PTS), depending on the business model. Since it is difficult to obtain the said license or to registers as PTS, we expect that most of the secondary trading will initially occur OTC.

Under the Japanese Civil Code the transfer of contractual rights generally requires an agreement between the assignor and assignee as well as the consent of the counterparty to the contract. This should be reflected in the contract documentation for the STO.

Electronically Recorded Transfer Rights are not stock or bonds. The provisions on the issuance of stock and bonds under the Companies Act do therefore not apply. If the rights of an anonymous partnership or other funds are tokenized, an approval by the general meeting of shareholders is not necessary. Since the tokenization of an anonymous partnership can be considered an important decision a board resolution is however required.

No, this is not necessary. From a management perspective, it is advisable to issue only tokens that do not harm the rights of existing shareholders.

Listed companies must disclose the issuance of security tokens in a timely manner. What kind

of information must be disclosed should be coordinated with the respective exchange

DISCLAIMER

This article contains a high-level overview and is prepared for general information of our clients and other interested persons. The content has not been confirmed by the relevant authorities, but merely contains information and interpretations that may be reasonably considered in accordance with the applicable laws and regulations. The opinions expressed in this article are our current views and may be subject to change in the future. This article is provided for your convenience only and does not constitute legal advice.

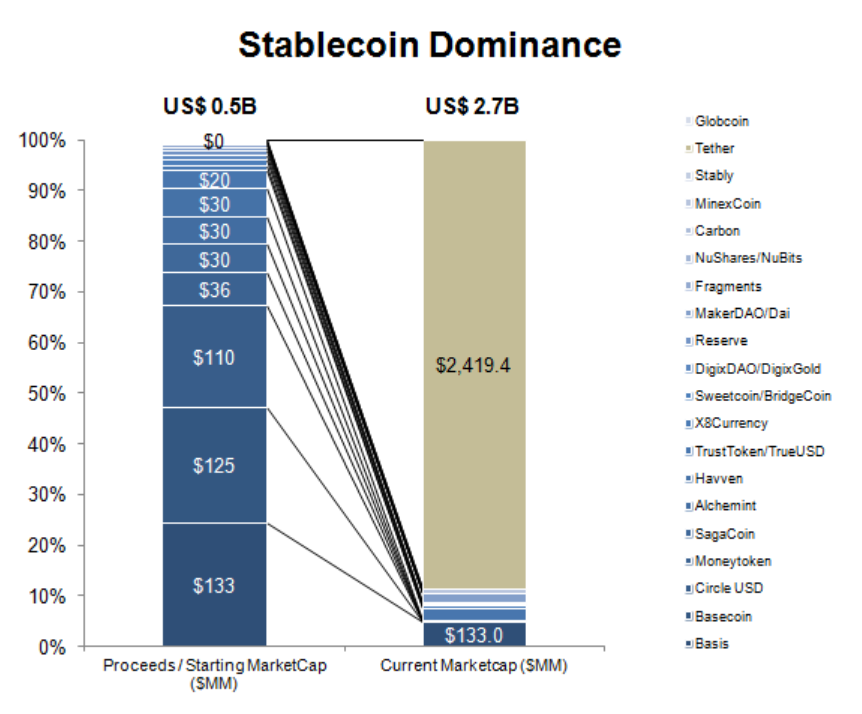

According to proponents of stable coins, the volatility of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is one of the biggest barriers to mainstream adoption. Stable coins come with the promise to remove these barriers and are therefore praised as the Holy Grail of Crypto. As of the time of writing, stable coins have reached a market capitalization of USD 4 billion. With the rise of decentralized exchanges without links to the traditional financial system, this amount is likely to increase. Despite the overall success of stable coins globally, none of the big projects has been listed on cryptocurrency exchanges in Japan yet.

In the following, we will explain the different types of stable coins and assess the regulatory environment for each model in more detail.

“Stable coin” is an umbrella term describing crypto assets which are stable relative to a predetermined asset – most commonly the US Dollar. In general, there are three types of stable coins: IOU[1] models, on-chain collateralized models, and seigniorage models.

The examples used in this article are for illustrative purposes only.

IOU models currently dominate the stable coin landscape. This is likely to be attributed to the simplicity and clarity of the model. While a look under the hood shows significant differences in design, all IOU models have in common that there is a central entity that issues tokens which represent a redeemable certificate against the issuer for the benefit of the token holder. To ensure the stability of the token, each token is generally fully backed by a fiat currency or another real-world asset. In few cases, a mere guarantee is made by the issuer to buy back tokens at a predetermined price.

In the case of TrueUSD, tokens are freshly minted when users wire funds to a third-party escrow account and burned when US Dollars are redeemed. This mechanism ensures parity between TrueUSD in circulation and the US Dollars held in escrow accounts. A similar mechanism is deployed by Libra[2], where each token is backed by reserves. New tokens are only minted if authorized resellers inject money into the reserves. Conversely, tokens are destroyed when demand contracts. Since the tokens are backed by a basket of fiat currencies rather than a single fiat currency, there will be fluctuations in price as a result of FX market movements.

Tether – by far the most successful but also one of the most controversial stable coin projects[3] – mints new tokens irrespective of user payments. Yet, similar to TrueUSD, the project promises to maintain a one-to-one ratio between its stable coin USDTether and US Dollars held as reserves.

In Japan, a project known as JPYZ was launched in 2017. Unlike the projects mentioned above, JPYZ are not backed by Japanese yen. Parity with JPY is maintained by a guarantee of the issuing entity to make a purchase order of each token for a price of JPY 1 on listed exchanges. The project is described as a social experiment and has not scaled as much as some of the USD stable coins yet.

Token(s): stable coin

On-chain collateralized models require a complex system of smart contracts, different kinds of tokens, oracles, and external actors to ensure their coin remains stable. MakerDAO, for example, requests its users to transfer crypto assets to a smart contract. The smart contract then issues a loan in the form of stable coins (DAI) and effectively locks the collateral in the smart contract until the loan is paid off.

The target price for DAI is set to USD 1 and used to determine the value of collaterals locked in the smart contract. Given the volatility of the collateral MakerDAO requires all loans to be over-collateralized. Where the collateral-to-debt ratio falls below a certain threshold, the position is automatically liquidated, and the collaterals sold on the market. This ensures that DAI always remains stable relative to the US Dollar.

A second type of token – Maker Token (MKR) – is used for the payment of a stability fee. This fee must be paid in addition to the debt in order to release the collateral from the smart contract. MKR tokens further play a central role in the governance of the Maker Platform, by giving each token holder voting rights (e.g. for the appointment of oracles and the determination of the stability fee).

Main tokens: stable coin, hybrid governance / utility token

Seigniorage models are based on the quantity theory of money. To keep the token price stable compared to a reference currency or another reference value, the token supply is adjusted continuously depending on demand and supply. In phases of inflation, the token supply is contracted automatically to bring prices back to the original level. Conversely, the token supply is expanded in phases of deflation.

In the case of Basis[4] the stable coins (Basis) were pegged to the US Dollar. To maintain the peg, the Basis supply was controlled by additional tokens – share tokens and bond tokens. The bond tokens were auctioned off for prices less than one Basis when the supply had to contract. When the system determined that an expansion of the Basis supply became necessary, holders of bond tokens received one Basis for each bond token in a first-in-first-out order. In cases where the bond tokens were not sufficient to expand the token supply, holders of share tokens participated in the issuance of new Basis according to their overall share tokens in the system.

Main tokens: stable coin, bond tokens, share tokens

In the following, we will analyze each model in more detail. Where a model involves more than one token, the additional tokens are considered in our analysis as well.

In an IOU model, a single token – the stable coin – is issued. Depending on the design of the token and the underlying business model, a token might either be classified as a prepaid payment instrument, money order, or virtual currency.

The Payment Services Act (‘PSA’) defines prepaid payment instruments inter alia as signs which are recorded electronically in exchange for consideration. Depending on whether the signs can be used for the purchase of goods and services from the issuer or the issuer and persons designated by the issuer, a prepaid payment instrument may either be classified as a prepaid payment instrument for own business or a prepaid payment instrument for third-party business.

In most cases, stable coins do not constitute prepaid payment instruments since they are not issued for the purchase of goods and services within a predefined ecosystem. Instead, they can be accepted for payment – irrespective of contractual relationships with the issuer – by anyone. The mere fact that stable coins can only be redeemed by users who have passed the know-your-customer procedure of the issuer does not lead to different results.

Also, the fact that stable coins issued under the IOU model can generally be redeemed for fiat currency speaks against the classification as a prepaid payment instrument. According to the PSA “issuers of prepaid payment instruments must not make any refunds” except in cases specified in the PSA. Typical cases are the redemption of small amounts and cases where the user cannot continue to use the prepaid payment instrument for inevitable reasons (e.g. discontinuation of the business of the issuer).

Stable coins issued in exchange for fiat currencies that can be redeemed by the token holder are likely to be classified as a money order. While there is no legal definition in the PSA or the Banking Act, a money order is commonly understood as a payment order for a certain amount of money. The amount indicated on the money order must generally be paid upfront and can only be cashed by the person shown as the recipient in the money order. Tokens issued under the IOU model do however, not include a recipient. Instead, they may be redeemed by anyone who owns the private key corresponding to the respective token. As such stable coins are comparable to blank money orders with enhanced safety features and increased negotiability. Even slight changes to the underlying business model may lead to different results (see item 2.1.3 below).

Tokens that are classified as money orders are not regulated themselves. For entities involved in the sale, transfer or redemption of the token, the law may require, however, that these entities hold a banking license or are registered as a transfer service provider under the PSA.

In some cases, stable coins issued under the IOU model may also constitute virtual currencies. The PSA distinguishes between Type I and Type II virtual currencies. Type I virtual currencies are defined broadly as property value that

Type II virtual currencies are defined as values that can be mutually exchanged for Type I virtual currencies with unspecified persons and which can be transferred electronically.

Currencies and currency denominated assets are explicitly excluded from Type I and Type II virtual currencies.

Since stable coins issued under an IOU model are likely to be classified as currency denominated assets, they cannot be classified as Type I or Type II virtual currencies.

Even slight changes to the underlying business model may, however, lead to a completely different result. This can be seen from JPYZ. Different from the other IOU models, JPYZ tokens are not refunded by the issuing entity but bought back for a guaranteed price through an exchange – JPY 1 for JPYZ 1. This has led the Financial Services Agency (FSA) to classify JPYZ as virtual currencies within the meaning of the PSA.

Entities issuing stable coins that constitute virtual currencies must register as a virtual currency exchange business in Japan.

On-chain collateralized models typically involve more than one token. In the case of MakerDAO, this includes a stable coin and a hybrid utility governance token.

Stable coins issued under an on-chain collateralized model are likely to be categorized at least as Type II virtual currencies. This is due to the fact that they can be mutually exchanged with Type I virtual currencies with unspecified persons. The mere fact that there is a soft peg to the US Dollar or other fiat currencies does not make the stable coin a currency denominated asset. The peg serves as a stability mechanism only and does not contain the promise to make a refund in US Dollar or another fiat currency.

Governance tokens which can typically be mutually exchanged with Type I virtual currencies are generally considered Type II virtual currencies.

Stable coins issued under seigniorage models are likely to be classified as virtual currency Type II. Insofar, reference is made to the explanations under item 2.2. above.

Bond and share tokens necessary for the adjustments to the money supply may be classified as securities under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (‘FIEA’). The marketing of such securities generally requires registration as Financial Instruments Business Service under the FIEA.

Where bond and share tokens can be mutually exchanged with Type I virtual currencies, they are further deemed Type II virtual currencies.

A listing on one of the registered cryptocurrency exchanges is not possible for securities under the current regulations.

This article only gives a high-level overview of the current regulatory environment for different stable coin models in Japan. Even slight changes to the token design or underlying business model may lead to completely different results. Issuers of stable coins are therefore well advised to consider their model carefully – and in cases where the stable coin is on the market already to assess whether the stable coin can be marketed and eventually listed in Japan.

If you want to learn more or should you need legal or regulatory advice, please feel free to contact us directly under s.saito@innovationlaw.jp.

DISCLAIMER

The stable coins mentioned in this article are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the article not all details of the token design and underlying business model have been considered, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project. By no means, the explanations should be understood as a legal opinion regarding the stable coins mentioned in this article.

FOOTNOTES

[1] IOU stands for I owe you.

[2] Libra has not gone online yet and only published its whitepaper recently.

[3] According to the terms and conditions of Tether, “the composition of the reserves used to back tether tokens is within the sole control and absolute discretion of Tether” and “may include other assets and receivables from loans made by Tether to third parties, which may include affiliated entities”. Tether has not provided audited accounts yet and has repeatedly been accused of market manipulation in the past.

[4] On December 13, 2018, Basis announced that US regulations had a serious negative impact on their ability to launch Basis and forced them to shut down before the project was launched. All funds were returned to their investors.

Japan’s Financial Services Agency (the “FSA”) imminently contemplates reforming the crypto regulations to address the problems that arose after Phase 1 of the virtual currency legislation, effected in April 2017. The FSA published a draft bill for the amendment of the virtual currency regulation on March 15, 2019. Stated below is our current understanding of the amendment. Please note that as the national diets will discuss the draft from now and the FSA will draft subordinated provisions of the laws from now, there is still some uncertainty on the amendment, and our analysis is expressly subject to changes in the future.

The Payment Services Act (the “PSA”) and the Act on Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds (the “AML Act”), as amended together in April 2017, are the base of the Phase 1 virtual currency legislation, as supplemented by the related ordinances, orders, and guidelines (most notably the Guidelines for Administrative processes concerning virtual currency exchange service providers (FSA Guidelines)).

The PSA (so amended in 2017) is an act which currently regulates a virtual currency exchange. The PSA stipulates “Virtual Currency,” “Virtual Currency Exchange Service,” and “Virtual Currency Exchange Service Provider” therein. It requires registration of Virtual Currency Exchange Service Providers, and the FSA regulates and supervises them.

The PSA will be amended and involve more detailed regulation on crypto exchanges and new regulation on crypto custody business.

The FIEA regulates financial instruments, which typically include

securities/derivatives, financial instruments, exchange business and operators thereof.

Currently, virtual currency does not fall under securities, in principle. Some STO tokens fall under collective investment schemes (funds) that are securities (see item 7 below).

Margin trading of virtual currencies (NDF, leveraged trades, physically settledtrades by loans in virtual currency) are currently non-regulated through FIEA.

The Act on Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds (so amended in 2017) has subjected VC exchanges to the AML/CTF regulations and imposed such duties as customer identity verification at the time of the transaction, etc.

In April 2018, sixteen (16) registered VC exchanges joined to establish a selfregulatory organization, the Japan Virtual Currency Exchange Association (the “JVCEA”). In October 2018, the JVCEA got certified by FSA as a Certified Association for Payment Service Providers under PSA.

JVCEA established the self-regulation rules in furtherance of the existing regulations that are based on, amongst others, PSA, AML Law and FSA Guidelines with a view to better protect users. Examples of self-regulation are as follows.

Currently, to earn a VC exchange license is perceived to be staggeringly