Earlier last year, the Japanese government started to tighten the rules on foreign direct investments (FDI) by adding, among others, certain sectors in the information and communication technology and software development to the list of restricted industries. Foreign investments in companies that operate in these sectors are generally subject to pre-transactional approval by the relevant authorities if they exceed certain thresholds. With the latest amendments, the legislator lowered the threshold for the acquisition of shares in listed companies from 10% to 1%. At the same time, exemptions were introduced allowing foreign investors under certain conditions to buy shares above these thresholds without obtaining prior approval.

The changes entered into force on May 8, 2020 and apply to all investments on or after June 7, 2020.

The Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (Act) aims “to enable the proper development for foreign transactions and the maintenance of peace and security in Japan”. To ensure that these goals are achieved, the Act limits among others foreign investments in sectors which are vital to national security (e.g. infrastructure, aviation, nuclear technology).

Only in 2019, the legislator added the ICT industry, etc. to the list of restricted sectors. The move reflected the increasing importance of those industries in a national security context and was largely in line with developments in other jurisdictions.

This time, the legislator extended the definition of foreign investors and lowered the threshold for investments in listed companies irrespective of their industry. At the same time, some exemptions to the pre-transactional approval requirement were introduced for certain types of investors.

The Act defines foreign investors as (i) individuals who are non-residents, (ii) entities established under foreign laws or having their principal office in a foreign state, (iii) Japanese entities which are directly/indirectly controlled by persons set forth in item (i) and (ii), and (iv) entities in which the majority of directors are persons set forth in item (i). A person is considered to control an entity within the meaning of item (iii) if it holds 50% or more of the voting rights in a company. Whether the voting rights are held directly or through other entities controlled by the respective person is irrelevant.

With the latest amendment (iv) partnership-type investment funds were added to the definition of foreign investors provided, however, 50% or more of the total capital of the fund was contributed by persons indicated under item (i) and (ii) above.

The term “inward direct investment or equivalent action” is defined broadly. It includes (i) the acquisition of shares (both on primary and secondary markets), (ii) consenting to certain substantial changes to a company’s scope of business after the acquisition of the shares, (iii) the establishment of a branch offices, (iv) the issuance of loans of at least JPY 100 million and a term of one or more years[1], and (v) the succession of business by means of business transfer, absorption type company split or merger.

The acquisition of shares in a listed company is only considered a direct investment under the Act if the investor holds at least 1% of the outstanding shares or voting rights following the transaction. Whether the investor holds the shares or voting rights directly or through closely related persons is irrelevant. The definition of closely related persons is rather complex. At its core, it includes affiliates and business partners of a foreign investor where the investor is a company, and relatives of the investor if the investor is a natural person.

Out of the 1465 sectors under the Japan Standard Industrial Classification 155 sectors – including pharmaceuticals and medical devices for the containment of infectious diseases such as COVID-19 as per recent amendment – are designated business sectors under the regulations. As discussed in more detail in section 5 below, foreign direct investments into designated business sectors may trigger pre-transactional approval requirements.

The regulations further distinguish between core-designated sectors and non-core sectors. While some industries belong exclusively to core or non-core designated sectors, others may be covered by both.

Listed Companies: The Ministry of Finance (MoF) published an exhaustive list indicating for all listed companies in Japan, whether their activities fall within non-designated sectors, designated sectors other than core sectors, or core sectors. The full list can be found on the website of the MoF.

Unlisted Companies: For unlisted and private companies, it is necessary to assess in each case whether the relevant business falls within the designated sectors – and if so under the non-core or core sector – as different notification requirements apply for exempted investors. The full list of designated sectors can be found on the website of the MoF as well (only Japanese).[2]

Foreign investments in companies operating in designated sectors are generally subject to pre-transactional approval by the relevant authorities via the Bank of Japan (BoJ). For listed companies, the approval requirement is triggered when an investor holds 1% of the outstanding shares or voting rights subsequent to the investment either on his own or together with closely related persons.

For unlisted companies there are no thresholds. Investments in companies operating in the designated sectors are therefore subject to BoJ approval irrespective of the amount invested and the shares or voting rights held following to the investment.

| threshold | |

| listed companies | 1% |

| non-listed companies | n/a |

Investors who fail to obtain pre-transactional approval by the BoJ may be ordered to dispose of all acquired shares.

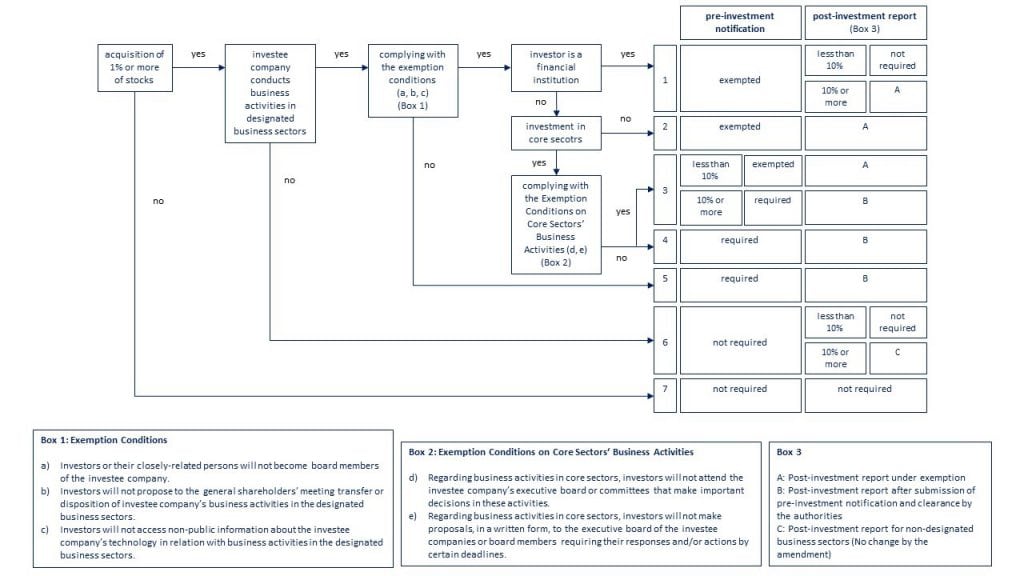

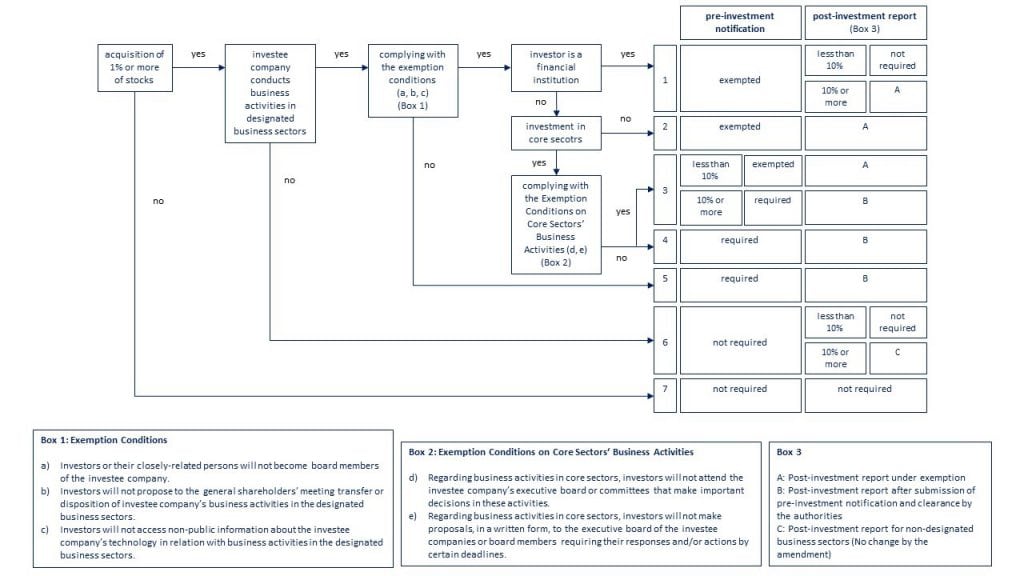

The new regulations provide for exemptions from the pre-transactional approval requirement for certain types of investors but only if these investors meet additional criteria.

The blanket exemption is available to foreign financial institutions which are subject to Japanese regulations or equivalent foreign regulations. The definition includes, banks, securities firms, insurance companies, asset management companies, trust companies, registered investment companies, as well as high-frequency traders[3].

In order to qualify for the blanket exemption these entities or closely related persons must

| (a) | not become board members of the investee company |

| (b) | not propose at a general shareholders’ meeting the transfer or disposition of the investee company’s business in the designated sector(s) |

| (c) | not gain access to non-public information about the investee company’s technology concerning the designated sectors. |

Financial institutions complying with these requirements do not have to obtain pre-transactional approval via the BoJ. This applies irrespective of whether the investee company operates in core or non-core designated sectors and irrespective of the number of shares or voting rights held following the investment.

If an exempted investor holds 10% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment, it must however file a post-investment report with the BoJ.

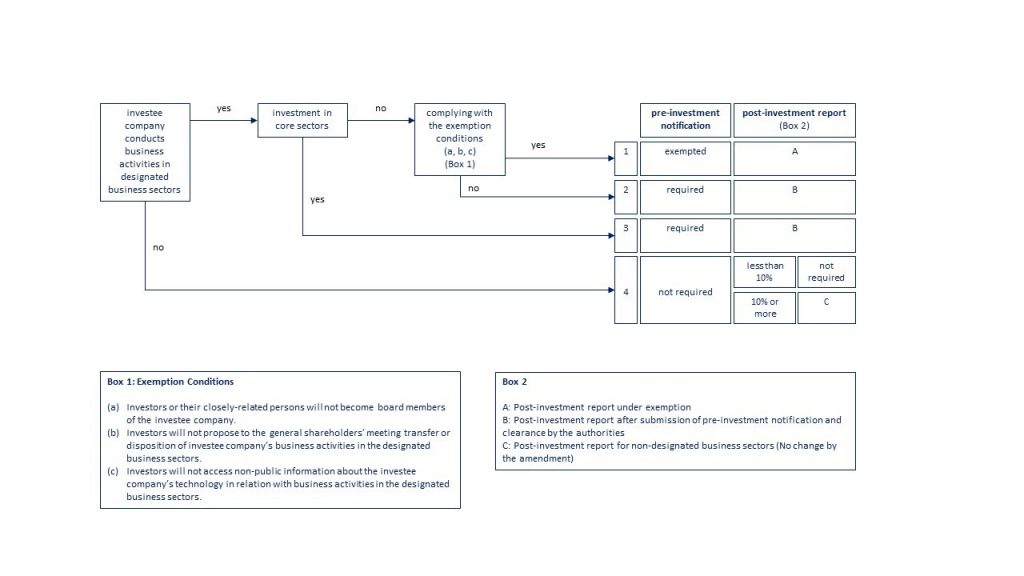

Exemptions from the pre-transactional approval also apply to general investors (including sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds accredited by authorities). In contrast to the blanket exemption, it is necessary to distinguish between investments in companies operating in designated core sectors and companies operating in non-core sectors.

Non-core sectors: Investments in non-core sectors are exempted if the investor meets all the requirements under item (a) to (c) in section 6.1 above. It is however necessary to file a post-investment report, if the investor holds 1% of the shares or voting rights following the investment.

Core sectors: Investments in core sectors may only be exempted if the investor does not hold 10% or more of the shares or voting rights subsequent to the investment. In order to qualify for the exemption an investor must comply with the requirements under item (a) to (c) in section 6.1 above and must

| (d) | not attend the investee company’s executive board or committees that make important decisions on activities in the core sector |

| (e) | not make any proposals in writing to the executive board or board members requiring their responses and/or actions by certain deadlines. |

A post-investment report must also be filed in these cases provided the investor holds 1% or more of the shares[4] or voting rights following the investment.

Please note that a foreign investor is not required to obtain a pre-transactional approval if a company has only indicated restricted activities in its corporate documents (e.g. articles of incorporation, corporate registry) but has not operated in these sectors within 6 months prior to the investment. Even in this case, the foreign investor must however submit a post-investment report if he holds 10% or more of the voting rights of the investee company.

Investments that require pre-transactional approval must be notified to the BoJ before the investment is made. The notification must specify the purpose of the investment, the amount, the time and other information as specified by Cabinet Order. Once the notification is submitted, there is a 30-day waiting period during which the investment must not be executed. In practice the waiting period is generally shortened to 2 weeks. Under certain circumstances, the waiting period may, however, also be extended to a maximum of five months. To avoid unnecessary delays, foreign investors should engage in informal discussions with the relevant authorities prior to filing the notification.

Post-investment reports mainly serve statistical purposes and must be filed within 45 days after the respective investment is made.

Whether the latest amendments negatively affect the readiness of foreign investors to invest in Japanese companies remains to be seen. Given the newly implemented exemptions under the Act, it should however not hamper foreign investment unreasonably.

In any case, investors are well advised to check early whether their investments require pre-transaction approval by the BoJ and if so whether they are exempted. For listed companies this can be checked easily. For unlisted companies, it is necessary to assess in more detail whether the company falls under the designated sectors.

Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions in that regard and should you need our assistance.

[1] Loans issued by banks and other financial institutions in the course of trade are explicitly excluded from the definition.

[2] To see all items please visit https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-1.pdf, https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-2.pdf,https://www.mof.go.jp/

international_policy/gaitame_kawase/fdi/publicnotice1-3.pdf, https://www.mof.go.jp/international_policy/gaitame_

kawase/fdi/index.htm#joubun (accessed 20/07/2020).

[3] High-frequency traders are only eligible for the blanket exemption if they are registered with the Financial Services Agency.

[4] Please note that the foreign investor will have to submit (i) a report after the investor holds 3% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment and (ii) a report for each acquisition after the investor holds 10% or more of the shares or voting rights following the investment.

[5] MOF, Rules and Regulations of the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, p. 16 retrieved from https://www.mof.go.jp/english/international_policy/fdi/kanrenshiryou01_20200424.pdf (accessed 20/07/2020).

[6] Ibid, p. 17.

Mostly unrecognized by mainstream media, DeFi has gained increasing traction over the last few months. Large parts of its growth can be attributed to lending platforms such as Compound, Maker, and Aave, just to name a few. Broadly speaking, users of these platforms receive some form of interest in exchange for locking their assets into a smart contract, which in turn lends them to (other) users. Together with extrinsic rewards paid by these platforms, yields of up to 100 percent are currently possible. The process of optimizing yield through a combination of leverage and rewards is commonly referred to as yield farming and liquidity mining.

In this article, we will discuss the regulatory treatment of lending platforms under Japanese laws. Restrictions for users do not exist. In our next article, we will focus on the opportunities, Compound and other platforms provide to crypto asset exchanges in Japan, which currently face fierce competition and pressure under the new regulations.

The basic concept of yield farming and liquidity mining is to generate passive income from crypto assets. Yield farmers and liquidity miners generally try to put their assets to maximum use by utilizing a combination of lending and borrowing techniques on one or more lending platforms. Apps such as Instadapp help users to bridge different protocols and to leverage the full potential of DeFi by automating large parts of the lending and borrowing activities.

To explain how yield farming and liquidity mining work, we will use Compound, one of the biggest and currently most used platforms, as an example.[1]

In order to earn a yield on Compound, users must lock their assets in a smart contract. In turn, the smart contract issues new tokens (cTokens) at a predefined exchange rate. These tokens allow the user to earn a yield over time and to use them as collateral when borrowing funds via the platform.

cTokens do not provide recurring revenue to their holders. Instead, they represent a share in a pool of assets that constantly grows due to borrowers’ interest payments. With the price of cTokens increasing relative to the locked assets, cTokens generate a yield when used to withdraw the locked assets. The actual amount depends on the compound interests calculated by the protocol based on market dynamics, namely supply and demand.

In addition to the compound yield, lenders currently receive COMP tokens. These tokens allow their holders to propose and vote on changes to the protocol and are actively traded on exchanges. Only with COMP tokens, the current yields are possible at all.

When borrowing funds via Compound, a user must deposit cTokens as collateral. The maximum amount a user can borrow depends on the collateral factor of the deposited asset. This factor is set by COMP token holders. The collateral factor is generally higher for liquid, high-cap assets and lower for illiquid, small-cap assets. The collateral factor of ETH, for example, is currently set at 0.7. A user supplying ETH 100 to the protocol, would therefore be able to borrow up ETH 70 worth of assets via Compound.[3]

Where a user’s borrowing balance exceeds his borrowing capacity due to outstanding interests, the value of collateral falling or the borrowed assets increasing in price, the collateral will be liquidated automatically at a discount to the current market price.

Like lenders, borrowers currently receive an external reward in the form of COMP tokens for using the Compound platform. Every day, approximately 2,880 COMP are distributed – 50 percent to lenders and 50 percent to borrowers.

When analyzing the legal and regulatory environment for DeFi lending activities, it is necessary to break down the lending model into different components. First, it is necessary to analyze the tokens required for the protocol to work. In a second step, the activities involving each of the tokens must be analyzed in more detail. It should be noted, however, that it is not possible to view tokens and activities as separate components, but that it is necessary to consider the interaction between both for the analysis.

Compound and other lending platforms involve a number of different tokens. In the case of Compound, these tokens are (i) ETH and ERC-20 tokens supplied to the protocol, (ii) cTokens which are issued in exchange for the tokens supplied, and (iii) COMP which is issued as a reward and which constitutes the protocol’s governance token.

Under Japanese laws, tokens may either constitute crypto assets under the Payment Services Act (PSA) or electronically recorded transfer rights under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). Tokens neither covered by the definition of crypto assets nor electronically recorded transfer rights may not be regulated at all.

The PSA distinguishes between type I crypto assets and type II crypto assets. Type I crypto assets are proprietary values that can (i) be used for purchasing goods and services from unspecified persons, (ii) purchased from and sold to unspecified persons acting as counterparties, (iii) and transferred electronically.

Type II crypto assets are property values that can (i) be mutually exchanged with unspecified persons for type I crypto assets and (ii) transferred electronically. Currency denominated assets such as fiat currencies and electronically recorded transfer rights are explicitly excluded from the definition of both type I and type II crypto assets.

The definition of electronically recorded transfer rights was added to the FIEA with the latest amendment. It covers electronically recorded values that represent type II securities which can be transferred electronically, and which do not have liquidity constraints.

Currently, most platforms, including Compound, allow users to deposit ETH, certain ERC-20 utility tokens[4], and different kinds of stable coins.

ETH is a typical type I crypto asset. ERC-20 utility tokens generally constitute type II crypto assets as they can easily be exchanged with type I crypto assets. The same most likely applies to wrapped bitcoin as they are currently not used for payment and can only be exchanged with type I crypto assets.

For stable coins, the legal classification depends on their exact features and underlying model. The most prominent stable coins, such as USDT and USDC, are based on an IOU model. Each token is backed by one USD.[5] As a result, they are likely to fall under the definition of currency denominated assets and are thus excluded from the definition of crypto assets under the PSA. For more information on the classification of different stable coins, click here.

cTokens represent a user’s balance in the Compound protocol. As the market earns interest, the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying assets. This raises questions as to whether cTokens represent beneficiary certificates in a money market fund (MMF) or interests in a collective investment scheme and therefore constitute electronically recorded transfer rights.

Beneficiary Certificates in an MMF

Traditionally MMFs are used as cash management vehicles for retail and institutional investors. Defining features are the payment of dividends, the fact that investors can redeem their certificates at any time, and the fact that MMFs seek to maintain a stable net asset value. The redemption of a substantial amount of beneficiary certificates may, however, result in a loss of liquidity and negatively affect the remaining certificates’ price.

The risk of illiquidity also exists in the case of Compound and other DeFi protocols. As the following graphic shows, it may be even more pronounced than for traditional MMFs.

The difference between Compound and traditional MMFs is that a user’s yield is independent of profits generated by the protocol. Rather than calculating the yield after repayment of the borrowed loans, the protocol uses the prevailing interest rate for each interval when calculating the compound interest rate. Whether a loan is fully paid back at any point in time or not, is irrelevant

It is further worth noting that the Compound protocol does not constitute a legal entity that could act as a trust. The protocol is also not controlled by a legal entity that may otherwise be seen as a principal.

Interests in a Collective Investment Scheme

The definition of collective investment schemes in the FIEA[7] is intentionally broad and covers various arrangements that are used to pool money for investment purposes. Investors in a collective investment scheme are entitled to participate in the earnings a scheme generates but bear a business risk at the same time. If the scheme suffers a loss, investors in the scheme suffer a loss as well.

The argument that Compound and other DeFi platforms do not pay dividends can also be used with regard to collective investment schemes. Unlike investors in a collective investment scheme, holders of cTokens earn a yield irrespective of profits generated by the platform. The yield solely depends on the accrued interests over time and is calculated by using the interest rate on the respective markets for each block.

While there is an illiquidity risk, lenders should generally not make a loss when using Compound. This is due to the over-collateralization and auto-liquidation of loans where the balance of the collateral is insufficient to support the loan. If this promise holds true, the situation is fundamentally different from collective investment schemes where investors may actually suffer a loss.

It may further be argued that cTokens do not fall under the definition of interests in a collective investment scheme as they do not represent rights. Rights, by definition, require a counterparty. In the case of DeFi, a counterparty does not exist. Instead, assets are collected and distributed via smart contracts according to predefined rules on a factual basis. Whether the regulator will follow this argument remains to be seen. Yet, we believe that there is plenty of room to argue that cTokens and similar arrangements do not fall under the definition of collective investment schemes and do, therefore, not constitute electronically recorded transfer rights under the FIEA.

Type II Crypto Assets

Since cTokens can be transferred electronically and exchanged with other tokens, they represent type II crypto assets under the PSA. The fact that the tokens become convertible into an increasing amount of the underlying asset does not lead to different results. This is because their value is only driven by market forces, namely supply and demand. The protocol merely ensures that the value of cTokens does not decrease relative to the underlying asset over time.

Governance tokens issued by the Compound protocol constitute type II crypto assets. They can be exchanged with other crypto assets but are not used for payment. The fact that governance tokens provide the user with voting rights is irrelevant for the legal classification in the absence of other features.

The lending and borrowing of crypto assets are not regulated under Japanese laws. A banking license or money lending license is therefore not required.

The exchange of crypto assets is generally considered a crypto asset exchange business in Japan. This applies irrespective of whether the exchange is facilitated by a centralized exchange, a decentralized exchange (DEX),or another smart contract if there is a controller.

Whether the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA is not clear. Neither the PSA nor any subsidiary legislation contains a definition of exchange. Yet, there are good reasons to doubt that the issuance of cTokens in exchange for the supply of other tokens constitutes an exchange within the meaning of the PSA and must, therefore, be registered with the Financial Services Agency (FSA).

cTokens are issued when a user supplies other tokens to the protocol. While this might look typical exchange of crypto assets, there is a fundamental difference. The user does not lose control over the initial amount deposited. cTokens more or less serve as a key to unlock the initial amount deposit and can be used at any time to do so – provided of course, there is sufficient liquidity. For typical exchanges, this possibility does not exist. The same applies to the exchange of cTokens for other crypto assets.

The issuance of governance tokens is not an exchange business as well. While the issuance of tokens in exchange for liquidity, is sometimes compared with ICOs the key difference is that there is no payment of consideration for receiving the tokens. Instead, the tokens are issued as a subsidy by the platform without additional consideration. It is therefore more akin to an airdrop where an issuer aims to promote his platform. Also, in these cases, it is not necessary to register as a crypto asset exchange.

The definition of crypto asset exchange services also includes custody business. When tokens are locked into a smart contract, this may generally be considered custody under the PSA. It may however be argued that this does not apply where the smart contract creator does not have control over the contract. In these cases, only the user is able to unlock the supplied amount by transferring cTokens to the smart contract and to release the funds. The automatic liquidation function does not change this result as the protocol creator does not have control over the funds at any point of time.

While DeFi has become increasingly popular over the last few months, it has not been on the radar of Japanese regulators so far. The good news is that certain protocols and tokens will most likely not fall under the FIEA. This will hopefully allow DeFi to get some more traction on the Japanese market and allow exchanges to add DeFi to their services.

As so often, the devil is in the detail. Much depends on the structure of the overall arrangement and the token design. Existing projects that intend to enter the Japanese market are therefore well advised to analyze their protocol and token design carefully.[8] The same applies to crypto asset exchanges that intend to add further services in the future to become more attractive in an increasingly competitive market.

We will analyze the possibilities resulting from DeFi and PoS for exchanges in our next article. Stay with us.

DISCLAIMER

The DeFi protocols mentioned in this article, in particular Compound, are used for illustrative purposes only. Given the format of the article, not all details of the protocol and token design have been considered comprehensively, so that the results of the assessment may deviate from the results by the regulator or a legal opinion prepared for the respective project. By no means, the explanations should be understood as a legal opinion regarding DeFi protocols mentioned in this article.

[1] According to DeFi Pulse, 28.03 percent of the USD 2.51 billion total value locked in DeFI is currently locked in Compound, DeFi Pulse, retrieved from https://defipulse.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[2] Compound, retrieved from https://compound.finance/ctokens (accessed on 10 July 2020).

[3] It is worth noting that a user’s collateral would immediately be liquidated to a certain extent with the first interest payment becoming due.

[4] For this paper, utility tokens are understood as tokens that give token holders access to an application or a service and which serve as a platform-internal currency.

[5] For USDT, the accounts have not been properly audited so far.

[6] Alethic, Illiquidity and Bank Run Risk in DeFi, retrieved from https://medium.com/alethio/overlooked-risk-illiquidity-and-bank-runs-on-compound-finance-5d6fc3922d0d (accessed 10 July 2020).

[7] Article 2(2)(v) FIEA.

[8] DeFi, by definition, does not necessarily involve a central entity controlling the project. It may, therefore, be difficult for the regulator to get hold of the persons behind the project. If a project aims to get more traction in the regulated space, there is however no way to cut some corners or to circumvent regulation altogether.

| fund type | examples | type of securities under the FIEA | securities registration requirements for public offerings | disclosure requirements | |

| self-offering | third-party offering | ||||

| corporation | investment corporations (domestic) | type I | not possible | type I FIBO | yes, for funds investing >50 percent in securities (exemptions in case of private placements) |

| investment corporations (foreign) | type I | not possible | type I FIBO | ||

| KK | type I | no registration | type I FIBO | ||

| GK | type II | no registration | type II FIBO | ||

| trust | unit trusts (domestic) | type I | type II FIBO | type I FIBO | |

| unit trusts (foreign) | type I | type II FIBO | type I FIBO | ||

| partnership | partnerships under the Civil Code | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | |

| silent partnerships under the Commercial Code | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

| limited partnerships for investment under the Limited Partnership Act for Investment | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

| limited liability partnership under the Limited Liability Partnership | type II | type II FIBO | type II FIBO | ||

Where interests in a fund are offered by the fund itself to Qualified Institutional Investors (QII) only, the fund does not have to register as a Financial Instruments Business Operator (FIBO) and may instead submit a comparably simply notification to the Financial Services Agency (FSA) – so-called Article 63 exemption. This exemption applies only in case of self-offerings. Thirds parties distributing units or interests in a fund are not covered by the exemption and must register as a FIBO.

You will find more information on the regulatory environment for partnership-type funds and the Article 63 exemption in our article on funds regulations in Japan.